To address the water needs of a growing population amid shortages, the Colorado Water Plan in 2015 set a goal of attaining 400,000 acre-feet of new water storage by 2050.

Colorado is working its way toward that goal, but building new storage is easier said than done. Increasing environmental and social concerns, limited geographic locations, and even more limited water rights have made many traditional reservoir storage projects tougher to build. On top of that, long-range forecasting — to figure out how much water is going to be available to be stored — has become especially difficult as a result of climate change.

An April 2020 study published in the journal Science found that the American West’s current drought is as bad or worse than any in the past 1,200 years of tree-ring records. Ordinarily, storage would be the obvious solution to drought and dry years. You collect moisture in wet years and save it for times of need. But climate change has created a catch-22. Storage may be necessary, but it has become more challenging to build and less water is available to capture.

Dan Luecke, former director of the Environmental Defense Fund’s Rocky Mountain office, says these challenges have upended a philosophy long built on risk analysis to one defined by “decision-making under uncertainty.”

“For a long time, we’ve known there’s risk but we could look to the historical record to manage it,” says Luecke. (Luecke also serves on the Water Education Colorado Board of Trustees). “With climate change, that record is called into question … The nature of the game has changed.”

The cascading challenges of climate change have led water managers to think creatively about alternatives to traditional infrastructure. Greeley, for example, replaced a plan to expand an existing reservoir with one that will store water underground. Front Range districts collaborated to reallocate the space in Chatfield Reservoir, a flood storage basin, raising the water level to add permanent water storage supply. As part of the Basin Implementation Plan for the Yampa/White/Green River Basin, water managers are exploring putting reservoirs high in the mountains to limit evaporative loss.

Decision-making under uncertainty makes it all the more complicated for water providers to meet Colorado’s water needs and has caused many to reexamine what a smart storage project is made of — one that can help meet water supply goals for many water users while respecting the environment, one that is also acceptable to stakeholders, and one with minimum impacts so that it can make its way through the permitting process. Water managers are growing increasingly innovative, out of necessity, to develop water storage projects that will work.

Reservoirs under Climate Change

It’s not simply a matter of how much water is available to store. Everything from the location and size of reservoirs to the timing for capturing runoff and for making releases is being reviewed. Various climate models, including those used by the Colorado Water Conservation Board for state water planning, project warmer temperatures that will affect evaporation rates in rivers and reservoirs and seasonal shifts in precipitation, including reduced mountain snowpack and earlier runoff. Earlier and reduced flows could, for instance, necessitate dams releasing water earlier to meet demand.

Temperature rise, too, makes storing water a challenge. Any pool will lose water through evaporation, and more during hot, dry times, but the loss is worse for reservoirs at lower elevations with more exposed surface area. The science used to estimate evaporative loss is imprecise — estimates could be off by as much as 20 to 30 percent, according to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, which is conducting a study to refine its methods. Even so, a 2018 Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society study estimated that losses from Lake Powell and Lake Mead could total as much as 15% of the annual upper basin allocation among Colorado River Basin states, or five to six times the annual water use of Denver. The same study said that summer evaporation rates may have risen by as much as 6% over the last 25 years.

The National Climate Assessment, published in 2018, states that climate change is fueling stronger storms that could overwhelm dams and infrastructure designed to capture more moderate storm surge flows. It’s also intensifying wildfires that destroy landscapes, load reservoirs with sediment, and threaten water delivery infrastructure.

The 2019 Technical Update to the Colorado Water Plan lays out a number of alternatives to new traditional storage projects, including rehabilitating existing infrastructure, reallocating flood storage to active storage, and using below-ground aquifer storage alternatives. While the options are vast, the update says that to meet the state’s goals, “at least some new large reservoirs are needed.”

But building those reservoirs also requires water to fill them, says Brad Udall, senior water and climate research scientist at Colorado State University. Water rights are not as easy to come by in an era of constraint. Any new water rights claimed today are junior in the state’s legal priority system, making storage necessary to capture peak flows after all senior water rights are satisfied. But as climate change shifts the timing and magnitude of peak flows, reservoirs may not be as effective a tool for managing junior water rights.

“A dam is a bit like opening a bank account, there has to be something to put in it,” Udall says. “Ultimately, everything bends to the hydrological realities of what the supply is.”

The Jigsaw Puzzle

The era of uncertainty doesn’t just make individual storage projects a puzzle — the long-range plans that help utilities figure out what storage they need are now a tangle of variables. Balancing climate-complicated precipitation projections with population and water use trends, regulatory changes, and competition for resources can make the standard planning process a head-spinning endeavor.

When Colorado Springs Utilities started updating its 2017 Integrated Water Resource Plan (IWRP), the utility wanted a “comprehensive view” that would take a hard look at risk analysis, says water planner Kevin Lusk. Colorado Springs doesn’t sit on a major river system and relies on storage in remote watersheds to manage its variable supply. In the early 2000s, the utility’s water yield saw a 600% difference between the driest and wettest years.

Realizing that a backward-looking dataset might no longer apply to a present and future defined by climate change, the utility took a state-of-the-art new approach to its planning process. Recently, Colorado Springs partnered with the consulting firm Black and Veatch, which expanded the multi-objective evolutionary algorithm (MOEA) to utilities to help them assess the complexities in planning. The machine learning tool can project thousands of possible futures using precipitation, temperature and hydrological factors, then help planners narrow down their range of possible options.

“As these plans get so big, it’s hard for the human mind to comprehend them,” says Leon Basdekas, a private consultant who worked at Colorado Springs Utilities, then Black and Veatch, designing and managing the utility’s IWRP. “This tool allows you to evaluate complex planning options in ways that would be impossible to do otherwise.”

Leon Basdekas, pictured beside Monument Creek, worked with Colorado Springs Utilities using a machine learning tool to help the water provider assess complex future water supply and demand scenarios and evaluate where new water storage could be beneficial. Photo by Matthew Staver

For Colorado Springs, the advanced IWRP process helped water planners see a range of climate and streamflow possibilities, then identify 14 storage options that could meet future water demand. Some, like a potential new reservoir on Williams Creek or one upstream of Rampart Reservoir, have been under discussion for years. Others are more general concepts without specific sites, such as gravel pit storage along the Arkansas River. Among those identified projects, Colorado Springs has also been exploring Eagle River storage options, including the potential Whitney Reservoir, to collect and store Western Slope water, although nearby towns and others have objected to possible impacts on the Holy Cross Wilderness Area. Lusk says Whitney Creek alternatives are “one of many possibilities” and that the IWRP analysis even considers “less tangible characteristics” like community values and opposition to any individual project when optimizing storage opportunities.

More than anything, Lusk says, the advanced modeling helped the utility gain a better appreciation for the full scope of storage and transmission. The “a-ha moment,” he says, is seeing how one individual new reservoir may not mean as much for the system as, say, shoring up existing pipelines to make the already-built system run more efficiently.

“We can’t just look at storage on its own, it’s a package deal with supply and conveyance,” Lusk says. “This is a complex jigsaw puzzle.”

When Mitigation Meets Enhancement

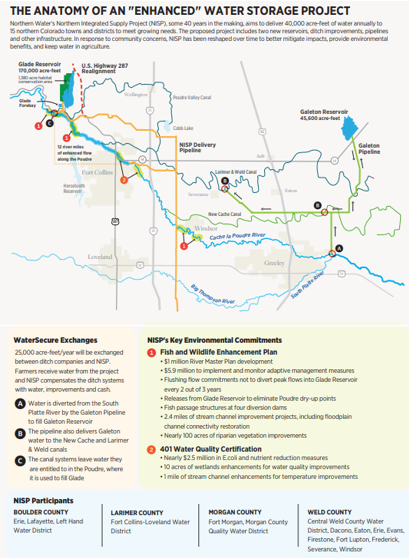

To the north, the Northern Integrated Supply Project, or NISP, has been moving through a decades-long process to obtain the necessary permits and to gain the favor of local stakeholders. NISP has been reshaped, with operational changes and environmental improvements now built in, in response to stakeholder concerns.

Northern Water’s project, if fully approved, will build two reservoirs, one northwest of Fort Collins off the Cache la Poudre River and another northeast of Greeley, to deliver nearly 40,000 acre-feet of water a year to 15 communities and irrigators along the Front Range. With the population of northern Colorado expected to double by 2050, backers say that such a large shared storage project is necessary to efficiently serve booming towns like Erie, Windsor and Severance. Through water exchanges with farmers — which will average about 25,000 acre-feet per year — and the purchase of conservation easements on farms, Northern Water says the project will also help farmers reduce the negative impacts of buy and dry by keeping water on farms while serving the growing Front Range population.

But supplying those growing towns will necessarily require impacts. NISP will involve constructing the 170,000 acre-foot Glade Reservoir (to accommodate the reservoir, seven miles of U.S. Highway 287 will be relocated) and the 45,600 acre-foot Galeton Reservoir. Northern Water will also build another forebay reservoir, five pump plants, and 80 miles of pipeline.

That kind of construction naturally attracted opposition from environmentalists and some communities. Concerns include that taking water out of the already-stressed Poudre River could reduce its crucial spring peak flows, which flush sediment downriver and restore habitat.

Several environmental reviews as part of the permitting process concluded that the need for storage was there, even after accounting for planned water conservation savings. With so many communities involved, scrapping the collaborative project, as some environmental groups advocated for, would leave them all competing for limited resources.

“I think quite a few participants who saw [NISP] as a [potential] future supply are now looking at this as the future,” says Christopher Smith, general manager of the Left Hand Water District and chairman of the NISP participants committee. “I don’t think anyone is left who is speculating on this. It’s necessary.”

So Northern Water started looking for what project manager Carl Brouwer calls “the wow factor.”

“We really changed our perspective to thinking about how we could put water back and be a part of the preservation of the Poudre River,” Brouwer says.

The Cache la Poudre River through Fort Collins encounters many small diversions and has historically faced dry-up points. Through the Northern Integrated Supply Project (NISP), Northern Water, though diverting water upstream, has committed to stream-channel improvements and revegetation, E. coli and nutrient reduction measures, year-round streamflows, and more. Photo by Flickr user JeffreyJDavis

Project proponents added an estimated $60 million in mitigation and enhancement measures, bringing the total estimated project cost to about $1.1 billion. The idea is that water would be released from Glade Reservoir year round and no water will be diverted to storage when flows dip below 50 cubic feet per second (cfs) in the summer and 25 cfs in the winter to eliminate spots where the river already dries up. Collection operations will be adjusted to keep peak flows in the Poudre River two out of every three years, and 90% of the time little or no diversion will take place during peak flows. Organizers will also build new fish passage structures and improve 2.4 miles of stream channel near a Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW) fish hatchery north of Fort Collins.

The mitigation and enhancement plan received unanimous approval from CPW and the Colorado Water Conservation Board in 2017, and the Colorado Water Quality Control Division approved the project’s 401 Water Quality Certification in 2020. NISP has continued moving through the federal permitting process, with final approval expected this spring or summer.

Karlyn Armstrong, water project mitigation coordinator for CPW, says that the flow program will be a benefit to the river. “Currently the river goes dry in places — once the program comes online, the river will have water 365 days a year through the conveyance flow reach,” Armstrong says. “Aquatic life will benefit from sustained minimum flows.”

Critics remain. In August 2020, the Fort Collins City Council voted 5-1 to oppose the project, citing the potential loss of spring flows, and some environmentalists say communities should explore options with less of an environmental footprint.

But Brouwer says that the project, combined with Northern’s efforts on conservation and water exchanges, should set the new standard for infrastructure in the state with its environmental focus.

“What really changed was embracing the enhancement part of mitigation and enhancement. We can make it better,” Brouwer says. “We’ve set the bar pretty high and I do think this will become the norm.”

Addressing Demand

Improved or not, some still say a large storage project like NISP shouldn’t happen at all. Boulder-based Western Resource Advocates has been a long-time opponent of NISP and in 2012 released an alternative plan it said could meet the needs of Front Range communities without the footprint of new infrastructure. The nonprofit’s “Better Future” alternative included conservation tools that would offset 20,482 acre-feet of use by 2060 and apply reuse technology to another 4,905 acre-feet. Combined with flexible water sharing agreements between agricultural users and municipalities and more thoughtful expansion onto previously irrigated agricultural land that could come with water rights, WRA says their plan reimagines what adding supply could look like.

“We know we need more storage going forward, but new storage doesn’t have to be connected to new development,” says Laura Belanger, water resources engineer at Western Resource Advocates. “Alternative supply portfolios that include reuse or conservation can mean storage that optimizes existing supplies more efficiently.”

WRA’s plan as an alternative to NISP was rejected in 2018, as were all other alternatives proposed during the public comment period, when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers issued NISP’s Environmental Impact Statement, saying that these options “did not meet the project’s purpose and need and practicability screening criteria.” WRA says it relies on different calculations than the economic reports backing NISP and has continued to update its alternative in a series of recent comments on the NISP proposal.

Whether or not it could replace NISP, the “Better Future” model represents how some are thinking about limiting demand as a way to reduce the need for additional storage. Aggressive conservation has started to decouple water use from population growth in some cities across the West; a survey of 20 Western cities published in the journal Water found that between 2000 and 2015, total water use dropped 19% while populations increased by 21% on average. Denver Water has reduced per capita water use by 22% over the past decade.

The City of Aurora has also made conservation and reuse a foundational part of its water plan, including more efficient landscaping requirements, rebates for low water-use appliances, and requirements that new developers make their buildings less wasteful. Tim York, the city’s water conservation supervisor, estimates that it costs about $5,187 for each acre-foot of water conserved, compared to about $25,000 per acre-foot for water acquired on the open market.

That doesn’t mean Aurora isn’t looking for more storage. The city is moving ahead on the proposed Wild Horse Reservoir project, a 96,000 acre-foot storage site in Park County.

“There’s always going to be more to be done from conservation and efficiency. At the same time, you can only get so low,” says York. “You get to a point where you need storage. The mindset that you can conserve your way out of any drought is just not realistic.”

Many small- and medium-sized utilities don’t have the staff to mirror Aurora’s efforts, but Belanger says that the strain on resources under the drought makes it necessary for all municipalities to embrace conservation.

“The more efficient existing and new development is, the more water you can have in the supply,” Belanger says. “Managing the demands of your community produces sustainable savings.”

Can Restoration Double As Storage?

Some advocates say it’s time to think beyond cement and instead embrace natural watershed restoration as a storage solution.

In its 2016 Water Plan, the State of California declared that source watersheds would be considered “integral components of water infrastructure,” putting reviving watersheds on essentially the same level as building new dams or pipelines. While Colorado hasn’t adopted similar language yet (Montana is the only other state to do so), there is increased attention to restoring watersheds as an ecological tool with water storage benefits.

“Our water has so much to do, we should give it a longer reach and take advantage of all the benefits,” says Abby Burk of the Audubon Society. “When water is in rivers instead of sitting in reservoirs, there are so many more benefits that support healthy, thriving ecosystems.”

Snowmelt and storm events, for instance, flash quickly through incised streams that are disconnected from their floodplains. Healthier connected floodplain-riparian areas can restore plant life, recharge underground aquifers, preserve flows for aquatic species, and even reduce flood risk. Water in the ground also won’t evaporate like it does from reservoirs. However, it’s less clear if this restoration work can provide the kind of material storage benefits providers want to see.

“We’re careful about saying that restoration of floodplains and wetlands does not produce more water, but it can change the timing,” says Jackie Corday, a consultant working with American Rivers on healthy headwaters issues. “The water can be attenuated [by absorption into the restored floodplain], the runoff is slowed when it’s stored as groundwater, then it slowly gets released throughout the summer instead of all at once.”

A series of beaver dams span much of the Middle Fork of the South Platte River in the Placer Valley, pooling water and spreading the river’s flows. Beaver systems like these store water and provide refuge for other species, even during low flow and drought conditions. Photo courtesy EcoMetrics

Stretching natural runoff releases into the hot summer months could help farmers irrigate for longer growing seasons without storing water above ground, but little research has quantified that potential. Researchers are eyeing projects meant to mimic beaver structures to see how they change flows. A project that’s currently underway to restore floodplains and wetlands upstream of Grand County’s Shadow Mountain Reservoir could offer a good model; preliminary assessments from that project are expected by the end of the year.

According to Melinda Kassen, senior counsel for the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership, restoration fits into a more natural philosophy of water systems. She hopes to see more municipalities begin to view natural infrastructure as just as valid as traditional infrastructure.

“You just have to remember that there is an alternative, and sometimes that’s hard when you’ve done something one way for 150 years,” Kassen says. “When we talk about water storage now, one of the first things we say is that we should be looking at green infrastructure instead of gray.”

Thinking System-Wide

A bigger way of thinking is taking hold in the South Platte River Basin, home to approximately 70% of the state’s population and its largest projected water supply gap. The South Platte Basin Implementation Plan, completed in 2015 to inform the state water plan, showed that, with a population expected to reach 6 million by 2050, there could be a maximum annual water supply gap of 540,000 acre-feet.

The “status quo” strategy to fill that gap for cities is buy and dry, says Joe Frank, general manager of the Lower South Platte Water Conservancy District in northeastern Colorado. Frank has always worked on behalf of the water users in his district, but as water stresses increase, he is thinking more creatively about the future of agriculture by “providing water security for both” farms and cities.

There are more water rights on the South Platte River than there is water to fulfill them in most years, which is why buy and dry — where cities purchase senior agricultural water rights, drying up a farm and gaining the priority to divert that water when flows are low — has been attractive to municipalities. As an alternative, new storage might help. Some flows are available for capture, just not every year. The South Platte Storage Study, ordered by the Colorado Legislature in 2016 and completed in 2017, found that while flows were extremely variable between 1996 and 2015, a median flow of 293,000 acre-feet per year in excess of South Platte River interstate compact obligations crossed the state line into Nebraska. The amount of water that could be put to use in Colorado is much less, the study found, but additional South Platte storage could help with a variety of things — from compact compliance to water sharing agreements to river flows and to better utilizing reusable return flows from upstream municipalities. It also found that a combination of storage pools working conjunctively up and down the river could be more beneficial than individual reservoirs.

To explore ways to move beyond individual reservoirs to close the gap, Frank and other water managers throughout the basin are collaborating on the South Platte Regional Opportunities Water Group, or SPROWG, and working toward a system-wide approach to storage and water use.

In a feasibility study published in March 2020, SPROWG members identified four alternative concepts that could help close the supply gap without diverting additional water from the Western Slope or buying up valuable water rights from local farmers. The study analyzed the potential to store between 215,000 and 409,000 acre-feet of water in various generalized locations between Denver and the Nebraska state line. New storage would rely on available flows not obligated to existing water rights, water that can be reused, or temporary lease agreements with farmers. Stored water would then be used locally, transported through a pipeline for regional use, or exchanged between locations.

The idea, said SPROWG advisory committee member Lisa Darling, was to think regionally instead of by district, to move water where it’s needed at any given time.

“Maybe there was this sort of older water buffalo thinking in the past, but I think we know now that we can’t develop projects in a vacuum anymore,” says Darling, the executive director of the South Metro Water Supply Authority. (Darling also serves as president of Water Education Colorado’s Board of Trustees.) “There’s a holistic system and that’s the prism we have to look through now.”

Dan Luecke, who fought multiple large infrastructure projects across the state, says he’s been encouraged by an increase in innovation where cities and growers are thinking more collaboratively on both storage and use. In an era of constraints, he says, it will take all users — even those across state lines — working together to think about creative and efficient approaches to the storage dilemma.

“If we could get cities and irrigators to agree to some kind of combined management scheme, we might need more storage but we could look at it in a more integrated and efficient context,” Luecke says. “It’s not about storage for this user or that area, it’s about an entire system that’s more flexible.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article stated that Aurora Water estimates that it costs about $600 in staff time and resources for each acre-foot of water conserved, but Aurora’s latest annual report estimates a cost of $5,187 per acre-foot of conserved water.

Jason Plautz is a journalist based in Denver specializing in environmental policy. His writing has appeared in High Country News, Reveal, HuffPost, National Journal, and Undark, among other outlets.

Print

Print