If your holiday wish is a small fix for climate change wrapped with a bow, one that comes with a modicum of good will, Chris Caskey may have what you’re looking for.

Caskey, 33, aims to capture the plumes of methane escaping from once-active coal mines near Delta and Somerset on Colorado’s West Slope to power and resurrect an old brick company.

If successful, Caskey’s endeavor will harvest sediment that is now choking Paonia Reservoir, using clay derived from that sediment to make pavers and bricks for landscaping. The process will free up more space for water storage and pull millions of cubic feet of methane—the most potent greenhouse gas—out of the atmosphere.

And if it’s really successful, the process could be replicated across the American West, where hundreds of reservoirs face sediment problems and coal-mine methane also escapes.

Caskey incorporated Delta Brick and Climate, a nod to the now defunct Delta Brick Company, in July. The former lecturer at the Colorado School of Mines has a Ph.D. in chemistry and materials science with additional expertise in energy.

Chris Caskey, founder of Delta Brick and Climate.

But he isn’t in this alone.

It was while hiking in Gunnison County that he was introduced to locals who were looking for ways to solve a methane problem.

It all began in 2017 when one of the last active coal mines in the region, West Elk, notified county commissioners that it wanted to expand. Commissioners asked for and were able to create the North Fork Coal Mine Methane Working Group. It included mine owners and managers, conservationists, scientists, county commissioners, and a few water officials.

The early days were tense, said Gunnison County Commissioner John Messner.

“Anytime you bring diverse interests together, especially folks that have had a pretty tough relationship, like coal mine owners and environmental groups, it can be hard. Just building a level of trust took a lot of time.”

Coal mines, already under the gun because of weak market conditions, were now being pressured to reduce methane emissions. With some money from the federal government and with the counties’ and West Elk pitching in, the working group began meeting.

But it was awkward.

“At the first meeting, almost no one talked,” Caskey said.

Eventually, though, they were able to begin brainstorming, while Caskey began researching ideas.

They examined whether to make fertilizer, plastics or electricity. None panned out.

Simply burning off the methane, however, proved to be a very lucrative proposal. Burning the gas turns it into carbon dioxide, another greenhouse gas, but one which is much less harmful than methane.

By lighting the gas on fire, Delta Climate and Brick could generate carbon credits, which can be sold in California’s carbon market. This would generate roughly $11 million a year in revenue, according to Caskey’s financial projections.

“There’s a reasonable business case for it,” he said.

And there is some irony attached to the process, he said. “This is the only time you’ll hear a conservationist like me say, ‘Let’s get a big machine up on the mountain and light something on fire.’”

Still Caskey thought there should be another way to use the leaking methane. He began researching high heat industries, such as ceramic and brick manufacturing.

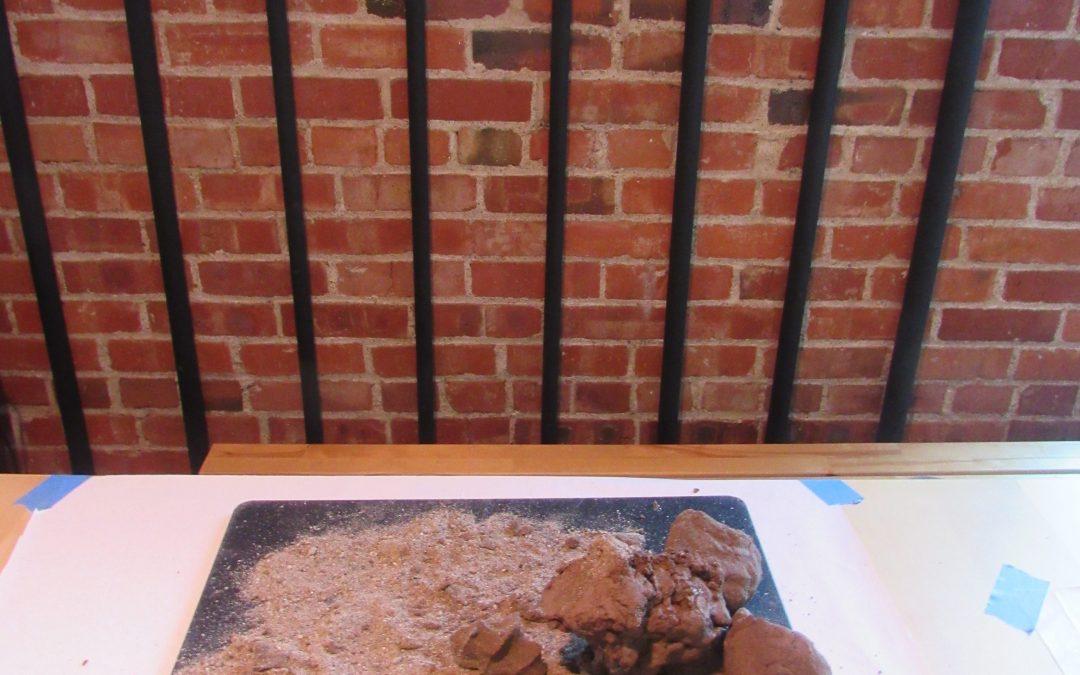

A sample paving stone from Delta Brick and Climate.

From the working group he knew that Paonia Reservoir was filling up with sand and losing storage space each growing season as a result.

Built in 1962 by the U. S. Bureau of Reclamation, the reservoir lies within Paonia State Park and is managed and operated by the Fire Mountain Canal Company. Its waters irrigate the hay meadows as well as the apple, apricot and cherry orchards of the scenic North Fork Valley.

Farmers there need every drop of water they can get. The reservoir diverts water from the sediment-heavy Muddy Creek. Growers have lost roughly 3,000 acre-feet of storage due to sedimentation, and that loss grows every year, according to Steve Fletcher, who oversees the irrigation system, reservoir and dam for the Fire Mountain Canal Company.

Fletcher allowed Caskey to begin sampling the sediment. It seemed promising. Then Caskey discovered the National Brick Research Center in Anderson, S.C., and a passionate, eccentric group of scientists.

Within weeks, he boarded an airplane with a bag of mud in hand and headed east to the research center. “They fired the bricks. Then they licked them, because they’re weirdos, and then they said, ‘It looks good. You can make high-quality products out of this material,’” Caskey said.

It was great news.

Back in Colorado, using grants from the counties and several state agencies, Caskey went through a six-month business incubator, researching the market for bricks. He burned through spreadsheets, crunching numbers to find the scale at which the born-again brick factory could be profitable.

It would need to be sited near a coal mine, to eliminate the high costs of piping gas long distances, and it would need to be reasonably close to the sediment source, again to eliminate transportation costs.

With key questions answered, Caskey and the working group are pushing forward.

In 2019, if all goes well, he will relocate to Paonia from Denver. He’ll rent a warehouse from one of the coal companies, installing a kiln and methane-capture system to create a pilot factory.

And he will tackle the other challenges that lie ahead. He’ll need permits from multiple state and federal agencies. He’ll need to secure access through Paonia State Park to the reservoir site. He’ll have to build a road.

And he’ll have to raise big-time cash, close to $1 million. That’s enough to hire a small staff, build a methane-capture system, harvest sediment, and make 1,000 bricks a day.

No private investors or venture funds have signed on to the project yet. But Caskey has received roughly $30,000 in grant money and he’s applied for numerous additional research grants from state and federal agencies who are interested in funding work to mitigate climate change.

“It’s an interesting opportunity,” Messner said.

And unlike a year ago, it has broad-based support. Mike Ludlow is president of Oxbow Mine in Somerset and a member of the working group.

Quick to point out that the amount of methane released by the mines is small in comparison to the ambient levels already present in the atmosphere, Ludlow nonetheless is supportive of Caskey and the working group.

“Controlling these emissions is in everyone’s best interest,” he said.

For Steve Fletcher, the prospect of finding even a partial solution to Paonia Reservoir’s sediment problem is alluring.

“Using the vented gas and then the sedimentation, you have a win-win on both sides and you’re making a product that is good for the environment. That is important,” Fletcher said.

Caskey is among a growing group of entrepreneurs worldwide who are pursuing market-based solutions to climate change. Susan Nedell is the Rocky Mountain representative for E2, a national network of environmental entrepreneurs with roughly 1,000 members.

“Almost everywhere you turn, people are looking for solutions to climate change,” Nedell said. “This is a great solution.”

Ultimately, Caskey knows that resurrecting this brick factory is only a small piece of the global puzzle. And that’s okay with him.

“The scale of the climate challenges are such that this is going to be only part of the solution, but it’s so much better than if we did nothing at all,” he said.

Jerd Smith is editor of Fresh Water News. She can be reached at 720-398-6474, via email at jerd@wateredco.org or @jerd_smith.

Fresh Water News is an independent, non-partisan news initiative of Water Education Colorado. WEco is funded by multiple donors. Our editorial policy and donor list can be viewed here.

Print

Print