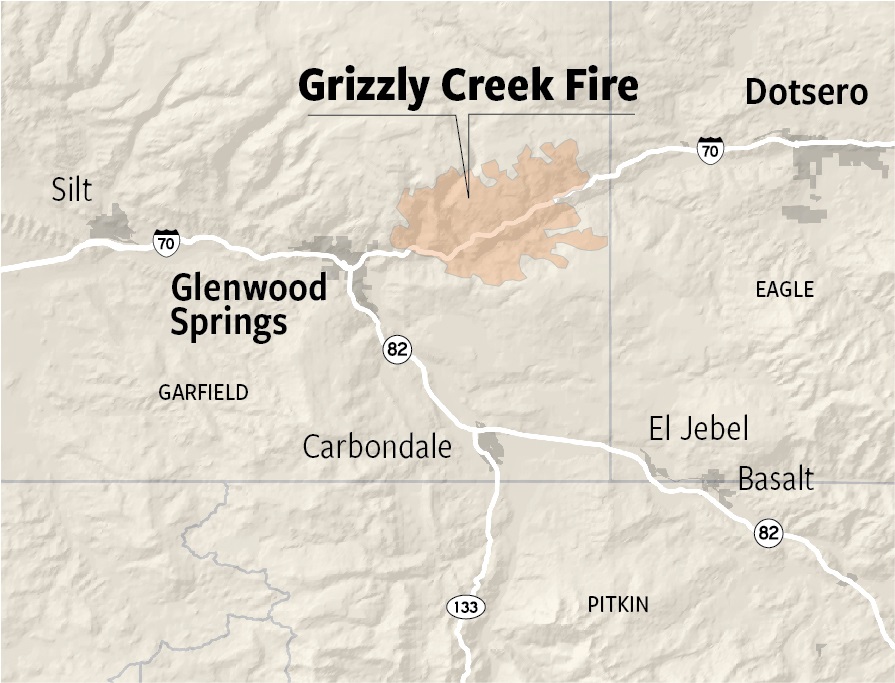

Liz Roberts is digging into snow-soaked dirt just above the banks of Grizzly Creek in western Colorado. With bare fingers she sifts through the dark soil, looking for life amid the ruins of last summer’s devastating Grizzly Creek fire.

When she finds tiny dormant roots, she smiles and exposes more soil to show visitors that this ground, just two or three inches down, is filled with plant matter that will grow and bloom in the summer when the snow melts.

But farther along this same trail, in the White River National Forest just east of Glenwood Springs, there is thick ash beneath the snow, and few dormant roots. This means the soil was so injured by the fire, which burned for more than four months, that it has become disconnected from the mountainside, and the ash lying unrooted above it will be carried into the creek this spring as the water melts.

In unburned forests, the spring snowmelt is a glorious, annual event.

But not this year.

Roberts and other forest experts know that the spring runoff will carry an array of frightening heavy metals and ash-laden sediment generated in the burned soils, posing danger to the people of Glenwood Springs, who rely on Grizzly Creek and its neighbor just to the west, No Name Creek, for drinking water.

Unseen toxins

Raging wildfires, like the massive burn that almost consumed Glenwood Springs last year, are easy to see. But what is rarely seen is the devastation to the natural mountain collection systems, where water starts as snow before melting in the spring and flowing down into creeks and eventually into water systems for towns and agricultural lands.

As soils burn, naturally occurring substances that would normally be locked in place are released.

“Sometimes we see lead, mercury, cadmium, possibly arsenic,” said Justin Anderson, Roberts’ colleague and a U.S. Forest Service hydrologist. “They can be dangerous, especially in high concentrations.”

Like other Western states, Colorado is in red alert mode this year, in part because these new megafires, triggered by drought and climate change, ravaged not just Glenwood Springs’ water system, but other major systems as well. Northern Water, for example, manages the Colorado Big-Thompson Project, which serves more than 1 million people and hundreds of farms on the northern Front Range and Eastern Plains. Burning at the same time as the Grizzly Creek fire, the Cameron Peak and East Troublesome fires rampaged through the project’s mountain collection system, affecting water supplies for Fort Collins, Greeley, Boulder, Broomfield and Loveland, among others.

Data Source: Rocky Mountain Area Coordination Center, Graphic by Chas Chamberlin

Even as communities across the state keep their eyes on a 2021 fire season expected to be as bad as that of 2020, when the state saw the largest fires in its history explode, they are racing to create high-tech water treatment programs capable of filtering out the toxins now present in their once-pristine water, and replacing the pipes, intake flumes and grates damaged beyond repair last year.

Esther Vincent, Northern Water’s director of environmental services, expects the agency to spend more than $100 million over the next three to five years, restoring hundreds of thousands of acres of forest in Rocky Mountain National Park, Grand County and along the Front Range in Boulder and Larimer counties. That is nearly triple the agency’s $40 million reserve fund.

Ravaged pipes, reservoirs

“Over half of our major watersheds were affected,” Vincent said. “In some of them 90 percent is burned. Because there is no option to bypass the runoff that is going to come into our system, it will enter our reservoirs and affect all of our infrastructure on the West Slope.”

Restoring forests is an undertaking that requires decades of work and whole new industries to execute effectively.

Mike Lester is Colorado State Forester. Thanks to Colorado’s rapid recovery from the Covid-19 budget crisis and federal relief funds expected later this year, his agency has more money than it’s ever had to help restore forests.

”We’re going to be pretty well supported this year,” Lester said. The state added $6 million this past year for restoration work and it is expecting another $8 million July 1, when the new fiscal year begins.

Colorado has some 24 million acres of forest, most of which is owned by the federal government, and to a lesser extent, private landowners. Roughly 10 percent of those acres are in need of immediate attention to protect towns and homes in the wildland urban interface, Lester said. Colorado’s wildland urban interface, also known as the WUI, has become increasingly populated, creating greater risk to lives and infrastructure and complicating forest management.

Loggers wanted

Repairing the forests, thinning trees so the fires don’t burn with such intensity, and stabilizing hundreds of thousands of scarred mountain slopes requires skilled personnel and methods for utilizing the downed timber.

“We’re way short of resources,” Lester said. “We don’t have a huge amount of logging and professional forestry in Colorado. There is only so much money you can spend well before you run into capacity issues.”

In the short-term communities are focused on doing what they can now to keep their water systems safe.

Matt Langhorst is Glenwood Springs’ director of public works. When the Grizzly Creek fire ignited last August, he could tell almost immediately that the flames were going to engulf the water system’s intake structures in the White River National Forest high above the town at the top of Grizzly and No Name creeks.

“The second I saw the smoke coming over the hill, I knew it was right around our two watersheds. I picked up the phone and called the fire department and said, ’We’re going to have a problem.’”

A massive loss

Nine months later, Langhorst and his crews have reworked the high mountain intake structures and they’ve finished a complete rebuild of the town’s small water treatment plant so that it can remove the pollutants expected to contaminate its once-clear waters, and filter out massive sediment loads that are already beginning to come down into the creeks as they enter the Colorado River just east of town along I-70.

“We are expecting it to change the water quality for three to seven years, but it could be longer than that,” Langhorst said. “It is a massive loss.”

And costly. Glenwood Springs Mayor Jonathan Godes said the work needed to repair and rebuild its water system, and create a safe evacuation route if Glenwood Canyon is shut down again as it was last summer, will likely cost three times its annual operating budget of $19 million.

“It’s something we can’t afford,” Godes said. “But we can’t afford not to do it.”

In response, state agencies are rethinking how they provide emergency funds as natural disasters such as these megafires happen more frequently.

Help, please

The Colorado Water Conservation Board (CWCB), last fall, was able to offer Glenwood Springs $8 million in a matter of days so that Langhorst and his crews could get into the high country to do critical construction work before winter snows arrived.

Kirk Russell oversees the CWCB’s loan funds. He said the agency was able to move quickly because it had seen the damage done and the loan delays that occurred after the state’s catastrophic floods of 2013. Back then, federal emergency funds took months to reach devastated Front Range communities and farm irrigation systems that were blown out by powerful flood waters.

“Fast forward to the wildfires that we saw last year and we foresaw there was going to be a need to respond quickly,” Russell said.

Now the agency has new emergency rules that provide for quick approvals on three-year, no-interest loans when water systems are harmed by wildfires.

“Do we need more money and more flexibility? Absolutely,” Russell said.

Crossing boundaries

The state also needs a more cohesive response to managing and restoring forests and the water systems embedded in them. Key to that effort is a two-year-old initiative called the Colorado Forest and Water Alliance, an advocacy group that includes federal and state forest officials, water utilities, logging industries and environmental groups.

Ellen Roberts, a former state lawmaker from Durango, has helped spearhead the fledgling effort and is working on other local initiatives designed to work effectively across city and county boundaries, as well as private, public and federal lands.

Colorado’s lawmakers and the federal government have pledged more than $20 million this year to quickly jumpstart the work.

“I am very encouraged by that,” Roberts said. “A good chunk of the money will need to go to immediate post-fire work, but we need to shift gears soon to put the money in at the front end [to thin the over-grown forests]. Hopefully we will be seeing both with the money that has been set aside. This is not a one-and-done investment. It has to be viewed as being chapter one of a very, very long book.”

Water comes down

Back out in the White River National Forest, the annual snowmelt above Grizzly and No Name creeks has begun.

Liz Roberts, an ecologist with the U.S. Forest Service, examining burned soils in the White River National Forest near Glenwood Springs. March 25, 2021. Credit: Dave Timko, This American Land

And Matt Langhorst is waiting, hoping that the residents of Glenwood Springs, who have enjoyed more than 115 years of clear mountain water, won’t notice any difference in how their water tastes.

He got hundreds of calls last August when the town was forced to shut off its fire-engulfed water system and use an emergency source temporarily.

Each call was roughly the same, he said.

“Everyone wanted to know, ‘What happened to my water?’”

Jerd Smith is editor of Fresh Water News. She can be reached at 720-398-6474, via email at jerd@wateredco.org or @jerd_smith.

Fresh Water News is an independent, nonpartisan news initiative of Water Education Colorado. WEco is funded by multiple donors. Our editorial policy and donor list can be viewed at wateredco.org.

Print

Print