Last year, in southwestern Colorado, the town of Cortez, population 8,000 give or take, had the rare distinction of representing the deepest, most alarming red spot on the U.S. Drought Monitor’s map.

It wasn’t a designation this farming and ranching community took much comfort in, according to Mike Preston, manager of the Dolores Water Conservancy District.

The San Juan/Dolores River Basin, which includes Cortez, that spring had a snowpack that registered just 51 percent of average, Preston said.

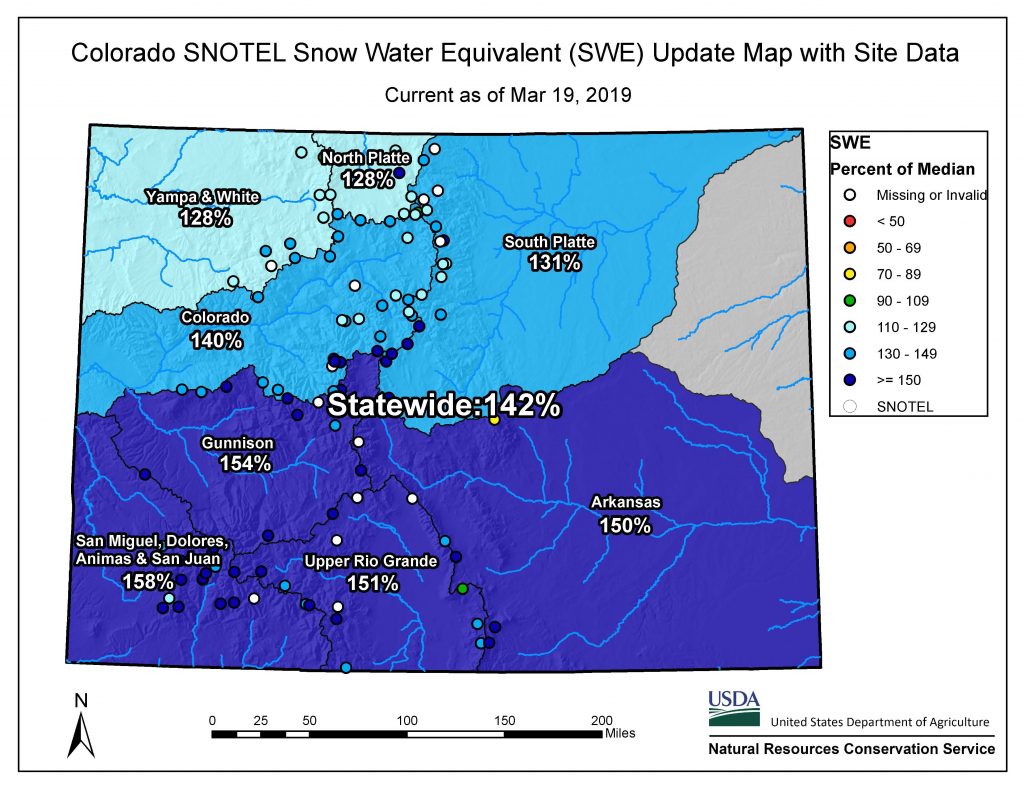

This spring, that number is 158 percent of average, three times higher, and that angry, painful deep red color has faded.

On the drought maps, it’s now an innocuous yellow, and a look at a snowpack map shows nothing but a soothing blue.

“We’re in substantially better shape,” Preston said.

Snowpack is a critical issue in Colorado because most of the state’s water, whether for communities, businesses or farms, derives from the snow that falls each winter.

Across the state snowpack has been skyrocketing, and while it has sent avalanche danger through the roof, it has also given cities, farmers, drought watchers and water districts a much-needed breather from an almost unbroken, 19-year run of drought.

As of March 19, statewide snowpack is roughly 142 percent of average, more than two times higher than it was last year at this time, when it stood at just 69 percent of average, according to Brian Domonkos, snow survey supervisor for the U.S. Natural Resources Conservation Service in Lakewood.

“Snowpack is gaining significantly and fast,” Domonkos said.

While last week’s blizzard helped parts of the state, it’s been the relentless nature of subsequent storms that has brought the numbers to these eye-popping levels, water officials said.

But snow isn’t water, and hydrologists and forecasters say they will be keeping a close eye on how quickly spring runoff occurs, how fast the weather heats up, and how much demand increases in the summer. All those factors will determine how much of the snow turns into water and makes its way into streams and reservoirs. Another key concern is how much water the state’s ultra-dry soils, still parched from last year, will absorb.

“We’re in the best shape we could have hoped for,” said Taryn Finnessey, chair of the state’s Water Availability Task Force and senior climate change specialist with the Colorado Water Conservation Board.

The lush, deep snow has already begun pulling Colorado out of drought, with small portions of the state – primarily along the southeastern border — finally free of the designation, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor.

Russ Schumacher, state climatologist and director of the Colorado Climate Center, said he expects more of the state to witness dramatic improvements.

Last October, after the third-driest year on record, almost every corner of Colorado was experiencing some level of drought, and 16 percent of the state was experiencing the worst category, known as exceptional drought. This month, however, that deep, dark red color that represents exceptional drought is gone.

“It’s a remarkable change over the past five months,” Schumacher said Tuesday at a meeting of the state’s Water Availability Task Force, which monitors drought and water conditions.

Scientists and hydrologists gathered for the meeting were shaking their heads and telling tales of double and triple checking the numbers to make sure they weren’t an apparition. In the Upper Colorado River Basin, for instance, the snowpack through March 18 is 300 percent of average. “The Upper Colorado is seeing one of the best years it’s ever had since we started measuring snowpack,” Domonkos said.

Reservoirs too are expected to benefit from the deep snow, with some systems, such as Denver Water’s, expected to come close to filling and others, such as Blue Mesa near Gunnison, expected to at least regain normal storage levels.

Across the seven-state Colorado River Basin, big snow has helped add water to lakes Powell and Mead, which have come dangerously close to reaching critical lows that would trigger water cutbacks in the next two years. Heather Patno, a hydrologist with the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, said the outlook for Lake Powell has brightened considerably. In February the forecast indicated the giant reservoir, which acts as a storage bank for the Upper Colorado Basin, would see just 64 percent of average inflows.

As of this week, however, that number has shot up to 102 percent of average. But Patno points out that the drought-stricken storage pool has a long way to go. “We’re still lower than we would like to be,” she said. “While this does give some relief to the system, it’s still important to realize that we’ve seen this before. One year of average conditions doesn’t mean we won’t see drought years in the future.”

At the end of the water year, this fall, Powell is still projected to be just 47 percent full.

As with all big snow years, however, the downside is flood risk, particularly in areas recently hit hard by wildfires, such as last year’s 416 Fire northeast of Durango and the Spring Fire, near La Veta Pass.

“Flooding is obviously a big concern,” Finnessey said.

Jerd Smith is editor of Fresh Water News. She can be reached at 720-398-6474, via email at jerd@wateredco.org or @jerd_smith.

Fresh Water News is an independent, non-partisan news initiative of Water Education Colorado. WEco is funded by multiple donors. Our editorial policy and donor list can be viewed here.

Print

Print