Biologist David Inouye spent part of his Tuesday afternoon harvesting Jerusalem artichokes from his garden in the 1,400-person town of Paonia in western Colorado.

“It’s been so warm and dry here that my garden’s ready to plant,” Inouye said. “I was actually thinking about maybe planting some spinach or peas this week.”

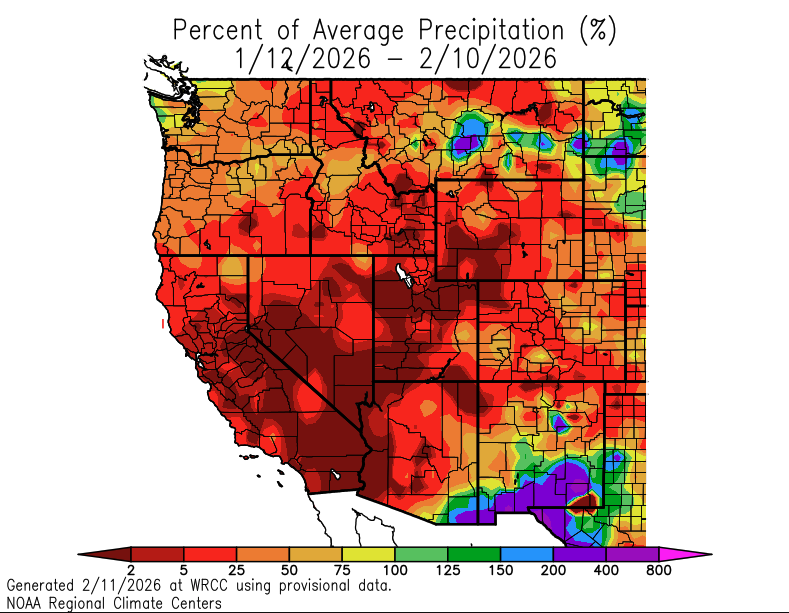

Even with current snowstorms, Colorado’s snowpack this year is, frankly, horrible. The entire state has been in a snow drought with a record-low snowpack. The signs are everywhere: Skiers see it when they hit the slopes. Water providers keep an eye on their reservoir levels and talk about summer watering restrictions. Wildland fire experts gauge fire risk this summer and push people to remove flammable brush from their properties.

Two weeks ago, Inouye skied up to the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory near Gothic, where he and other scientists have been conducting research for over 50 years, and saw exposed dirt patches at 9,500 feet of elevation — areas that would normally be buried by snow. Bees, wildflowers, marmots and more could all be affected by this season’s thin, weak snowpack.

Snow showers in this week’s forecast offer a dose of relief, but they won’t be enough to get the state out of a tough, dry year. The Colorado Sun sought out experts from around the state to see what’s going on — and what we need to watch for looking ahea

What’s happening with the snowpack?

Colorado’s winter has been unseasonably warm with so few snowstorms that the mountain snowpack is the lowest it’s been since 1987.

Climatologists are scouring data from high-elevation federal weather stations, called SNOTEL stations, to gauge what this year’s water supply is going to look like. Stations were built over the years until, by 1987, there were enough to provide a comprehensive look at statewide snowpack.

As a headwaters state, snowmelt from Colorado’s mountains runs in all directions to provide water to communities in 19 downstream states before it reaches the Pacific Ocean and Gulf of Mexico.

This year is not quite as bad as two terrible winters in recent memory: 1976-77 and 1980-81. But some smaller watersheds in the state have been dry enough to break even those records, according to state climatologists at Colorado State University’s Colorado Climate Center who analyzed hand-gathered measurements that date back to 1940.

What has really set this water year apart is how warm it’s been, according to the climate center. Colorado just had the third warmest November and the warmest December in over 130 years of records.

Colorado is over 60% of the way through its snow season, which means there’s still some time to avoid a historically bad, record-breaking year statewide. But the chance of getting a normal snowpack becomes slimmer every day, said Peter Goble, assistant state climatologist at the climate center.

The winter storms this week will help, he said. But even if Colorado had a repeat of 2019 — an above-average snow year — from February through April, its snowpack would still be just below normal.

“We have not yet had a year when we were running really low at this point and then just had a magical second half of the snow season and got all the way back,” Goble said.

Visitation is down at ski resorts

The poor snow year has already taken a toll on ski resorts and local economies.

Vail Resorts last month told investors that visitation to its 37 North American ski areas was down 20% through Jan. 4 compared with the previous season. Company CEO Rob Katz pointed to “one of the worst early-season snowfalls in the Western U.S. in over 30 years” — with snowfall at the company’s Rocky Mountain ski areas in Colorado and Utah down 60% from 30-year averages — as the main reason behind the decline.

The company’s Beaver Creek, Breckenridge, Crested Butte Mountain Resort, Keystone and Vail ski areas account for more than a quarter of resort visitation in Colorado, the most trafficked ski state in the country. Vail Resorts is among several resort operators across the state that are cutting hours for workers as visitation ebbs and the lack of snow limits open terrain.

Colorado Ski Country has indicated its 20 members are seeing visitation declines in the “sizable double digits.”

Sales tax reports and end-of-season visitor counts are not due for a few months but several mountain communities are reporting lodging occupancy declines for the season around 10% as the snow-starved season limps further into February.

Meanwhile, the historic drought across the West has led to resort closures. In Oregon, Hoodoo, Mount Ashland and Mount Hood Skibowl have suspended operations as they wait for snow and Willamette Pass ski area is closed for two days midweek.

The thin snowpack left Colorado’s backcountry slopes with low avalanche danger in the middle of the winter, and that’s unusual, Ethan Greene, director of the Colorado Avalanche Information Center, said.

Since Nov. 1, CAIC has counted 31 people caught in avalanches resulting in three injuries and no fatalities. That compares to 28 people caught in avalanches through mid-February in the 2024-25 season, resulting in three injuries and zero deaths. In the same span of the 2023-24 winter, CAIC tallied 47 people caught in avalanches, with three injuries and two deaths.

For winter sports enthusiasts, more dry days won’t be a great outcome, Greene said. More storms increase avalanche danger, but they also improve riding conditions.

This week’s winter storms bumped the danger level in northern Colorado to moderate and considerable levels Wednesday, up from a low danger rating Tuesday, based on the center’s avalanche danger map.

“We have a very thin and very weak snowpack,” Greene said. “It’s not posing a lot of danger right now, but if we go into a really active weather pattern that could change pretty substantially.”

City water also increasingly in doubt

Near-term droughts are a golden opportunity for Colorado water agencies to tap their long-standing signs declaring the need for more reservoir storage.

Aurora announced the final site choice for the proposed Wild Horse Reservoir in South Park on Tuesday, and pointed straight at the current drought as an urgent reason for building up emergency supplies for the Front Range.

The water provider’s reservoirs are at 60% of capacity, which is lower than the city wants to see for this time of year, particularly with a record-low snowpack, Aurora Water spokesperson Shonnie Cline said. The region would have to get all of its normal snowfall — plus another 50% — over the next two months to get back to average.

The city council will soon decide whether it will declare deeper drought restrictions for this summer, she said. Restrictions aren’t out of the question for another big Front Range water provider, Denver Water, which serves 1.5 million people in Denver and surrounding suburbs.

Denver Water draws 90% of its water supply from the mountain snowpack in the Colorado River and South Platte basins. The snowpack near its water diversion tunnels and pipelines in these basins was 55% and 42% respectively as of Monday.

Northern Water, which serves community water agencies and ditches for 1.1 million people and 615,000 acres, said reservoir storage levels for its Colorado-Big Thompson Project are higher than in previous looming snowpack droughts.

That project “was built for years just like this one — where a low water supply threatened the ability of the farms and cities in our region to produce the economic benefits expected,” Northern Water spokesperson Jeff Stahla said. “What that means is that we have enough water in storage right now to ensure crops get out of the ground and cities can produce the materials needed for this upcoming high-demand season.”

Northern Water has also been in talks for months with members who had bought into a $2.7 billion, two-reservoir and pipeline plan to add storage along the Poudre and South Platte rivers. Some communities have signaled they will drop out because of the massive project’s rising costs, while Northern Water has pointed to communities that stayed in because they need supply for future growth and stability.

The dozen-plus community water agencies receiving Northern Water this year, though, will have to consider drought savings measures.

“We anticipate that communities within our boundaries will likely put in place policies to ensure we don’t waste any water and can ensure that we use the stored water for as long as possible,” Stahla said.

On Thursday, Northern Water’s board will hear a proposal to tap into an additional pool of water, called the administrative pool, that wasn’t used last year. The board will have to consider the possibility that this year’s drought might last longer than one season as it considers how much to draw from reserves, Stahla said.

A deep drought from 2000 to 2002 cut into their reservoir storage and supplies, depleting it so much that it took seven years to recover, he said.

“We recognize that we should be thinking about many variables as we look to release water for 2026,” Stahla said.

It could get too cold for the pikas

The low snowpack could have impacts on critters in the high country.

“Pikas depend on snowpack to insulate them from cold winter temperatures at high elevations, so the low snowpack could potentially make it harder for them to survive the winter,” said Megan Mueller, a conservation biologist with nonprofit Rocky Mountain Wild.

Through the Colorado Pika Project, a partnership between the nonprofit and the Denver Zoo, community scientists collect data in Colorado’s mountains in the summer to help scientists better understand the pika population and how it is being impacted by climate change.

Because the surveys take place in the summer, Mueller said it’s not yet clear what consequences this year’s dry weather will have on pikas. But existing research shows pika populations have gone extinct at sites where winter snowpack was insufficient for insulating them from the extreme cold.

Volunteers seeking to help scientists better understand the impact of this year’s snowpack on Colorado’s pikas can sign up online to join the Pika Patrol.

Ground squirrels, marmots, chipmunks, bears and other mountain mammals might have to use more energy to stay warm in their habitats without that snowy insulation. Burning energy faster could mean some will starve or emerge from hibernation earlier, according to Inouye with the Rocky Mountain Biological Center.

And just like mammals, insects and plants struggle in warm, dry winters.

Colorado has about 1,000 species of native bees, many of which spend winter underground and depend on the snowpack’s insulation.

Inouye has been watching how wildflowers, like aspen sunflowers and larkspurs, bloom in different conditions since 1973. Flowers start to bloom as soon as snow melts. With a thin snowpack, that melt could happen in mid-April, especially on sunnier, south-facing slopes. Wildflowers will start to bloom early and could be stunted by hard freezes that can typically appear through early June.

An early, sparse bloom affects pollen resources, which are key for bumblebees and migrating hummingbirds as they nurture larval bees or lay eggs, Inouye said.

“It’ll certainly be a very early season for the blooming of the wildflowers,” he added. “That’s typically associated with lower numbers of flowers.”

Fire managers fear early start to fire season, severe wildfires

This year’s low snowpack has wildfire managers fearing an early start to fire season and severe fires as the temperatures rise, especially along the Front Range.

“We haven’t seen anything quite like this in 30 years,” the state fire division’s planning section Chief Rocco Snart said.

The lack of snowpack this year reminds Snart of the conditions that led to the “horrific fire seasons” in 2000, 2002 and 2012.

“They were in the same realm as where we’re at today. But now we’re worse than those,” he said.

In those years, more than a dozen notable wildfires ignited amid extremely dry conditions. Hundreds of thousands of acres burned across the state and hundreds of homes were destroyed. In 2000, two human-caused fires destroyed 80 homes on the Front Range, while another fire sparked by lightning scorched 23,607 in Mesa Verde National Park, according to the National Weather Service.

In 2002, six massive fires sparked across the state, including the arson-caused Hayman fire that charred more than 137,000 acres across five Front Range counties and became the largest wildfire in Colorado history at the time. Five firefighters died and more than 600 structures were destroyed.

And in 2012, six massive wildfires rapidly spread amid extreme drought. Among them was the Waldo Canyon fire, which scorched 18,000 acres near Colorado Springs and destroyed 346 structures. Two people died.

If Colorado doesn’t start to see more precipitation soon, Snart said he fears wildfires will begin igniting much earlier than previous years, in March or April, and be fueled by winds. Vegetation will be dry as no new growth will have sprouted by then.

Snart sees wildfire risk along the Front Range as “especially problematic” because it picks up down-sloping winds from the mountains which are a “prime driver” of early season fires.

Fire risk is also very high along parched lower elevations of the Western Slope, he said.

Residents can take advantage of the warmer weather and start mitigating areas around their homes and being cautious of any activity that could cause sparks, especially on windy days, Snart said.

Amid “grim” outlook, farmers eye snowpack, forecasts

Jared Gardner apologizes for the interrupting beeps from his tractor’s GPS system as he makes his way across the family’s 3,500-acre farm near Rocky Ford. But he explains that it’s a different technology — the data on his smartphone — that grabs his attention multiple times each day as he considers the fate of the fields where he cultivates alfalfa, corn, sorghum and a mix of watermelons, cantaloupes and pumpkins.

Snowpack numbers, harvested from SNOTEL sites, influence planting in this agricultural corridor of the Lower Arkansas Valley. Snowpack determines runoff, which determines the flows of the Arkansas River, which determines what to grow and what to avoid.

When Gardner Farms plots out a two-year plan for crop rotation, it begins with a best-case scenario of conditions, untethered to limitations of drought. Closer to planting time, lower water estimates may steer operations to a Plan B, which might mean trimming back acreage for the thirstiest crops.

“My brother and I are probably on Plan C or D already, looking at this snowpack,” Gardner said. “It would take a small miracle to turn this thing around in a fashion that you’d say I have an ample supply of water. So for us, the first thing I do is pull corn back, to grow something with the yields that you need to break even in this marketplace. There’s not a lot of wiggle room for failure.”

A little more than an hour east on U.S. 50 near Lamar, Dale Mauch pays less attention to the snowpack numbers than the long-range weather forecasts, which he checks two or three times a day to gauge the fortunes of his 4,000 acres of hay, corn, wheat, oats and sorghum.

He, too, depends on replenishment of the Arkansas River. He pays special attention to the current windy, drying effects of a La Niña system and the promise of moisture from El Niño.

“The transition is supposed to be coming, but it may not be here till May, which could be too late for this year’s snowpack,” Mauch said, noting that his planting plans remain uncertain amid some forecasts that predict up to four feet of snow over the next few weeks.

“The silver lining for us down here by Lamar is we’ve had some storms with pretty good moisture,” he added. “So as far as being dry, we’re not in that bad of shape. We’re in better shape than the mountains right now.”

Overall, experts say the outlook for farmers — and ranchers, whose livestock rely on the same snowpack — leans away from optimism.

“It’s pretty grim,” said Kristen Boysen, managing director of the state Agriculture Department’s Office of Drought and Climate Resilience. “Producers are definitely bracing for the worst, but I don’t think anyone has changed their plans yet.”

Final decisions on what crops to plant, the size of cattle herds based on available water, and where to find extra grazing pastures or hay supplies all need to be made at most farms and ranches within a month, Boysen said. Even if agriculture sees snow over the mountains in the next few weeks, she added, the growing season may already be compromised.

“Across the state, we’ve seen so little moisture, so the soil is really dry,” Boysen said. “So any runoff we get from the mountains will just get sucked up so fast by the soil. And I think peak runoff will be very early. I think they’re crossing their fingers that it rains on their farm.”

Back in Rocky Ford, Gardner remains hopeful that a cold front forecast for the coming days might generate moisture to fulfill a farmer’s innate optimism. But even a foot or so of snow in the mountains probably won’t translate, in the long run, to much relief.

“Unless we just get an epic blizzard in the mountains, that sort of snow is kind of a Band-Aid for a bullet hole right now,” Gardner said. “And Colorado knows that. I think everyone in Colorado understands what a lack of snowpack means to the state, whether you ski on it, or irrigate with it, or just want to drink it.”

Colorado Sun reporters Olivia Prentzel, Michael Booth, Kevin Simpson and Jason Blevins also contributed to this report.

Print

Print