The summer days of 2019 in Castle Rock were hot and endless. School teacher Kirsten Schuman, pregnant with her second child, wearily watered her suburban yard only to see it go brown almost immediately, week after week.

But then a friend told her about a new city contest to win an $11,000 yard makeover, one that would remove the beleaguered bluegrass and install an array of low-water use plants, trees and grasses.

Prospects for her lawn suddenly took an exciting turn. In a matter of minutes, the Schuman family mobilized.

She and her husband, a high school football coach, painted slogans on their cars. They posted on neighborhood message boards, and on Facebook and Twitter. They made a video of their oldest child in an empty plastic pool.

“It was intense,” she said. “My husband and I are both very competitive.”

That fighting spirit paid off. They won and now have a low-water use landscape that blooms freely and costs less.

Kirsten Schuman, her husband, Max Schuman, and daughters Mayla, 11, and Eleanor, 1, stand in their newly installed landscape in the front yard of their home on July 30, 2020 in Castle Rock. The family won the ColoradoScape Makeover contest, which resulted in the new water-conscious landscape. Credit: Jeremy Papasso, special to Fresh Water News

And that’s what it’s like to live in Castle Rock, a fast-growing community where water is scarce and the pressure to conserve runs high.

Conservation as buffer

Colorado water officials hope more communities follow in Castle Rock’s footsteps. The state wants to dramatically reduce water use in the next 30 years as a buffer against intense drought and looming water shortages caused by population growth.

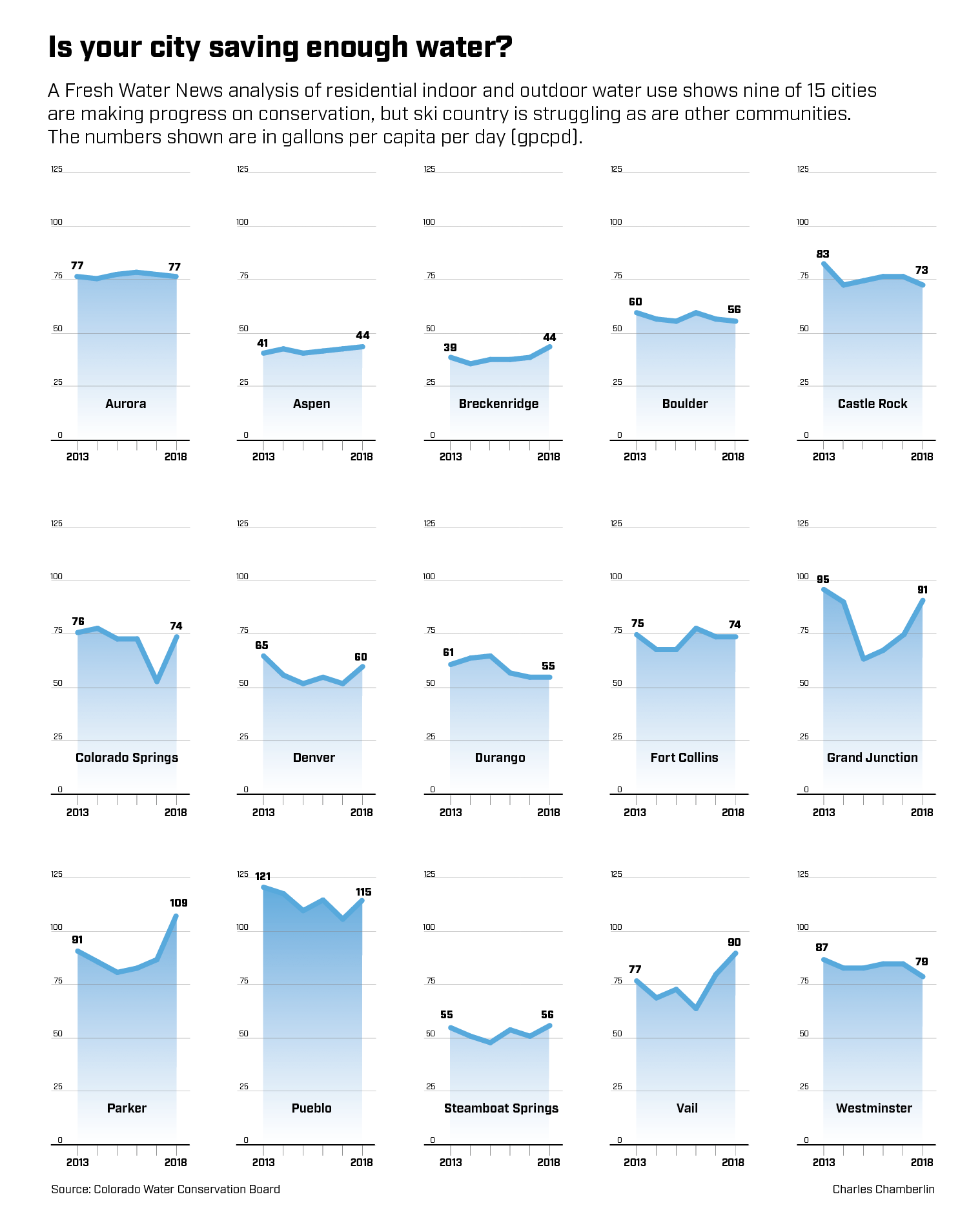

But a new analysis of residential water use by Fresh Water News shows statewide savings in recent years may have stalled out, with some cities seeing conservation efforts pay off big, while for others use remains flat or is rising.

The analysis used data collected by the state from 2013 through 2018, the latest year for which complete data sets were available, and examined only metered, residential indoor and outdoor use. Under state law, data must be reported by water utilities and districts delivering more than 2,000 acre-feet of water annually, and who wish to borrow money from the state. Depending on the year, 40 to 45 communities report data. To see how much water your home town uses, click here.

The Fresh Water News analysis looked at data for 15 cities representing the state’s different geographies and major population centers.

Nine of those, including Denver, Castle Rock, Colorado Springs, Durango, and Grand Junction, among others, have succeeded in cutting residential water use since 2013. Castle Rock leads the state with a 12 percent reduction over the six-year period, while Denver saw its water use drop 8 percent. Grand Junction reduced its use 4 percent and Colorado Springs has ratcheted its use down 3 percent.

The struggle to conserve

At the same time, however, several communities, including ski towns and the fast-growing south Denver metro community of Parker, continue to struggle. Vail, for instance, saw its water use rise 17 percent between 2013 and 2018, while use at the Parker Water and Sanitation District rose 20 percent.

Statewide, when combining results for all 15 cities examined, per capita water use during that period showed virtually no reduction. Daily per capita use in 2013 registered at 73.66 gallons per person per day. By 2018 it was down to 73.13, a reduction of less than 1 percent.

At 73 gallons per capita per day (gpcpd), Colorado is likely the envy of other states, where that metric is often well over 100 gallons per day, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, which has tracked national water use data and reported on trends since 1950.

Tamara Ivahnenko, a water conservation researcher with the USGS in Pueblo, said Colorado has historically been a leader in reducing water use.

And she gives the state high marks for establishing the conservation database, something only a handful of states, such as Texas and California, have done.

“Especially in the West there are water-stressed cities. We really have to be careful,” she said.

Colorado’s data collection effort comes under a major conservation bill approved by state lawmakers in 2010. They sought to shed more light on water conservation practices and to encourage communities to reduce water as one tool in staving off shortages.

Bruce Whitehead, a former state senator from Durango, was a sponsor of that legislation. He said getting down to real numbers was and remains critical to successful conservation.

“Without having the law in place, the way things were being reported prior to that was inconsistent,” he said. “If you can start zeroing in on what these numbers are, it gives you a starting point.”

Xeriscaped gardens are a conspicuous feature throughout Las Colonias Park in Grand Junction, Colo., Monday, Oct. 26, 2020. According to state data, residential water usage in Grand Junction declined 4 percent between 2103 and 2018. Credit: Barton Glasser, special to Fresh Water News

Kevin Reidy, water conservation specialist for the Colorado Water Conservation Board, oversees the state’s conservation programs and the database.

The more recent data could indicate that things have stalled, he said. But he said it’s also difficult to gauge how much conservation is occurring in such a short period of time because of the high variability caused by wet and dry years. The state started collecting the data in 2013.

A technical update to the Colorado Water Plan released last year examined an earlier time period, from 2008 to 2015, and used data based on river basin geography rather than town-by-town. That analysis showed statewide water use had dropped roughly 5 percent, Reidy said.

Uphill battles

Communities in Douglas County and other fast-growing areas are often served by water districts that have little if any control over how cities regulate development. That means that things such as lawn size and requirements for water-saving appliances are typically out of the water district’s control. Such is the case at the Parker Water and Sanitation District.

Billy Owens, who tracks the data for the district, said her district has worked hard to bring down water use, in part because it is fast-growing and it relies heavily on non-renewable groundwater. In addition to the town of Parker, the district serves parts of Lone Tree, Castle Pines and unincorporated Douglas County.

That 2018 was a hard-hitting drought year likely bumped up their use numbers, Owens said, as residents used more water on lawns and gardens. That same year the district also began serving several large new developments, where initial watering needs were high.

Reducing water use has also been a challenge for ski towns. Many have introduced elaborate conservation strategies, but the influx of visitors every winter and summer, and the prevalence of second homeowners who have lush landscapes to water and who may be less sensitive to high-priced water bills make it difficult to achieve savings, ski town officials said

All four ski towns in the analysis, Aspen, Vail, Breckenridge and Steamboat, have relative low per capita daily use, in part because their transient tourist populations are included in the equation even though tourists aren’t contributing year-round to those communities’ water use statistic.

But even at the lower per capita numbers, the analysis shows their water use has increased at varying levels since 2013.

For example, in 2013, the Vail region was using 77 gallons per person per day, according to the Fresh Water News analysis, a number that rose to 90 by 2018.

Jason Cowles, manager of engineering for the Eagle River Water and Sanitation District, which serves the region, said the rise likely reflects the area’s ongoing struggle to manage second-home water use, climate change, and the dramatic influx in visitors every year.

In the region, more than 50 percent of homes are occupied by part-time residents, whose landscapes are watered even when owners aren’t in residence.

Because hot weather is arriving earlier and staying longer due to climate change, residents are turning on sprinkler systems in May and leaving them on into the fall, Cowles said.

The winning formula

Castle Rock has achieved significant savings with an innovative collection of initiatives, including aggressive water pricing, leading-edge construction technologies, and popular community outreach programs. The ColoradoScape Makeover, introduced in 2019, has helped lure hundreds of homeowners like the Schumans into the water-saving fold.

“When we bought our house, we realized we were dumping a lot of water into the front and back yards. But it didn’t look like we were doing anything and it was expensive,” Schuman said. “So the contest and makeover were amazing.”

Even more effective, according to Mark Marlowe, Castle Rock’s director of water, are the strict guidelines developers must follow if they want to build new homes. Lot sizes are sharply limited; bluegrass is no longer allowed; homeowners have custom water budgets; and development parcels that haven’t been grandfathered in must show how new technologies will reduce water use beyond existing baselines.

“We let developers tell us how they’re going to do better. We want them to be a little creative,” Marlowe said.

Castle Rock also offers generous rebates to homeowners who buy water-saving toilets and other appliances. But if they want a rebate, they have to go to special water conservation classes. And those routinely sell out, according to water conservation specialist Linda Gould. In recent years more than 3,300 people have gone through the city’s classes.

The city also takes a dim view of landscapes that don’t perform as promised. If a developer or homeowners’ association uses a registered landscaper and the system doesn’t perform properly, the landscaper can lose their license to work in the city.

Marlowe says the tight coordination between the planning department, the water resources division, and the city council are paying off.

“The council has been very supportive of everything we’ve been trying to accomplish, and our ratepayers are motivated,” he said.

Lawn sizes in Castle Rock are sharply limited to save water, with some homeowners opting to use artificial turf for convenience and to help keep water bills low. Oct. 21, 2020. Credit: Jerd Smith, Fresh Water News

Will Colorado reach its goal?

The Colorado Water Plan, an initiative coordinated by the Colorado Water Conservation Board (CWCB) aimed at making sure Colorado has enough water for its cities, farms and environmental needs, has set a goal of conserving 400,000 acre-feet of water by 2050.

That’s part of a wider plan that also envisions developing new water supplies, as well as reusing and recycling more water to make supplies last longer.

Heather Cooley is director of research at the San Francisco-based Pacific Institute. She said communities across the West are making healthy strides in conserving water, and new technologies, as well as leak detection initiatives, should allow states such as Colorado to do much more.

“We think there is still significant opportunity to reduce use even further,” Cooley said.

Castle Rock hopes to cut its overall water use number to 100 gallons per capita per day by 2050, down from its current level of 115 gpcpd. This number includes commercial and industrial uses, not just residential uses, which Fresh Water News examined.

To help cities hit their goals, the CWCB has also launched an ambitious program to help utilities plug leaks in their systems, a problem that is common and wastes millions of gallons of water a year. At some utilities, that loss can be as high as 10 percent of delivered water.

Jeff Tejral, manager of water efficiency at Denver Water, said the state as a whole is making good progress on the water conservation front.

“I think that there are things to be done that we haven’t actually worked on yet, like how to engage fully with our customers. But some things are working. I take these numbers as a win,” Tejral said.

Technical finesse

Cooley said technology is advancing rapidly as well, offering hope for even more savings. New devices continue to set low-use records. Clothes washers coming out this year are using even less water than those sold just five years ago. Homeowners can attach rain monitors to their houses that automatically shut down sprinklers when it rains. Almost anyone can now install an app on a cell phone that alerts them when their water use rises beyond a set level.

The CWCB’s Reidy said Coloradans are becoming more water savvy all the time.

“We’re definitely more engaged than we were a decade ago and way more engaged than we were 20 years ago,” Reidy said. “And we have 30 years to hit the goal. I think we’re on a good path.”

Former lawmaker Bruce Whitehead said he remains concerned, particularly about the ongoing disconnect between land used for new growth and water conservation plans.

He also thinks the pressure to conserve will continue to rise. And because Colorado sits at the top of the drought-stressed Colorado River system, the state needs to be able to demonstrate to its neighbors to the south that it can use each drop well.

“We need to know what’s actually taking place,” Whitehead said. “If we’re looking at taking additional water from the Colorado River [as some Colorado cities are], we should be doing everything we can statewide to put conservation practices in place.”

Data journalist Burt Hubbard contributed to this report.

Jerd Smith is editor of Fresh Water News. She can be reached at 720-398-6474, via email at jerd@wateredco.org or @jerd_smith.

Fresh Water News is an independent, nonpartisan news initiative of Water Education Colorado. WEco is funded by multiple donors. Our editorial policy and donor list can be viewed at wateredco.org

Print

Print