What climate change means for Colorado’s water supply

Bill Waschke, a farmer in the small southwestern Colorado town of Dove Creek, watched last summer as more than 80 percent of his crops withered in the field, too dry and malnourished to harvest.

At the same time, David Costlow, a former rafting guide and the head of the Colorado River Outfitters Association, watched as rivers like the Animas near Durango and Clear Creek outside of Golden trickled in midsummer at a fraction of their historic flows.

And Gary Kyte, chair of Pine Drive Water District southwest of Pueblo, watched as ash from an old forest fire burn scar washed into North Creek and incapacitated his water treatment plant.

For Coloradans of all stripes, the summer of 2018 was a stark indication that climate change is already affecting the state. When it comes to precipitation, natural variability is so extreme in Colorado that it can be difficult to pick out the signal of climate change. One hot, dry year isn’t necessarily climate change. Yet the 2018 water year (October 2017 through September 2018) showcased many of the symptoms that scientists associate with a warming West. It was Colorado’s hottest and second driest year in recorded history—and likely a preview of the state’s future.

There is widespread consensus among climate scientists that the warming now taking place is primarily due to human-caused emissions of heat-trapping greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide and methane. Some level of warming is “baked in” to the climate system by the greenhouse gases we’ve already emitted: A 2017 study published in the journal Nature Climate Change found that even if greenhouse gas emissions had stopped in 2017, the globe would still warm an additional 2 degrees Fahrenheit by 2100. That means that Coloradans should expect a future with earlier runoff, less spring snowpack and more intense fires, droughts and floods. Myriad state planning efforts are underway to address these impacts and mitigate Colorado’s contribution to the problem. The Climate Change in Colorado Report, the Colorado Climate Change Vulnerability Study and the state’s Drought Mitigation and Response Plan detail current and anticipated impacts from climate change along with adaptation strategies, while the Colorado Climate Plan establishes clear statewide emissions reduction goals. These efforts make clear that those Coloradans who recognize climate’s connection to our water future are implementing measures—from building redundant water systems to planting new crops—to increase their resilience, while also reducing their climate impact.

The Forecast

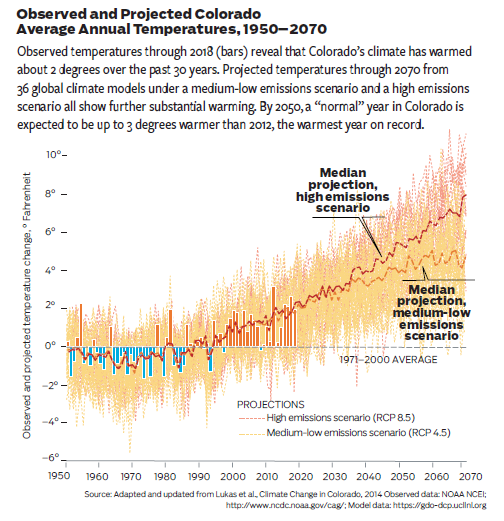

The myriad effects of climate change on Colorado’s environment and economy begin with a basic fact: It’s getting hotter. As of 2012, Colorado’s annual average temperature had increased by about 2 degrees Fahrenheit over the previous 30 years, and 2.5 degrees over the previous 50 years, according to the 2014 report Climate Change in Colorado by the Western Water Assessment at the University of Colorado-Boulder in partnership with the Colorado Water Conservation Board. Since then, the warming has continued unabated, with 2015, 2016, 2017 and 2018 coming in among the eight warmest years since 1900. Future levels of warming, most agree, will depend in large part on future greenhouse gas emissions: Under a “medium-low” emissions scenario, Colorado’s average temperature could be between 2.5 degrees and 5 degrees Fahrenheit hotter by 2050 than the 1971-2000 baseline. A “high emissions” scenario could push that warming to 6.5 degrees Fahrenheit by mid-century. Two degrees of warming would make Denver feel like Pueblo, says Jeff Lukas, the report’s lead author, and with 6 degrees of warming, Denver would feel like Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Projected effects of climate change on Colorado’s precipitation are less clear. Even without climate change, Colorado is no stranger to extremes. There is huge natural variability in rain and snow across the state, with parts of the San Luis Valley in southern Colorado seeing just 7.5 inches of precipitation per year while parts of the central mountains near the Continental Divide get 60 inches. That’s in addition to tremendous year-to-year variability. Global climate models diverge as to whether climate change will drive more or less future precipitation across the state. There is broader consensus among models that summer precipitation will decrease more than winter precipitation, and that rain and snow is more likely to decrease in the southern part of Colorado than in the north. Due to warming, Colorado’s snow-line is expected to move to higher elevations, bringing rain rather than snow to parts of the high country and increasing the risk of winter floods from rain-on-snow events. Precipitation is also expected to concentrate in fewer, heavier storms, says Lukas, which could increase the risk of flooding.

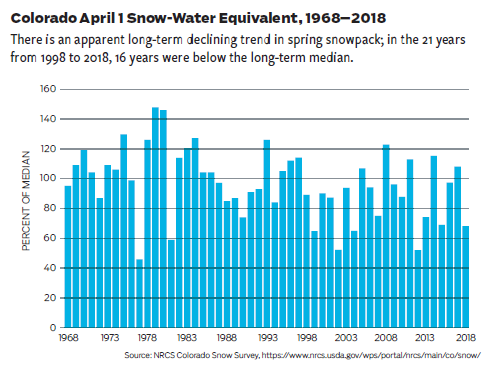

Regardless of future precipitation, Colorado’s spring snowpack and runoff have likely already declined due to climate change. Those trends are projected to continue. A 2018 study published in the journal Climate and Atmospheric Science analyzed 699 snow monitoring sites across the West and found that since 1915 the “snow-water equivalent,” or the amount of water contained in snowpack on April 1, has declined by 21 percent. Because more precipitation is falling as rain, compounded by increases in sublimation—where snow exposed to sunlight transforms directly from a solid to a vapor— “we’re getting less snowpack out of our precipitation,” Lukas says. Less snowpack equates to less water that melts off and can be diverted for use in the spring and summer. The other challenge: Runoff is peaking one to four weeks earlier than it did 30 years ago. By 2050, peak runoff is projected to shift another one to three weeks earlier. That has major implications for water providers, farmers, rafters, wildlife, the environment, and virtually everyone else in Colorado, since earlier peak runoff will be increasingly out of sync with the traditional agricultural and municipal irrigation seasons and the summer rafting and fishing seasons, not to mention peak blooming and wildlife migration seasons.

Native flows in the Colorado River Basin have fallen by about 18 percent since the current drought began in 2000, according to Brad Udall, a senior water and climate research scientist at Colorado State University’s Colorado Water Institute. In a February 2017 paper in the journal Water Resources Research, Udall and his co-author Jonathan Overpeck found that about one-third of that reduction is due to the higher temperatures brought on by climate change. Thanks to factors like increased sublimation, more water absorbed by plants, and longer growing seasons, Colorado River runoff has declined by about 4 percent for every degree Fahrenheit of warming in the basin, Udall says. Five degrees of warming by mid-century, then, could reduce Colorado River flows by 20 percent below the 20th century average, and flows could be 35 percent lower by later in the century if warming continues and precipitation stays the same. For a river that supplies water to 40 million people across the West, this is a dire forecast.

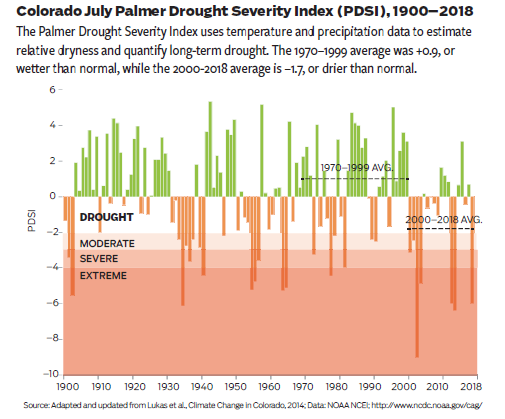

Compounding that projection is a likely increase in the frequency and severity of droughts under climate change, according to the 2015 Colorado Climate Change Vulnerability Study by the Western Water Assessment and Colorado State University. Droughts are typically characterized by a lack of precipitation and unusually hot temperatures.

Rising temperatures will mean that average years are more like drought years and that any given drought evaporates more precipitation and dries out the land more than it would have in the absence of climate change, making droughts more severe and leading to devastating impacts on crops, livestock, river flows, and municipal water supplies. Paleo-drought records gleaned from analyzing tree rings show that droughts longer than the ongoing 18-year event have occurred in the Colorado River Basin in the past, before the dawn of greenhouse gas emissions. That raises the prospect of multi-decadal droughts, sometimes called megadroughts, in the coming century, exacerbated by climate change.

Wildfires, too, have become both more frequent and more severe in the West since the mid-1980s. That’s due to several climate change-related factors, including droughts and outbreaks of tree-killing pests like the mountain pine beetle. According to the Fourth National Climate Assessment, published in 2018, half of the acreage that burned in the southwest between 1984 and 2015 was the result of climate change.

Impacts and Adaptation: Water Utilities

Perhaps no Colorado industry feels the urgency of preparing for the future toll of climate change as keenly as the state’s water providers. Already, due to warming, utilities like Denver Water are seeing impacts to snowpack and runoff.

In the spring of 2018, snowpack in Denver Water’s collection system above Dillon Reservoir peaked at 113 percent of normal, but—thanks to a warm, dry spring and the possible effects of low soil moisture and more water absorbed by plants—the inflow to Dillon Reservoir from April through July was just 71 percent of normal. “If we don’t get moisture in the spring, or it gets hot, spring runoff might not look very good,” says Laurna Kaatz, Denver Water’s climate program manager. And with less runoff flowing into Denver Water’s reservoirs, less water is available for its 1.4 million people. “A handful of storms will make or break our year,” Kaatz says.

To cope with earlier runoff and unpredictable yields from snowpack, and to provide insurance against interruptions in its collection system caused by disasters like wildfires and more intense droughts, Denver Water is seeking to diversify its portfolio of water investments. An example includes enlarging Gross Reservoir southwest of Boulder, which will allow the utility to store more water in wet years. Expanding reservoir storage allows utilities to deal with changes in runoff by capturing and storing water until it is needed. Water stored in wet years can be critical for weathering future droughts. Planning, permitting and expanding or building new reservoirs can take decades, and changes to the timing and amount of runoff are happening now, so utilities need to consider an “all of the above” approach to prepare for climate change, says Kaatz. This includes efficiency, reuse, new supply investments, and exploring less traditional options. For example, there are ways to increase storage besides surface reservoirs. Denver Water is piloting aquifer storage and recovery, where surface water is injected into groundwater formations for storage and later use.

Towns of all sizes can boost their climate resiliency without tackling expensive capital projects. Municipalities can encourage water conservation and maximize their existing supplies by enacting water-smart zoning regulations or building codes, or can factor water into their land use plans. Water providers can also modify the structure of their tap fees, tweak their water pricing tiers or even bill customers more frequently to encourage conservation and efficient development.

Regardless of their efficiency, small communities reliant on just one water source run the risk of having their entire water supply curtailed by the wildfires that are becoming more frequent and intense under climate change. Gary Kyte, chair of the Pine Drive Water District, which serves 166 households in the Beulah Valley roughly 30 miles southwest of Pueblo, experienced this last July when a rainstorm soaked a 4,000-acre wildfire burn scar in the community’s watershed, sending ash into North Creek and forcing Kyte to shut down his water treatment plant. By the fall of 2018, the plant remained closed as Pine Drive piped about 9,000 gallons of water a day from the neighboring community of Beulah. (Fortunately, Pine Drive and Beulah had linked their water systems following the devastating drought of 2002, when both communities were forced to truck water from Pueblo). The increased cost of buying water from Beulah is forcing Kyte to raise water rates to keep the utility afloat. “All these impacts from wildfire just pile on,” he says. To adapt, Pine Drive and Beulah are exploring the prospect of merging their water systems, potentially saving money by sharing a water treatment plant. And Pine Drive has contracted engineers to hunt for a deep-well groundwater source that could reduce the community’s reliance on surface water. Maintaining a diversity of water sources in a range of locations allows water utilities to remain resilient as the climate changes.

Wheat stubble dries as a cover crop sprouts beneath in a no-till field facing the La Plata Mountains at the Southwestern Colorado Research Center in Yellow Jacket, Colorado. Here, researchers are using a cover crop/wheat rotation with a cover crop seed mix of winter pea, hairy vetch, triticale, oats, forage radish, and rapeseed. Courtesy Colorado State University’s Southwestern Colorado Research Station

Impacts and Adaptation: Agriculture

Bill Waschke could only harvest about a fifth of his crops in the summer of 2018. He left the rest desiccated and useless in the field, as the southwestern Colorado town of Dove Creek where Waschke grows 100 acres of sunflower, safflower and wheat suffered through its third consecutive year of serious drought.

Dove Creek sits 35 miles northwest of Cortez near the Utah border, and Waschke, who serves as board president of the Dove Creek Conservation District, has been farming there since 1984. Over the summer, drought forced Dove Creek ranchers to sell off about 75 percent of their cattle herds—Waschke’s sister sold off half of hers—and Waschke watched neighbors struggling over whether to spend their last few dollars on crop insurance or tractor fuel. The town that usually receives 12 inches of rain per year only saw four inches in 2018.

While projections of future precipitation remain uncertain, Colorado’s Water Plan projects that warming in southern Colorado will drive a longer irrigation season and a decrease in annual streamflow in the years to come, and that, “even moderate increases in precipitation will not be sufficient to overcome the drying signal.” If drought continues much longer, says Waschke, “it could turn Dove Creek into a ghost town.” The community has struggled for decades to convince its young people to take over their parents’ farms and ranches, and the ongoing drought makes that proposition much less attractive. When Waschke was growing up in Dove Creek in the 1970s, there were 40 students in his high school class; the current class has just 10. “Agriculture is a big part of the community here, but these days our largest export is our children,” he says.

Agriculture is a vital part of Colorado’s identity and economy, but climate change threatens food production and the livelihoods of producers in the state, most obviously for its potential to worsen and prolong droughts, change the timing and amount of runoff, and increase summer temperatures. The more frequent and severe droughts projected under climate change will have serious economic consequences. A 2013 study from Colorado State University found that the 2012 drought caused an estimated agricultural loss in the state, as declining crop revenues translated into reduced spending in agricultural communities. Dryland crops like wheat show declining yields in many climate model simulations due to heat stress and lack of water. Cindy Lair, conservation program manager at the Colorado Department of Agriculture, believes dryland farming in parts of eastern Colorado will likely become untenable in the future, as the temperature rises, yields fall, and crop insurance rates increase. One option for these growers, she says, would be to re-seed their lands with native grasses and move into grazing livestock, a transition that will take significant time and money and comes with its own climate challenges.

Irrigators, too, will be impacted as runoff patterns change, growing increasingly out of sync with the traditional growing season. A decrease in the availability of water in late summer squeezes junior water-right holders and those without access to storage. Some farmers who find their water rights increasingly less useful for agriculture may choose to pad their incomes by leasing water to cities. The water demand of those urban water providers could rise by up to one million acre-feet by 2050, according to Colorado’s Water Plan.

“Farmers can adapt to climate change by treating some portion of their water rights as a crop and using that to their advantage by entering into dry year options or some other arrangement with municipalities,”- Anne Castle, a senior fellow at the University of Colorado’s Getches-Wilkinson Center for Natural Resources, Energy and the Environment.

Other “alternative transfer methods” include deficit irrigation and rotational fallowing. “That could allow them to supplement, or maybe even improve, their income stream and hedge against commodity price volatility, while adapting to having less water,” Castle says.

Yet farmers are notoriously hardy, and some are making on-farm adaptations to cope with the changing climate. Waschke is a pioneering grower who has adopted “mulch till” practices where he plants directly into the residue of his previous crop. He is also testing a cover crop rotation of dry beans and corn followed by winter wheat. Cover cropping, where nitrogen-fixing species are planted during fallow periods to improve soil health and water retention and to prevent erosion, is increasingly popular in areas with sufficient water to support a cover crop.

Impacts and Adaptation: Tourism and Recreation

In June of 2018, southwestern Colorado was a case study in the vulnerability of Colorado’s tourism economy to extreme weather. The 416 Fire prompted the Forest Service to close the San Juan National Forest for 10 days, and the Durango and Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad—which ferries tourists between Durango and Silverton in the summer—was shut down for nearly six weeks. These closures at the height of the tourist season wreaked havoc on Silverton’s economy: Scott Fetchenhier, who owns Fetch’s Mining and Mercantile in Silverton and serves as a San Juan County Commissioner, says his business was down 30 percent in June and 7 percent in July compared to the previous year. Town-wide sales tax figures mirrored those trends.

The water level in Ridgway Reservoir, pictured here in August 2018, steadily declined last summer. Photo by William Woody

“There were people canceling their August trips to Silverton even though the fire was in June,” Fetchenhier says. “After a dry winter, businesses in town needed a good summer, but the county wound up declaring Silverton an economic disaster zone for the summer.” As an elected official, Fetchenhier advocates for economic diversification as a way to blunt the impact of any particular disaster on Silverton’s economy, promoting everything from jeep tours and all-terrain vehicle rentals to mountain biking and hiking. Yet as forest fires become more common and intense, they have the potential to hamper these activities, he says. When Colorado’s U.S. senators Michael Bennet and Cory Gardner and Rep. Scott Tipton visited Durango in June to see the impact of the 416 Fire, Fetchenhier testified before them. “I said, ‘We are dealing with fire because of drought, and drought because of climate change. You guys need to deal with climate change,’” he recalls.

From smoky air to public land closures, and from lack of snow to low stream runoff, climate change directly threatens Colorado’s tourism and recreation industries. “This changing climate is going to affect the number of days you can ski, the number of days you can fish, and how often there are high flows for rafting and kayaking,” says Brad Udall.

In Durango last summer, rafting outfitters were also feeling the pinch of low snowpack and early runoff. Flows in the Animas were below 25 percent of average for most of the year. Many other Colorado rivers saw similarly dismal flows. David Costlow of the Colorado River Outfitters Association (CROA), which represents Colorado’s more than 175 rafting companies, said some outfitters bussed their guests from low-flow areas to rivers like the mainstem of the Colorado, which has more reliable flows due to upstream reservoir releases. At press time, it was too early to know the economic impact of 2018’s low flows. But in 2012, another drought year, Colorado rafting companies saw a 17 percent decline in visitation and a 15 percent decline in revenue compared to the year before. “If average streamflow decreases in the future—a likely outcome across the climate projections—resulting competition for diminishing resources could impact rafting, fishing, and other recreation activities along with aquatic habitats,” reads the 2015 Colorado Climate Change Vulnerability Study.

After experiencing major droughts for three of the past 18 years (in 2002, 2012 and 2018), Costlow says Colorado’s rafting guides have adapted by using smaller boats, lightening their loads to avoid running aground on exposed rocks, and tailoring the message of “low water, but not no water,” to attract tourists during dry times. Yet the rafting industry is highly tied to the school calendar and the timing of summer vacations. If peak runoff continues to decline and shift earlier—as reports like the Colorado Climate Change Vulnerability Study project—it could significantly shorten the rafting season, Costlow says.

Perhaps Colorado’s most iconic business to face a direct threat from climate change is the ski industry. Many projections, including those contained in the 2014 report Climate Change in Colorado, indicate that global warming will shorten the ski season by boosting winter temperatures, increasing the number of frost-free days, bringing rain to high elevations at times when it previously snowed, and shrinking the window where conditions are cold enough for man-made snowmaking. A 2014 report from the Aspen Global Change Institute, a climate science nonprofit, projected that Aspen will see all of these changes in the coming decades, and found that the city’s frost-free period has already lengthened by over one month since 1940.

Officials at the Aspen Skiing Company confirm they’ve seen evidence of warming. “We are noticing that both seasonally and in any given opportunity, the window for snowmaking is getting smaller,” says Auden Schendler, vice president of sustainability for the Aspen Skiing Company (SkiCo). That snowmaking window is based on cold temperatures, but snowmaking also depends on water availability. The company obtains much of its water for snowmaking from high alpine streams including Maroon Creek and Castle Creek, leaving SkiCo vulnerable in dry years when there is little water in these streams by late fall. Yet starting in 2004, SkiCo began decoupling its water supply from streamflow at its Snowmass ski area by constructing a network of tanks and ponds across the mountain where up to 5 million gallons of runoff can be stored over the summer and used for snowmaking in the fall, regardless of creek water levels.

Climate modeling commissioned by SkiCo from scientist Cameron Wobus of Lynker Technologies shows that if greenhouse gas emissions continue at their current rates, Aspen’s ski season could be up to 30 days shorter by 2050 and up to 50 days shorter by 2090. Previous research by Wobus published in the journal Global Environmental Change in 2017 projected that virtually all U.S. ski areas would see reductions in their season lengths by 2050 under current emissions trends, with reductions in some areas exceeding 50 percent by 2050 and 90 percent by 2090.

“If emissions continue at current rates, I would expect skiing to be gone except for abbreviated seasons at high-elevation resorts—probably by mid-century, but definitely by later century,”-Auden Schendler, Aspen Skiing Company

Economically, SkiCo and other ski area operators are adapting by expanding their summer recreation offerings, Schendler says, from mountain biking to hiking to frisbee golf. SkiCo is also investing in hotels to diversify its income stream, and purchasing resorts across the country to hedge its bets. “You might have a bad snow year in Colorado, but a good snow year in California,” Schendler says. “So we’re diversifying our business nationally.”

Getting to Zero: Mitigation

As Coloradans adapt to keep life and water running amidst the signals of climate change, they’re also exploring ways to cut greenhouse gas emissions to mitigate its impact.

“In Colorado, water issues and potential shortages are one of the primary reasons that we have to deal with climate change,” says Stacy Tellinghuisen, senior climate policy analyst at Western Resource Advocates and co-author of the 2017 report Colorado’s Climate Blueprint. “And if we want to avoid the worst impacts, we don’t have time to wait for technology to continue developing and getting cheaper before we act.”

Cars on I-70 across the state but not without impact. Transportation is Colorado’s second-largest source of greenhouse gas emissions, behind emissions from electricity generation. Adobe Stock photo

A U.N. report released in October 2018 found that many of the worst global impacts of climate change—from sea level rise to devastating heat waves to food shortages that spur refugee crises—will occur with an increase in global average temperature of just 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial levels. (“Pre-industrial” is broadly defined as the period before humans began burning fossil fuels in the late 1700s.) The same report says, “Global warming is likely to reach 1.5 degrees Celsius between 2030 and 2052 if it continues to increase at the current rate.” And the fourth edition of the U.S. National Climate Assessment, a report authored by over 300 scientists from 13 federal agencies and released in November of 2018, found that the fires, droughts, crop losses and other damage brought on by climate change could reduce the size of the U.S. economy by about 10 percent by the end of the century if nothing is done to reduce emissions.

So what’s Colorado’s role? In July 2017, Colorado joined the U.S. Climate Alliance, a coalition of governors committed to meeting the goal that the U.S. government set as part of the 2016 Paris Climate Agreement: to cut U.S. emissions between 26 and 28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025. Upon joining the alliance in July of 2017, then-Governor John Hickenlooper announced that Colorado would reduce statewide greenhouse gas emissions by 26 percent from 2005 levels by 2025, cutting emissions from electricity by 25 percent by 2025 and reducing up to 2 percent of annual electricity sales by 2020 through efficiency improvements. Colorado emits most of its greenhouse gases through electricity generation, transportation and industry.

Both before and following Colorado’s climate commitment, the state unveiled large-scale initiatives to cut emissions. In 2014, Colorado became the first state in the country to regulate methane emissions, a greenhouse gas about four times more potent than carbon dioxide. Between 2015 and 2017, the number of methane leaks found on oil and gas drilling sites fell by 52 percent, according to an August 2018 report from the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment.

At the utility level, Colorado’s Renewable Energy Standard (RES) was established in 2004, making it the first voter-led RES in the nation, according to the Colorado Energy Office. Since 2004, the legislature has strengthened the RES three times. It now requires that investor-owned utilities generate 30 percent of their electricity from renewable sources by 2020, and cooperative utilities generate 20 percent of their electricity from renewables by that year. It has the added benefit of minimizing water use in electricity generation, since producing renewable energy requires substantially less water than traditional coal- and natural gas-fired power plants. Xcel Energy’s Colorado Energy Plan, approved by the state’s Public Utilities Commission in August 2018, will cut carbon dioxide emissions from electricity by 60 percent by 2026 and boost renewables like solar and wind energy to 55 percent of the utility’s energy mix, exceeding the goal of the RES. In November, Xcel announced plans to cut carbon emissions across the eight states where it operates by 80 percent by 2030 and 100 percent by 2050. And Colorado Governor Jared Polis has advocated transitioning Colorado to 100 percent renewable energy by 2040.

Transportation is Colorado’s second-largest source of greenhouse gas emissions, but will likely become the largest source as the electrical grid grows cleaner through the replacement of coal with renewable energy. “Transportation is the area that is going to be really challenging over the next 10 years,” says Tellinghuisen.

“Change happens slowly when you are relying on people to buy a new vehicle and they only do that every 10 or 15 years.”-Stacy Tellinghuisen, Western Resource Advocates

Colorado’s government is working from several angles to reduce transportation emissions, including helping local governments encourage compact, dense and transit-oriented new developments designed to reduce residents’ vehicle miles traveled. In November 2018, the state’s Air Quality Control Commission voted to join 12 other states and the District of Columbia in adopting California’s strict fuel efficiency standards for passenger vehicles . In January 2018, Colorado also adopted a plan laying the groundwork for the construction of electric vehicle (EV) charging stations around the state to encourage Colorado drivers to use electric vehicles. ( In May of 2019, the Colorado Air Quality Control Commission will weigh whether to adopt a zero-emissions vehicle program, wh would mandate that a certain percentage of all cars sold in Colorado be emissions-free. Such mandates have helped induce carmakers to invest heavily in electric vehicles: General Motors announced in 2017 that it would have 20 models of electric vehicles on the market within six years, with the ultimate goal of transitioning to an all-electric fleet.

Thanks to these initiatives, Colorado is roughly on track to meet its emissions reduction goals. Yet global and state commitments are not yet strong enough to limit warming to 1.5 or even 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial levels. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the scientific body that produces U.N. climate change reports, says limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) will require reducing emissions by 45 percent below 2010 levels by 2030, and 100 percent below 2010 levels by 2050. Those targets are far more ambitious than what Colorado has adopted.

There is no doubt that more aggressive emissions reductions would cost sectors like the coal industry. Yet as the National Climate Assessment points out, inaction on climate change has substantial costs of its own, including negative public health impacts from extreme heat and ozone, energy costs from increased air conditioning, and property losses from wildfires and floods—not to mention the many impacts of earlier and reduced flows, warmer winters, and reduced snowpack.

When it comes to avoiding future warming, acting now could yield profound benefits by mid-century. On the Western Slope, the Aspen Global Change Institute projects that switching from the “high emissions” trajectory that the world is currently on to a “middle emissions” trajectory could cut projected end-of-century temperature increases by half. And in their 2017 paper on climate change and the Colorado River, Brad Udall and Jonathan Overpeck concluded that reducing emissions enough to lower future warming from 9.5 degrees Fahrenheit to 6.5 degrees could mean the difference between 40 percent less water in the Colorado River by century’s end and 25 percent less—neither of which is necessarily promising, but the improvement would make a difference.

“Every step we take today is a good step,” Udall says. “Often times these steps toward reducing emissions have enormous co-benefits, like cleaner air and less mercury in our air and water. In many cases, we save money by moving to a cleaner energy system. Many of these things we are already pursuing, just not fast enough. The longer we wait, the more harm we do, so why not push hard now, reap all these benefits, and save the climate?”

Print

Print