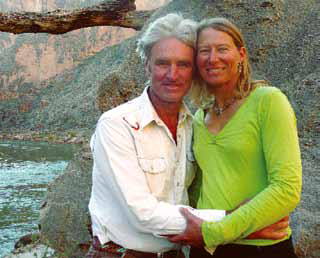

A couple works to protect an iconic river, and a local one

Float through the Grand Canyon with Andy Hutchinson and Kate Thompson and the journey would mimic that of environmentalists Edward Abbey and Martin Litton when they explored the canyon 40 years ago. Rather than motoring the world-famous stretch of the Colorado River in a few days, the couple guides groups in wooden dories.

Over the course of the two-week trip, they teach a wide range of subjects from river ecology to canyon geology to the evolution of boats used in the canyon. Both belong to the Grand Canyon River Guides, an association that works to protect river ecosystems and improve the guides’ lifestyle through healthcare and career counseling. From protecting freshwater springs to lobbying for more launch dates and getting signs posted at campsites, they work closely with the National Park Service on a wide array of issues. “It’s become a really nice dance we’ve done together,” Thompson says. “We consider ourselves stewards of the resources.”

The age of the river guides in the Grand Canyon surprises many, the couple says, but it’s a career, not a college job. “I think they expect 20-year-old yahoos,” says Hutchinson, a former U.S. competitive kayaker, but in reality, “Newbies are riding the shoulders of giants.”

Thompson began running rivers at age 18. Though she grew up on a farm in Maryland, the West always resonated as home. “I pretty much came out of the womb knowing that the West was my landscape,” she says.

Before she began professionally guiding trips down the Grand Canyon in 2002, Thompson worked as a soil and geologic researcher there for 13 years. Projects included studying archaeological and geologic sites and comparing before and after conditions resulting from the Glen Canyon Dam, which has interrupted the Colorado River’s flow 15 miles upstream since 1963. “It’s been a really nice marriage of bringing science to guests,” she says of her evolving career.

Hutchinson remembers the first time he saw a dory. It was October 1982 during a kayak trip down the Grand Canyon. While standing by an ancient Anasazi granary in Nankoweap at mile 53 of the trip, he saw several dories floating down the river. “I was smitten,” he says.

Each year the couple guides three or four trips through the Grand Canyon. The other 10 months they reside in Dolores, Colo., where Hutchinson builds dories and restores historical boats, a hobby turned profession when people began calling. Thompson runs a professional photography business and offers freelance graphic design in the wintertime.

“It’s a lifestyle of love,” Thompson says, noting that it’s enough to pay the bills, but, “We live very simply.”

When they’re not paddling their home river, the Dolores, they work on river enhancement projects as board members of the Greater Dolores Action Group. Creating river walks, bike trails and removing junk metal from the river are among some of the ventures the group has accomplished to help make boating and fishing safer.

Hutchinson remembers the Dolores’ pre-dam days. As a college student he wrote letters and attended meetings during the planning and development of McPhee Reservoir. The project’s 1977 Environmental Impact Statement said operators should attempt to maximize recreational and commercial rafting.

But Hutchinson says there is room for improvement, noting that dam officials don’t announce when they are planning a release-the only time the river is boatable-until the last minute. The Dolores Water Conservancy District updates release information weekly on its website, and a spill committee, composed of commercial and private rafters, irrigators and water managers, meets each winter to discuss the reservoir’s operating plan for the upcoming year. Such an effort is an example of a sea change Hutchinson has seen in the Bureau of Reclamation and among dam officials. People are beginning to listen to recreation’s advocates.

Hutchinson grew up in a ranching family in Colorado’s upper Arkansas Valley, where his ancestors moved to start a cattle ranch in the late 1860s after a bitter-cold winter prospecting in Leadville. Hutchinson’s niece currently runs the ranch. His father sat on the Upper Arkansas Water Conservancy District board, and Hutchinson remembers many discussions surrounding water politics. He has stood on both sides of the picket line.

While in his early 20s, Hutchinson worked as a guide on the Arkansas River. His parents asked him to attend a ribbon-cutting ceremony near Twin Lakes, where Hutchinson saw his fellow river guides protesting the water project. A decade later, he stood on the other side when he went to protest the Animas-La Plata water project.

Hutchinson will always have the ranch perspective, he says, but while he has a sympathetic ear, he’d rather keep water in rivers.

Print

Print