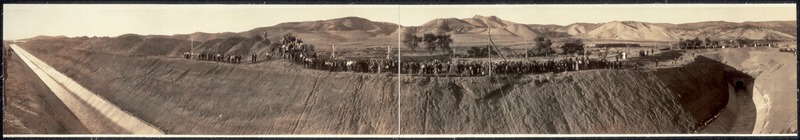

Official opening of the Gunnison Tunnel by President Taft at the west portal, Montrose, Colorado, September 23, 1909. Photo by Almeron Newman.

Before irrigated agriculture in the Uncompahgre and North Fork Valleys, there was chico brush. These woody desert plants covered vast swaths of land in southwestern Colorado until the late 1800s and early 1900s, when works like the Gunnison Tunnel diverted water that was used to transform these valleys into the agricultural hubs they are today—leaving chico brush on the dusty sidelines.

As water resources in the region have grown more stretched in recent decades, many stakeholders recognize the need to update operations to improve their odds in the face of future water scarcity. The Colorado River Compact of 1922 dictates that water from the Colorado River must be shared between seven Colorado River Basin states and Mexico. Further, this compact “obligates the upper basin states (Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming) to not not cause the flow of the river at Lee Ferry, Arizona to be depleted below 75 million acre feet over any period of 10 consecutive years,” according to the Citizen’s Guide to Colorado’s Interstate Compacts. So far, this obligation has always been met.

Lake Powell in Arizona. Photo by Wolfgang Staudt.

However, delivering this promised water may become much more difficult in the near future. Lake Mead and Lake Powell, two of the reservoirs that store water destined for lower basin states (Arizona, California, and Nevada) and Mexico, reached record low levels this year, highlighted by ominous bathtub rings in the lake sediments. This is indicative of how low the Colorado River has been recently due to steadily increasing demand for a variety of municipal, industrial, and agricultural uses. According to the Citizen’s Guide to Colorado Water Conservation, “the gap between water supply and demand for municipal and industrial uses alone could reach 560,000 acre feet by 2050 absent proactive measures…these future gaps in municipal and industrial water supply will likely be met by voluntary transfers of water out of irrigated agriculture, as lucrative offers are made by urban utilities and industrial operators.” If this economic pull were to slowly dry up agriculture in southwestern Colorado, it would deal a significant blow to the state’s economy and heritage, not to mention the cornucopia of delicious, Colorado-grown produce that we enjoy.

“If we don’t do something then other people are going to think we aren’t taking this seriously and then the water will be gone,” says Tom Kay, a farmer and co-owner of North Fork Organics. Without irrigation water to cultivate crops and the agricultural lifestyle in the valleys, irrigators fear that nothing will be left but chico brush.

That’s why some of those folks in the Uncompahgre and North Fork Valleys came together in 2010 to form No Chico Brush (NCB), a farmer- and rancher-led group of interested citizens who are working together to look at future water availability and irrigation efficiency. The group consists of an array of interests including county commissioners; water organizations; special interest groups like The Nature Conservancy and Trout Unlimited; citizens; and more , according to Steve Schrock, the coordinator of NCB.

John Harold holding a piece of the drip irrigation tape that gets laid in the field. Photo credit: © Mark Skalny for The Nature Conservancy, 2013. (All Internal Rights, Limited External)

With diverse interests come diverse objectives. “I wanted to find ways to educate and encourage farmers to understand that we have to modernize irrigation practices because of the pressures on water,” says John Harold, one of the farmers who brought the group together. NCB aims to keep their lands for agricultural purposes (and thus, free of chico brush) far into the future by implementing more efficient irrigation practices, which will also increase in-stream flows to benefit recreational economies and wildlife habitat. This will ensure that local communities, crops, and ecosystems continue to flourish, even in years when little water is available. It’s a natural partnership between environmental interests like Trout Unlimited and the Nature Conservancy and local farmers and ranchers. However, not all of the farmers and ranchers in NCB agree on the necessity of updating irrigation infrastructure, pointing out that the current system has worked well for over a century. Having a diverse range of opinions within the group has helped to more accurately represent community needs and interests.

“We don’t agree on everything but we have a lot of common goals,” says Aaron Derwingson with The Nature Conservancy. Given the sometimes unpleasant history between environmentalists and farmers, tensions were a bit high at first and the path toward partnership wasn’t easy. Despite their differences, these stakeholders do agree that working together is imperative. “(Collaboration) takes more time and more effort but for us it’s the only way we’re going to build a lasting conversation,” Derwingson says. “I think the main benefit is we can speak with a strong voice. People are going to listen to that more than any one of us individually.”

To facilitate greater adoption of water efficiency practices, the group is focusing on research on the Western Slope. Research has been done elsewhere in the state but NCB has emphasized the importance of collecting region-specific data. NCB partnered with Colorado State University and successfully acquired two grants that have helped fund this ongoing research

Sweet corn near Olathe, CO. Photo credit: © Mark Skalny for The Nature Conservancy, 2013. (All Internal Rights, Limited External)

Further irrigation efficiency financing has been hard to come by recently and current funding may not be enough to meet farmers’ needs in the future, Schrock says. However, some larger programs to incentivize the switch to more efficient irrigation systems are underway. In 2014, a group of municipal water providers throughout the Colorado River Basin, including Denver Water, partnered with the Bureau of Reclamation to address Colorado River water shortages and created the Colorado River System Conservation Program. This program has provided funding for water conservation pilot programs. One of these pilot programs is the Organic Transition Program, designed by Derwingson and Kay, which pays farmers to grow cover crops for three years, thereby using a third of the water they would otherwise. This also helps farmers get that land certified as organic, since one of the requirements is that the land “must not have had prohibited substances applied to it for the past three years.” Thus, farmers will save water and then be able to grow a higher value crop. “I’m looking for ways to help farmers expand their economic horizons and organic is a way to do that,” says Kay.

Fly fishing on the Gunnison River outside of Delta, Colorado. Photo credit: © Mark Skalny for The Nature Conservancy, 2013. (All Internal Rights, Limited External)

All of us have a lot to gain when Colorado farmers and ranchers shift toward more water-efficient systems. By conserving what they can now, they are doing their part to ensure the continuation of agriculture in southwestern Colorado and the overall prosperity of our state. “Agriculture is a huge part of our heritage, economy, and history. We (in NCB) are preserving agriculture. real farms, real farmers, and not having our agricultural economy move toward hobby ranches and farms or subdivisions,” says Schrock.

Check out this Trout Unlimited video for more insight on the work of No Chico Brush.

Learn more about efficient water use in agriculture by reading CFWE’s new Citizen’s Guide to Colorado Water Conservation, now available to flip through or order here.

Learn more about efficient water use in agriculture by reading CFWE’s new Citizen’s Guide to Colorado Water Conservation, now available to flip through or order here.

Print

Print

Reblogged this on Coyote Gulch.