“When it comes to the precipitation that falls in Colorado, we get what we get. But some are working off the hope that we can make new water appear out of thin air by forcing clouds to give up the goods,” wrote Josh McDaniel in an article for Headwaters Magazine– McDaniel was referring to cloud seeding. The topic was discussed last month at the Colorado Water Workshop in Gunnison and is again on our minds, thanks to an article published today in the High Country News Goat Blog. As the High Country News article describes,

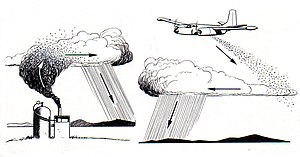

Making rain may seem a bit like alchemy, but the practice has been around since the 1940s, when engineers at General Electric began experimenting with dumping dry ice into clouds from airplanes. Water districts and ski resorts around the West got into the practice in the 1970s, shooting silver iodide into winter clouds from mountain-top cannons.

Silver iodide crystals behave like ice, attracting water droplets to them until they grow big enough to fall to the ground as snow. Cloud seeding advocates say the practice is inexpensive—$10-20 per acre-foot of water created—and can boost snowfall by 10 to 15 percent. They’re also quick to point out there are no documented negative environmental effects of the process.

The process is used by water districts in Southern California, Nevada and Arizona who pay states in the Upper Colorado River Basin to seed clouds. Since 2006, Lower Basin states have spent over $800,000 in Colorado and around $500,000 in Utah and Wyoming.

Out-of-state groups aren’t the only ones paying for Colorado cloud seeding. As McDaniel wrote,

Denver Water, the state’s largest utility, has employed the concept, gaining an estimated 35,000 to 50,000 acre feet of water annually, at a cost of $12 to $23 per acre

foot. The induced precipitation falls across about 6,000 to 7,000 square miles of watersheds that feed the agency’s reservoirs.

But not everyone is convinced that we’re seeing real results from cloud seeding. From Headwaters:

Nolan Doesken, Colorado’s State Climatologist, remains unconvinced. “The science of cloud seeding in the lab is rock solid, but the application is a little harder to

determine,” he says. “The underlying variability of precipitation in any one location makes it difficult to definitively conclude that the change you observe is directly related

to cloud seeding.”

Or, as stated in an Orion Magazine article,

Seventy years into an international experiment in weather modification, scientists still haven’t arrived at any consensus on whether or not the process works. We know that silver iodide mimics the crystalline structure of ice, and that when it’s injected into clouds – either by aircraft flying overhead, or on the ground generators that send up plumes of vapor, or, in the case of China, by decades old artillery – the chemical forms small ice nuclei in the clouds, and additional moisture gloms onto the crystals. Once the crystals are large enough or heavy enough, they fall from the cloud. Yet weather patterns are so variable that’s it hard for scientists to know when to attribute precipitation to cloud seeding.

Still, ski resorts and others pursue it. What do you think?

Related articles

- Cloud Seeding Not Really An Option During Wildfire Season (denver.cbslocal.com)

- Idaho Power Reports Increased Snowpack After Seeding Clouds (boiseweekly.com)

- Cloud-Seeding: Why Can’t We Just End The Drought Ourselves? (stlouis.cbslocal.com)

- Modifying Weather In The Colorado River Basin (cloverleafsky.wordpress.com)

- Could Laser Beams Induce Rain? (news.discovery.com)

Print

Print