Colorado will launch a far-reaching $20 million conservation planning effort this spring designed to ensure the state can reduce water use enough to stave off a crisis in the drought-choked Colorado River Basin.

The money, likely to be spent over a period of two to three years, will pay for a major public, consensus-based initiative to determine how to equitably set aside enough water to protect Colorado’s share of the river and how to pay farmers and potentially cities to reduce their use.

The river is critical to Colorado’s water supply, with roughly half of the supplies for the Denver metro area coming from its annual flows and even larger amounts fueling the state’s farms.

The initiative will include at least seven technical and public work groups examining the legal, economic, and environmental issues inherent in such a demand management program, according to Brent Newman, head of the Interstate and Federal water section of the Colorado Water Conservation Board (CWCB). Demand management is the term water officials use to describe water conservation. It will also include a feasibility study and several pilot programs.

State staffers expect the work to take more than a year to complete as they iron out whether and where to cut back use, how to measure those reductions, and how to protect the environment, local economies, and the legal rights of water users while the program is in effect.

“We’re going to do this one bite at a time,” Newman said. “It’s not something that can be slammed together.”

Water users on both the West Slope and Front Range are gearing up for the project, hopeful that a proactive conservation program will provide a sort of insurance policy should a full-blown crisis erupt on the river.

“We’re pretty anxious,” said Brad Wind, general manager of the Berthoud-based Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District, which manages the Colorado-Big Thompson Project. The project diverts Colorado River water from the West Slope for farmers and cities on the Northern Front Range. “We realize it’s going to take some time, but we would feel better having a little insurance than having nothing and having everything implode.”

Seven states comprise the Colorado River Basin, with Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming forming the Upper Basin and Arizona, Nevada and California making up the Lower Basin.

Last October, after nearly four years of work, the seven states agreed to a broad, preliminary set of drought guidelines, known as the DCP, or drought contingency plan, that begin to spell out how cutbacks will occur on the river.

Under those agreements, Colorado and its Upper Basin neighbors could set aside up to 500,000 acre-feet of water in a special drought pool in Lake Powell. That’s enough water to serve roughly 1 million homes for a year.

In addition, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation will be allowed to release up to 1 million acre-feet of water from three Upper Basin state reservoirs that, together with Powell, are part of the Colorado River Storage Project, to boost storage in Lake Powell if it reaches critical lows. Two of those are located at least partially in Colorado.

How much time Colorado and the other states have to refine these drought plans and put them into action isn’t clear yet.

On Feb. 1, after California and Arizona failed to hit a federal deadline for finishing their drought plans, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation said it was moving forward to impose its own water-saving plan on the region.

Reclamation Commissioner Brenda Burman said she would halt that federal initiative only if Arizona and California complete their work by March 4. If that deadline isn’t met, the states may have to incorporate the federal government’s directives into their own work.

Equally concerning is the weather.

The drought has pushed Lake Powell and Lake Mead, the river’s two primary storage buckets, to critical lows. If the region endures another year as desperately dry as 2018, Lake Powell’s ability to produce hydropower, the major source of revenue for complying with the Endangered Species Act, could be in jeopardy. If utilities don’t have the money to comply with the ESA, the federal government can shut down their water diversions, as it has done in the past in places such as the Klamath Basin in Oregon in 2001.

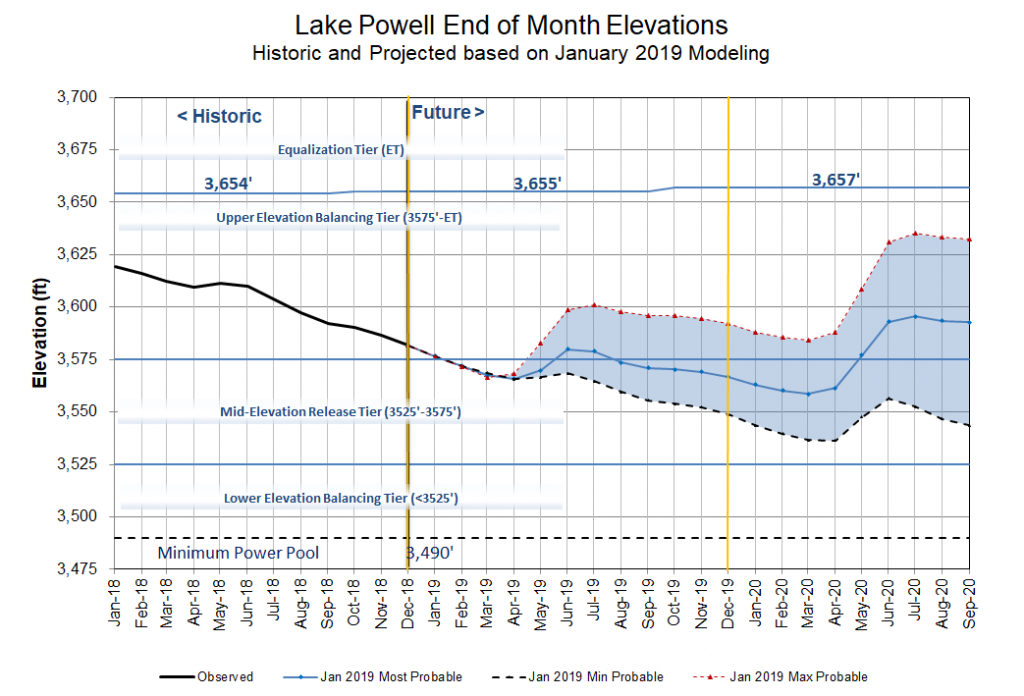

Even though early snows have helped boost mountain snowpacks across the region, they aren’t likely to be deep enough to pull the region back from the brink of a major water crisis. Inflows into Lake Powell this year, for instance, are projected to be just 64 percent of average, according to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, well below the super-sized numbers needed for it to begin to refill.

At that rate, by August of this year, Powell will be shockingly close — within about 81 feet — of hitting its minimum power pool, a level it flirted with in 2012 and 2013, according to Heather Patno, a hydrologist with the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation in Salt Lake City.

In the Lower Basin, Lake Mead is already so low that Arizona is facing mandatory water cutbacks this year.

“We need as much time and space to craft and sharpen these tools as we can get,” said James Eklund, Colorado’s representative on the Upper Colorado River Commission. “Knock on wood we’ll get a reprieve from the hydrology for a while.”

If not, Newman said that the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation may release water from the Colorado River Storage Project reservoirs in Utah, Wyoming and Colorado to boost levels in Powell, giving Colorado and other states more time to figure out how to execute these unprecedented conservation measures.

Water users across the state are closely watching this new water-saving initiative, with farm interests on the West Slope and out on the Eastern Plains intent on ensuring that any water cutbacks that may occur are done only on a paid, voluntary basis and that all water users shoulder the reductions equally.

At the same time large urban water users, most of whom have less favorable water rights than the state’s farmers do, want to ensure their municipal supplies aren’t radically reduced.

“We are at a point where the Upper Basin does have some time to get this demand management right,” said Andy Mueller, general manager of the Glenwood Springs-based Colorado River Water Conservation District. Looking for ways to reduce water use, he said at a meeting of the Colorado Water Congress earlier this month, “is an incredibly threatening concept to West Slope water users. But the River District is committed to proactively engaging and working with the CWCB to figure out how we can stand a program up that truly protects all of us.”

A clearer outline of the state’s approach to developing the demand management initiative will be presented at a meeting of the CWCB March 20-21. Depending on the outcome of that meeting, the various task forces could begin work in April or May, Newman said.

Jerd Smith is editor of Fresh Water News. She can be reached at 720-398-6474, via email at jerd@wateredco.org or @jerd_smith.

Fresh Water News is an independent, non-partisan news initiative of Water Education Colorado. WEco is funded by multiple donors. Our editorial policy and donor list can be viewed here.

Print

Print