Early winter storms that have blanketed the state this year have delivered snowpacks that are nearly 90 percent higher than they were last year at this time, a startling statistic given Colorado’s ongoing battle with a drought that just can’t seem to call it quits.

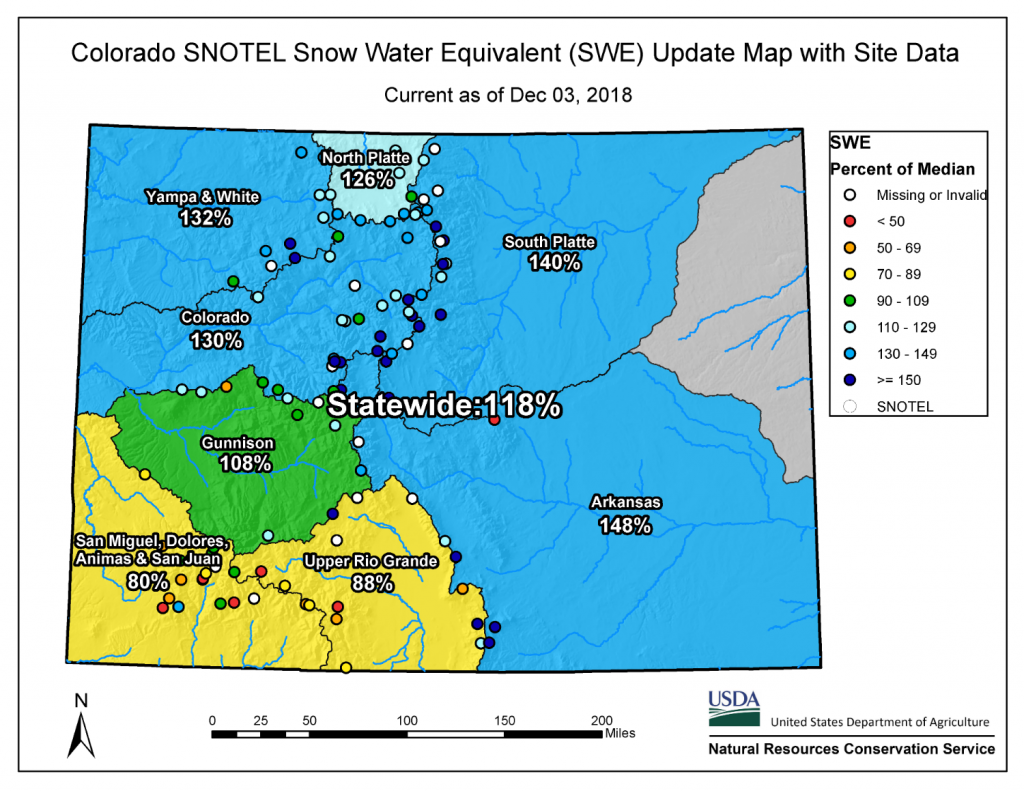

Statewide, as of Dec. 3, snowpack stood at 118 percent of normal, up from 63 percent at the same time last year, an 87 percent jump in the benchmark, according to the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NCRS) in Lakewood.

Snowpack readings in the South Platte Basin, which includes the Denver metro area and most of the northern Front Range, stood at 140 percent of average as of Dec. 3, up from 80 percent last year, according to the NRCS.

And the Arkansas Basin, stretching from Leadville down to the very southeastern corner of the state, stood at 148 percent of average, up from 63 percent last year.

“It’s a much better start,” said Brian Domonkos, snow survey supervisor for the NRCS. “However, it’s very early in the year. And as dry as it was last year, it would be good to have a little more. We definitely want to make up for last year’s deficits.”

The only regions that have yet to hit the above-average mark are the San Miguel, Dolores, Animas and San Juan river basins, which include Durango, and the Rio Grande Basin, which includes Alamosa.

“Those southern basins are still below normal,” Domonkos said. “That’s not a surprise, given that October was a normal month for them in terms of precipitation. That’s not enough to make up [for last year’s dry weather].”

The snow has given drought watchers across the state a much-needed breather after a summer of desperately dry weather, dozens of 90-plus degree days, and a nearly record-breaking fire season.

Thanks to the early storms, Wolf Creek Ski Area opened Oct. 13, its second-earliest open date ever, and this year it was the first ski country in the nation to welcome skiers, according to Heather Dutton, who represents the Rio Grande Basin on the Colorado Water Conservation Board.

Whether this year delivers enough snow to refill reservoirs and lift the state out of its drought is far from clear.

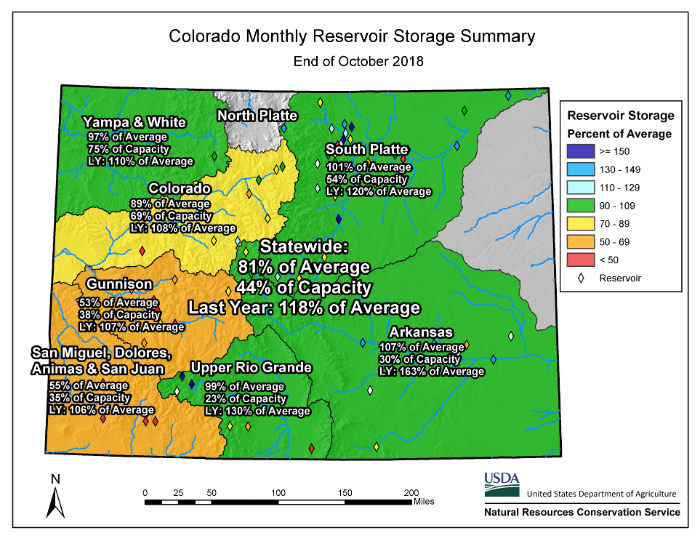

Going into last year’s irrigation season, the state’s reservoirs were largely full, but the summer of 2018 saw them drained as farmers and thirsty urbanites ran sprinklers and turned on their taps to compensate for the dry weather. At the end of what’s known as the water year, Oct. 31, statewide reservoirs stood at just 81 percent of average, well below the previous year’s mark of 118 percent of average.

“Reservoirs took it on the chin this summer,” said Peter Goble, a drought specialist and climate scientist with the Colorado Climate Center.

In the south-central part of the state, though the snow and fall rains provided some relief, reservoirs stood at just 23 percent of capacity in the Rio Grande as of Oct. 31, the worst reading in the state, according to the NCRS.

Among the most stressed is Colorado’s largest storage pool, Blue Mesa Reservoir, near Gunnison. It nearly emptied this summer, and reached its lowest point in 30 years this fall.

Colorado’s parched condition is the primary reason much of the state remains classified as being in extreme or exceptional drought by the U.S. Drought Monitor.

“We are far ahead, but having an early season snowpack does not mean we have solved the problem,” said Brent Bernard, a hydrologist at the Colorado River Basin Forecast Center in Salt Lake City. “We need to end this season in July with way above average snowfall. Right now people think, ‘Oh, it’s cold, everything is fine.’ But it’s not.”

Jerd Smith is editor of Fresh Water News. She can be reached at 720-398-6474, via email at jerd@wateredco.org or @jerd_smith.

Fresh Water News is an independent, non-partisan news initiative of Water Education Colorado. WEco is funded by multiple donors. Our editorial policy and donor list can be viewed here.

Print

Print