Denver Water and three other organizations are seeking to overturn a state order that directs Denver to adopt a strict new treatment protocol preventing lead contamination in drinking water.

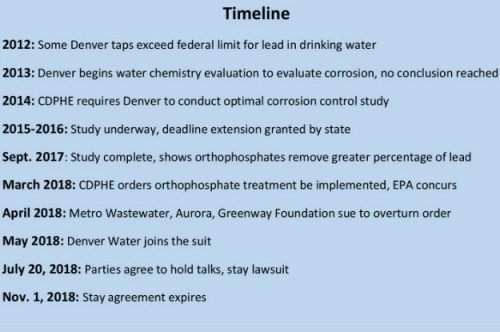

Denver is not in violation of the federal law that governs lead, but it has been required to monitor and test its system regularly since 2012 after lead was discovered in a small sample of water at some of its customers’ taps.

In March of this year, after Denver completed a series of required tests and studies, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE) ordered the utility to implement a treatment protocol that involves adding phosphates to its system. It has until March of 2020 to implement the new process.

Denver, which serves 1.4 million people in the metro area, has proposed instead using an approach that balances the PH levels in its treated water and expands a program replacing lead service lines in the city. Old lead service lines are a common source of lead in drinking water.

Treating lead and copper in water systems is a complex undertaking governed by the federal Lead and Copper Rule. In Denver, for instance, there is no lead in the water supply when it leaves the treatment plant. But it can leach into the supply via corrosion as water passes through lead delivery lines and pipes in older homes. Denver has 58,000 lead service lines in its system. Lead has continued to appear in samples it has taken at some customers’ taps, according to court filings, though not at levels that would constitute a violation of the federal law.

Eighty-six samples taken since 2013 have exceeded 15 micrograms per liter, including one tap sample which measured more than 400 micrograms per liter, according to court filings. The 15-microgram-per-liter benchmark is the level at which utilities must take action, including public education, corrosion studies, additional sampling and possible removal of lead service lines.

In response to the state’s order, the City of Aurora, the Metro Wastewater Reclamation District and the nonprofit Greenway Foundation, which works to protect the South Platte River, sued to overturn it, concerned that additional phosphates will hamper their ability to meet their own water treatment requirements while also hurting water quality in the South Platte. Denver joined the suit in May.

Because Denver Water services numerous other water providers in the metro area and participates in a major South Metro reuse project known as WISE, short for Water Infrastructure and Supply Efficiency, anything that changes the chemical profile of its water affects dozens of communities and the river itself.

Among the plaintiffs’ concerns is that phosphate levels in water that is discharged to the river have to be tightly controlled under provisions of the Clean Water Act. If phosphate levels in domestic water rise, wastewater treatment protocols would have to be changed, potentially costing hundreds of thousands of dollars, if not more, according to a report by the Denver-based, nonpartisan Water Research Foundation.

From an environmental perspective, any increased phosphate in the South Platte River would make fighting such things as algae blooms, which are fueled by nutrients including phosphorous, much more difficult and could make the river less habitable for fish.

But in its statement to the court, the CDPHE said the state’s first job is to protect the health of the thousands of children served by Denver Water in the metro area.

“The addition of orthophosphate will reduce lead at consumers’ taps by approximately 74 percent, as opposed to the cheaper treatment favored by plaintiffs [PH/Alkalinity], which will only reduce levels by less than 50 percent,” CDPHE said in court documents. “This is a significant and important public health difference, particularly because there is no safe level of lead in blood…Even at low levels, a child’s exposure to lead can be harmful.”

How much either treatment may eventually cost Denver Water and others isn’t clear yet, according to state health officials, because it will depend in part on how each process is implemented.

Denver, Aurora and Metro Wastewater declined to comment for this story, citing the pending lawsuit.

The Greenway Foundation did not respond to a request for comment.

In late July, all parties agreed to pause the legal proceedings while they examine water treatment issues as well as the environmental concerns raised by higher levels of phosphorous in Denver Water’s treated water supplies. If a settlement can’t be reached by Nov. 1, the lawsuit will proceed.

Jonathan Cuppett, a research manager at the Water Research Foundation, said other utilities across the country may be asked to re-evaluate their own corrosion control systems under a rewrite of the Lead and Copper Rule underway now at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The newly proposed federal rule is due out for review later this year or by mid-2019.

Cuppett said the changes may lean toward more phosphate-based treatment for lead contamination. In fact, the EPA issued a statement in March in support of the CDPHE’s order to Denver Water.

“Within the [Lead and Copper Rule] there are a variety of changes that may be made. Depending on what those changes are other utilities may have to evaluate their strategy again or more frequently. And if that is the case, we may see more of this issue where someone is pushing for phosphorous for control for public health, creating a conflict of interest with environmental concerns,” Cuppett said.

Colorado public health officials said they’re hopeful an agreement can be reached, but that they have few options under the federal Safe Water Drinking Act’s Lead and Copper Rule.

“The [Lead and Copper Rule] is a very prescriptive, strict rule,” said Megan Parish, an attorney and policy adviser to CDPHE. “It doesn’t give us a lot of discretion to consider things that Metro Wastewater would have liked us to consider.”

Jerd Smith is editor of Fresh Water News. She can be reached at 720-398-6474, via email at jerd@wateredco.org or @jerd_smith. Fresh Water News is an independent, non-partisan news initiative of Water Education Colorado. Our editorial policy can be viewed here.

Print

Print