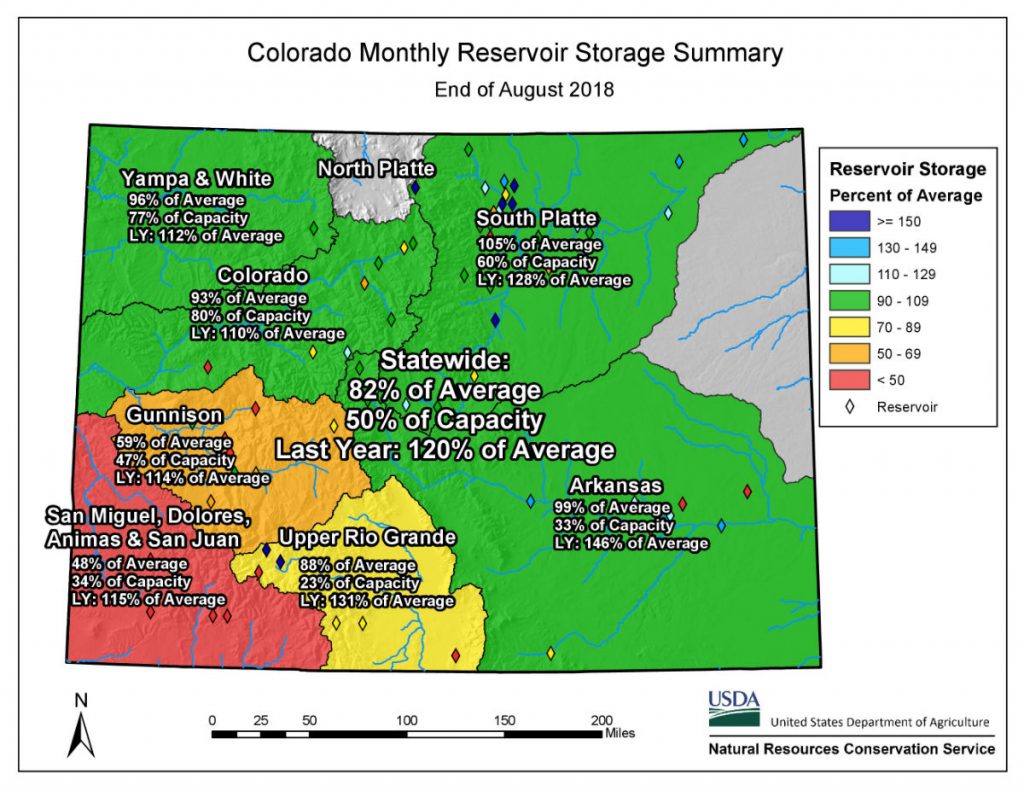

After a summer of blazing 90-plus degree days and weeks without rain, Colorado’s water reservoirs, the critical storage systems designed to get us through dry times, are just half full on average, and in southwestern parts of the state they are far lower.

“We’re seeing a record decline in storage because it’s been so hot,” said Taryn Finnessey, chair of the state’s Water Availability Task Force.

Precipitation is tracked from Oct. 1 through Sept. 30 each year in a measure known as a water year. And the 2018 water year is on track to be the state’s second driest on record, with the seared 2002 drought year continuing to hold that distinction, according to Brian Domonkos, snow survey supervisor for the Natural Resources Conservation Service. Domonkos and his team are responsible for tracking snowfall and rain across Colorado.

State officials activated a drought response plan in May covering 34 counties in the southwestern part of the state. The activation gives farmers and others access to various relief programs, such as low-interest loans, and triggers a coordinated monitoring program among state agencies charged with helping those hurt by the dry weather.

Because summer rains have done little but tamp down the dust, Finnessey said Colorado will keep its drought plan activated through the winter and, in fact, may expand it to six counties in northwestern Colorado, including three in the heart of Colorado ski country. Newly added counties are likely to include Pitkin, Eagle, Summit, Grand, Moffat and Routt.

Northwestern Colorado, home to the Yampa River, has been historically dry and hot this summer. Once known for its legendary, generous streamflows, the Yampa for the first time ever saw water use curtailed as flows tanked in the face of the relentless heat.

For days in Steamboat Springs, Division Engineer Erin Light, the top water regulator on the Yampa, carefully monitored stream gauges, knowing that big diversions were scheduled to occur that would completely dry up the waterway. The practice is known as sweeping the stream.

She and her staff started driving the river daily to monitor how bad it was. Finally, after seeing long stretches of dusty riverbed, she made the decision Sept. 5 to order water use cut back, placing what’s known as a call on the mainstem of the river for the first time in history.

Light said it was an educational moment for ranchers and other water users who’ve long been accustomed to a Yampa River that faithfully delivered whatever they needed. “They thought they were call-proof,” Light said.

The Front Range and parts of the Eastern Plains have had more water than the rest of the state, although the hot temps have taken a toll. Denver Water said in a statement that its storage reservoirs are 85 percent full. Normally they would be 91 percent full after a summer of lawn watering.

Farther south and west in the Gunnison River Basin more bad-news water records are being set almost every week. With just over two weeks remaining until the official water year ends Sept. 30, the scenic region, home to the Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park, is on track to see its driest year in history, according to NRCS’s Domonkos. Right now it’s below the record dry mark set, again in 2002, and if the region doesn’t get 3.5 inches of additional rain by the end of the month, 2018 will claim the driest-year-in-the-Gunnison title, according to Domonkos.

It’s not just the scorched summer that has state water officials worried, however. Those who track the seven-state Colorado River Basin, which includes Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, Arizona and California, are seeing worrisome new patterns develop.

Flows in the river declined 16.5 percent between 1916 and 2014, according to a new study released last week.

“About half of this decline is due to increasing temps, and the other half is due to patterns in where the precipitation falls,” said Brad Udall, a scientist and scholar with the Colorado Water Institute at Colorado State University and one of the study’s authors.

“Precipitation has moved from the highly productive basins in Colorado to these less effective basins in Utah’s deserts, where it doesn’t do a good job of showing up in the river,” Udall said.

Looking ahead to the coming winter, climate experts say there is a roughly 70 percent chance that an El Niño weather pattern will develop. If it arrives, it should deliver much-needed moisture to Arizona and New Mexico and possibly Colorado’s hard-hit San Juan Mountains in the state’s southwestern corner. But how much moisture will fall farther north isn’t clear yet.

Peter Goble is a climatologist and drought specialist with CSU’s Colorado Climate Center.

“The El Niño is definitely developing so we’re hoping for better snowpack numbers this year, but we won’t get excited until we see more of these El Niño patterns develop in late October or early November,” Goble said.

And what everyone would like to see is a return to something that more closely resembles normal. For the state to claw its way back to average before the end of this year would require 11 inches of rain on average to fall statewide before Sept. 30, according to Domonkos.

Is that likely? Not really, he says. The month of September delivers 2 inches on average. In a more normal weather year, Colorado would receive just 16 inches of precipitation for the entire year.

CSU’s Goble says this year delivered a surprising one-two punch – first came the ultra-light snowpack and then a summer of super-hot temperatures. He and others are grateful that the state came into the year with reservoirs brimming with water thanks to the big snows of 2017.

But if 2019 delivers another river-busting dry spell, one in which the stressed reservoir system can’t recoup its supplies, the damage from this drought will grow dramatically.

“Because we went into this water year with good storage, people have been getting by even though it’s been difficult,” said Kevin Rein, the state engineer and Colorado’s chief water regulator. “If we have another winter and spring like 2018, it will be very bad.”

Jerd Smith is editor of Fresh Water News. She can be reached at 720-398-6474, via email at jerd@wateredco.org or @jerd_smith.

Fresh Water News is an independent, non-partisan news initiative of Water Education Colorado. WEco is funded by multiple donors. Our editorial policy and donor list can be viewed here.

Print

Print