The San Luis Valley’s Race to Rebalance its Overdrawn Groundwater Supply

Early on a March morning, high above the floor of the San Luis Valley, pale blue skies are just gaining light and the glamorous white peaks of the Sangre de Cristo and San Juan mountains form an elegant, fluted rim around the top of one of Colorado’s most productive farm regions.

Far below on the flats, it is a typical, early spring workday. Farm trucks roll up and down Highway 160 between Monte Vista and Alamosa, gas stations and seed stores open for business, and dozens of potato warehouse workers report for duty. This is big farm country, where the hard work of cultivating potatoes, barley, alfalfa, carrots and lettuce is done by people whose hands are rough and who wear uniforms of insulated coveralls and heavy work boots.

Rich in culture, this closely knit community of 50,000 people is locked in a fierce internal struggle over how to save itself from a historic water crisis. If left unresolved, the crisis could force state regulators to shut down hundreds of irrigation wells, crippling the valley’s robust farm economy.

Workers check freshly cut seed potatoes before planting near Center, Colo.

At issue is an aquifer so stressed by overuse and chronic drought that it is in a virtual free fall. Since local water managers started monitoring in 1976, groundwater storage has dropped 1.2 million acre feet in the unconfined aquifer of the valley’s closed basin region. Some irrigation wells are so hampered by the aquifer’s decline that they can no longer pump, many surface water users with senior rights are being short-changed, and high commodity prices are making it difficult to convince people who still have adequate water to cut back their water use. “It really is a perfect storm,” says Steve Vandiver, general manager of the Rio Grande Water Conservation District, the local water agency that monitors groundwater levels and is now charged with raising them.

Similar crises have played out in Colorado’s South Platte Basin, on the Front Range, as well as the Arkansas Basin, in southeastern Colorado. In those instances, the state ultimately did shut down wells because the pumping was reducing surface flows in the rivers that others relied on. Thousands of acres of farmland are now dry.

Guardians of the San Luis Valley—including ranchers and farmers whose families have been here since the 1850s—are racing to keep that from happening here. Working from a plan first conceived by local potato farmer and water leader Ray Wright before his death in 2010, the local water community has developed an innovative framework of self-governance, including levying assessments on irrigated land, imposing fees to pump wells and providing payments to fallow ground. But after nearly 10 years of legal and regulatory battles, much of the hard work needed to bring the aquifer back into balance has yet to occur.

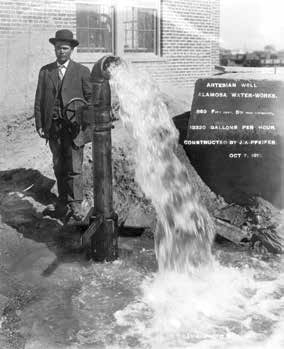

An 863-foot deep artesian well tapped by the Alamosa Water Works in October 1911 discharged 13,320 gallons per hour (left) with J. A. Pfeifer, well constructor, thought to be standing alongside. Photo courtesy of: Western History Collection, Denver Public Library

And time is short. In 2004, the state legislature directed the State Engineer’s Office to regulate San Luis Valley groundwater use in such a way as to maintain a sustainable water supply while protecting senior surface water users. State Engineer Dick Wolfe in turn has given the Rio Grande Water Conservation District until 2032 to stabilize the unconfined aquifer in the most heavilyimpacted area, meaning the amount of water flowing in equals the amount leaving. The district must also implement annual water replacement plans to offset impacts of well pumping to senior surface water rights.

After one year of implementing the first of six planned groundwater management subdistricts, there has been no physical improvement in the unconfined aquifer. Most believe the state will intervene and start shutting down wells if progress isn’t shown within the next three years, according to Vandiver. In the meantime, up to two additional subdistricts with their own groundwater management plans are being evaluated outside of the Rio Grande Water Conservation District’s boundaries, and Wolfe is developing pumping rules and regulations to have at-the-ready if any subdistrict plan is unsuccessful at protecting surface water users with senior rights.

Everywhere people are worried and impatient. “We should have been trying to get the aquifer into balance all along,” says James Ehrlich, executive director of the Monte Vista-based Colorado Potato Administrative Committee. “But it’s not as simple as it seems.”

Aquifers in Decline

Behind the court cases and regulatory delays is a complex set of hydrologic and geologic formations that scientists have spent years working to analyze and document. These include a pair of stacked underground aquifers, which serve as the primary source of water for the highest value crops: potatoes, barley and alfalfa.

Bureau of Reclamation general manager Steve Vandiver examines the Mumm Well, and artesian water source used to seasonally recharge wetlands in the Alamosa National Wildlife Refuge. Photo By: Kevin Moloney

The San Luis Valley is one of the highest altitude agricultural regions in the world—the highest in the United States. Semi-arid, with just 7 to 8 inches of average precipitation annually on the valley floor, it is dependent on snowpack from the surrounding mountains for river flows. Its cool nights and dry climate minimize disease and pests—and make it an ideal growing region.

By the early 1900s, however, all available surface water in the valley was claimed, first by Hispanic, and later European, settlers, who battled the Ute Indians for a chance to farm along the banks of the region’s rivers starting in the 1850s. Though little was known then about the unique hydrologic formations that lay beneath the fields, farmers had springs that literally bubbled to the surface. When the Dust Bowl struck in the 1930s, they began drilling wells to tap those artesian springs.

As hydrological science advanced in the mid-1900s, engineers and state water regulators came to understand that a second “confined” aquifer lay below the upper water formation. A layer of clay separates the two aquifers, and wells were drilled into the confined aquifer as well. The connection between the two aquifers is still not well understood, although it’s believed that the confined aquifer recharges itself at a much slower rate than its upstairs neighbor. Some, but not all, of the water pumped from these aquifers is tributary to nearby surface streams and must be replenished to keep senior surface water users from being harmed. But the relationship between pumping and depletions to the river is not one-to-one and remains much less clear than in places such as the South Platte and Arkansas basins.

The region’s unique hydrology doesn’t end there. The valley is also home to a large “closed basin,” a sprawling, fertile area where the Rio Grande and its tributaries deliver water each year through ditches, but from which no water returns to the river farther downstream,

as it does in almost every other river system in the state. Those return flows are critical to downstream users. To keep senior water right users in the lower valley from being harmed, and to ensure Colorado could meet its obligations to New Mexico and Texas under the Rio Grande Compact of 1938, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation spent much of the 1980s and ‘90s building the Closed Basin Project. It consists of a series of well fields that pump water from the closed basin into a set of canal systems, creating artificial return flows to the Rio Grande. The project continues today, moving an average of 17,000 acre feet out of the closed basin into the Rio Grande each year to partially replace depletions in the river.

From the 1930s through the 1970s, encouraged by the state and the seemingly endless supply of groundwater, farmers and ranchers drilled nearly 6,000 wells in the valley, helping create the third largest potato-growing region in the nation, and hearty barley, alfalfa and lettuce crops as well. Of those, 3,400 were drilled into the unconfined aquifer within the closed basin. “The State Engineer allowed people to drill wells whether they had surface [water] rights or not,” says Colorado Agriculture Commissioner John Salazar, a valley native. “That was a huge mistake, but at the same time it provided a huge economic benefit to the valley.”

With up to 600,000 acres of irrigated land, the valley now has nearly the same number of active irrigation wells—about 4,500—as the much larger South Platte Basin, which has 900,000 acres of irrigated land and over 5,000 active wells. The South Platte boasts the state’s largest agricultural economy, with a market value of $3.2 billion, while the San Luis Valley’s is approximately $475 million, according to Tom Lipetzky, director of marketing programs at the Colorado Department of Agriculture.

In 1972, the state sharply curtailed drilling of new wells in the confined aquifer and the alluvial aquifers in the valley, and in 1976 the Rio Grande Water Conservation District began formally monitoring groundwater levels. In 1981, a moratorium was placed on drilling wells in the unconfined aquifer of the closed basin area as well.

By the 1970s, the practice of recharging the unconfined aquifer using surface water supplies from the river had also expanded, with irrigators filling large holding ponds where water could slowly seep underground to supply their wells. Thanks to abundant snowfall throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the aquifer, though lower, continued to function as a renewable water supply. That peaceful period ended abruptly in 2002 when a record-breaking drought struck, robbing the Rio Grande and its tributaries of the plentiful water that Mother Nature and the irrigators had used to keep the aquifer balanced. In less than 18 months, groundwater levels plummeted 650,000 acre feet, a shocking change no one had ever witnessed. Less dramatic declines began again in 2010, accelerating in 2011 and 2012 for a total loss of another 450,000 acre feet. “It just fell out from underneath us,” Vandiver says.

The fragility of the aquifer was plain to see. Still high levels of pumping continued so that farmers could continue to cultivate, despite the drought.

Race to Recharge

Unlike the South Platte and the Arkansas basins, the San Luis Valley is almost totally reliant on agriculture for jobs and income. The valley is one of the poorest regions in Colorado, with per capita income of $18,396, well below the state average of $30,151. Farmers who can make $126,000 per quarter section growing barley for MillerCoors cannot afford to accept, say, $28,000 for a season of fallowing that land. For potato growers, that margin leaps upward; in a good year, they can make as much as $500,000 on a quarter section, which is 160 acres. “It’s easy for me to sit back and say this guy should pump less water, but he has to make a living,” says Ehrlich. “And not everyone is in a situation where they can afford to pump less water.”

The San Luis Valley began a large-scale transition from flood irrigation to center pivot sprinkers in the 1950s—and became increasingly dependent on groundwater in the process.

And yet, they may have to. In 2012, the initial phase of the Rio Grande Water Conservation District’s first subdistrict groundwater management plan was put into action. Subdistrict No. 1, which encompasses 179,000 acres in the closed basin, spent $1.2 million to buy 5,006 acre feet of stored surface water that was released into the river to offset well pumping. It also convinced its members to fallow 8,400 acres of land and reduce pumping by 20 percent. Despite those efforts, the aquifer fell another 123,000 acre feet.

Drought isn’t the only problem. Court battles have also delayed the subdistricts repeatedly, with one case reaching the Colorado Supreme Court in 2011. While most objectors to the subdistrict plan are now reconciled to the need for it, a small group of farmers, led by long-time valley resident Kelly Sowards, continue to challenge the subdistricts in court.

Sowards, who lives and farms in Manassa, leads a group known as the San Antonio, Los Pinos and Conejos River Acequia Preservation Association. They recently asked the court to throw out a key part of the Rio Grande Water Conservation District’s “Plan of Water Management,” which calls for a portion of the Closed Basin Project water to be reallocated and used to augment three reaches of the Rio Grande so farmers in Subdistrict No. 1 can continue to pump. But Sowards is adamant that the reallocation of that water violates the law and will continue to harm his surface water rights, which date to 1855.

The court decided in favor of the subdistrict on April 11, 2013, finding it appropriate to use Closed Basin Project water for replacing well depletions. If Sowards’ group had been successful in court, Vandiver says it would have derailed the subdistricts again because they would have been forced to find and purchase new—and extremely scarce— surface water in the basin. Still, Sowards says he and his fellow farmers in the south part of the valley feel they have no choice but to fight on. “A lot of folks don’t want much to do with me anymore,” he says. “And I’m sorry about that. I’m not a devil, but I want fair play.”

Also holding the subdistricts back are updates to a crucial groundwater model—needed to accurately calculate how much water must be repaid to the river to offset pumping from the aquifer each year—which are not yet complete. In the meantime, roughly half the wells in the valley can’t be regulated, delaying the formation of the remaining five subdistricts and hampering efforts to engage farmers valley-wide in the effort to save the aquifers.

Mike Sullivan, deputy state engineer of the Colorado Division of Water Resources, is overseeing work on the model. He says the state has been diligent, but it has been slowed by the complex hydrology, the court cases, and the need for better data. State regulators had forced irrigators to begin metering all the wells in the valley in 2007, measuring the water withdrawn. “In Subdistrict No. 1, we had lots of science and lots of measurements. We looked at the numbers and compared them with our model, and the numbers made sense. They matched the meter readings,” Sullivan explains.

Though the numbers calculated by the model for Subdistrict No. 1 matched the meter readings, they didn’t line up as well in other parts of the valley. The state went back to work, gathering more data and revising the modeling tool. Sullivan’s staff reviewed every satellite photo available from the past 25 years to estimate what the consumption would have been on each parcel. “We did not want to hand somebody an estimate that they were pumping 30,000 acre feet of water when the metering showed they were actually pumping 20,000 acre feet,” Sullivan says. “We’ve spent time trying to get the numbers right, both for pumping and the depletions that need to be replaced. I think we’re close.” The state anticipates delivering the model runs in June 2013.

Sam Vance, vice president of Conejos County Water Conservancy District, is among dozens of people who are anxious to see what the model will tell the growers. Vance’s land lies in what will become Subdistrict No. 3 in Conejos County. He says most of his district’s issues with the new management approach have been resolved, but it’s been difficult. “The problem is that as we start to develop technology, people get jealous and they think someone else is getting a better deal,” Vance says.

Across the valley, there are large variations in the water levels in the aquifer, and it’s become clear that some farmers will have enough water to continue farming while others will have to cut back dramatically. It all depends on location, whether they have surface water rights to offset their pumping, and what the modeling ultimately shows about connections between surface flows and groundwater. “Our position is that we support the science that develops through the model,” says Vance. “If the impacts [to the river] are coming through the wells, and some of it is, then we are going to have to deal with that. I’m not minimizing anyone’s injury. But at the end of the day, we have to let the science dictate what’s going to happen, and we have to be as fair as we can be.”

Enduring Economically

The U.S. Department of Agriculture has approved $120 million to help pay farmers in Subdistrict No. 1 to stop planting through a program known as the Conservation Resource Enhancement Program (CREP). The goal is to idle at least 40,000 acres of land in Subdistrict No. 1. Elsewhere across the valley, Vandiver expects an additional 40,000 acres to be fallowed, but that number may vary as pumping effects on various streams are further evaluated.

John Salazar, along with his brother LeRoy Salazar, who farms, is a long-standing rancher in the southern part of the valley. He has worked closely with the U.S. Department of Agriculture to get the CREP plan authorized, though the Salazar family lands lie far south of the areas where the CREP program will be implemented.

Farm manager Doug Messick works on a tempermental center pivot sprinkler on Lynn McCullough’s potato farm near Center, Colo. Photo By: Kevin Moloney

According to Salazar, the CREP program will help farmers who choose to transition out of farming by providing annual payments of $175 per acre over a 10- to 15-year period. Subdistrict No. 1 may offer additional bonus payments for CREP sign-up in specific areas. Whether enough farmers will choose to participate, given strong commodity prices, isn’t clear yet. “We have severe concerns,” Salazar says, “but this allows us an opportunity to turn this thing around.”

Salazar and others also believe that the valley can shrink its agricultural economy and survive, in part by transitioning land to other uses, such as the huge solar power developments that are now underway. The valley already is home to three large-scale solar projects, and another is in the planning stages. According to the San Luis Valley Development Resources Group, an organization working to oversee economic development in the valley’s 18 communities, the latest solar project, SolarReserve, would replace a 6,200-acre farm that consumed about 6,300 acre feet of water per year with an energy project that will consume about 150 acre feet of water per year. The project will also provide 250 to 600 construction jobs over a 30-month period and create 50 permanent jobs when it is complete.

Michael Wisdom, executive director of the San Luis Valley Development Resources Group, is working with the state to understand exactly how much damage to local incomes and the tax base will occur as the farm economy changes. Roughly 21 percent of the 22,118 jobs in the valley, nearly 4,650, are directly tied to agriculture, according to the resources group.

Wisdom is optimistic the rising demand for food worldwide will help boost commodity prices and that the valley will prevail in protecting the lion’s share of its farms. “Some are worried about smaller water; some are worried about the next steps they’re going to take to stay on the farm,” Wisdom says. “I believe the focus and culture of agriculture will still be here in 20 years.”

Many are also hopeful that a new drip irrigation pilot program, funded in part by the state’s Water Supply Reserve Account and the valley’s potato growers, could reduce the amount of water needed to grow high value crops by as much as 25 to 30 percent. “They do this all over the world,” Ehrlich says. “We just have to see if it is economical here.”

In the meantime, back out on the flats of the valley, farmers are girding for another dry year. Doug Messick was born in the valley on a potato farm near Center, and he now manages a significant operation for another company. Messick is one of the farmers who went door-to-door back in 2006, talking to friends and neighbors about the need to create the first subdistrict and gathering the signatures required for the courts to approve the plan. Six years later, though, the aquifers are still struggling, and as Messick drives his fields in the morning, he sees clearly which growers still have access to water and which do not. “A lot of the people out here are only farming half their ground now,” he says. And more and more fields in the valley have taken on a look of desolation.

“It just doesn’t look as prosperous as it once did. Over there,” Messick says, gesturing toward one set of well-tended fields, “it’s the Holy Land…those folks still have access to groundwater and they have good surface supplies, but over there,” he says, gesturing toward abandoned fields covered in scrub growth known as chico, “It’s the Little Sahara.”

Print

Print