Fourteen people gathered around a table in a Denver conference room deep within the confines of the Colorado Parks and Wildlife complex and showed one another chart, after chart, after chart.

Lines depicting vanishing snowpack fell farther and farther toward zero on their graphs and deep red stains on maps outlining the boundaries of this year’s dry season grew brighter and larger.

It was mid-June and those members of Colorado’s Water Availability Task Force (WATF) gathered in Denver could see what was becoming clearer each week. That 2018 was shaping up to mirror three other alarming drought years this century that nearly brought Colorado to its knees: 2002, 2012 and 2013. The task force, a group of water managers, scientists and hydrologists, is charged with monitoring water supplies for farms, cities and industry statewide.

Peter Goble, a staffer with Colorado State University’s Colorado Climate Center and a member of the WATF, had been anxiously watching precipitation levels for weeks. May, he reported, was the second driest May on record, based on measurements dating back to 1895. The absolute driest May occurred in 1934, the fourth year of the Dust Bowl.

“It’s pretty startling,” said Taryn Finnessey, senior climate change specialist with the Colorado Water Conservation Board and chair of the WATF.

Summer temps soar

Though reservoirs are fairly full this year, demand is rising quickly in dry spots such as the Arkansas and Southwest Basins. And even on the Front Range, where snowpack was close to normal, weeks of searing 90-plus degree days have sprinklers running at full force and reservoir levels dropping quickly.

Dixie Luke holds hay at her farm near Hotchkiss. Luke said that last year on July 4 they paid $120 a ton for hay. “If you can buy hay now, it’s every bit of $250” a ton, she said. Credit: Chancey Bush, Grand Junction Sentinel

In May, after a recommendation by Finnessey and the task force, Colorado Gov. John Hickenlooper activated the state’s drought response plan for 34 southern counties, making them eligible for millions of dollars in federal drought relief, among other forms of assistance.

Within weeks, wildfires began chasing one another across the state, spreading at rates never seen in the dry southwestern counties. The Spring Creek fire is on track to becoming one of the largest ever in the state, while the 416 fire outside Durango temporarily shut down some of the state’s most treasured tourist spots, including the scenic Durango and Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad.

But unlike the earlier drought years of this century, 2018 is no longer viewed as a standalone event. It’s been given a much chewier title. Scientists and water managers call it an entry into a multi-decadal drought period, and some worry it may signal a transformation of Colorado’s climate. Where this was once considered a semi-arid region, this 18-year dry spell may signal a dramatic change in the landscape—one in which Colorado becomes known largely as an arid, rather than semi-arid region.

Aridification is the term Brad Udall likes to use to describe what’s been going on since 2000, if not earlier. Udall is a scientist with Colorado State University’s Colorado Water Institute and a member of the multi-state Colorado River Research Group, based at the University of Colorado at Boulder.

Finding the right word

“Using old terminology, we could call it a drought,” Udall said. But he believes the term aridification is more accurate because of the ongoing reductions in snowpacks and subsequent river flows that have been seen this century.

Credit: Steve Miller

Here’s what Udall and others find worrisome:

- The Colorado River, whose headwaters lie in the Never Summer Mountains in Rocky Mountain National Park, has seen a 20 percent reduction in flows since 2000, the date many use to describe the beginning of this multi-decadal drought period, according to the Colorado River Research Group.

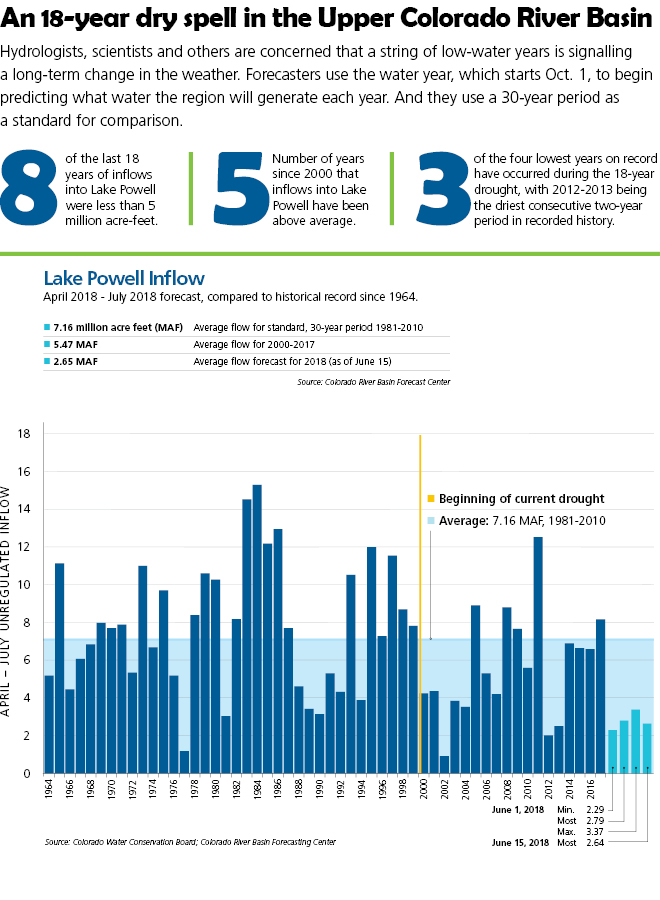

- In the same period, only five years have delivered above average flows into Lake Powell, which along with Lake Mead, serves as one of the two largest reservoirs on the river.

- Three of the four driest years on record in the Colorado River Basin have occurred during this 18-year period, with 2012 and 2013 being the driest consecutive years since 1906, according to the Colorado Water Conservation Board.

- Colorado, Utah, Wyoming and New Mexico are responsible for delivering roughly 8.23 million acre-feet (MAF) of water to the lower basin states each year by releasing it from Lake Powell. But since 2000, inflows into Lake Powell, where those deliveries are stored, have averaged just 5.74 MAF annually, meaning trying to keep up with the required deliveries is now a losing game.

Shrinking river flows

Adding to those concerns is this river-busting year of 2018, when just 2.64 MAF is expected to flow into Powell, 37 percent of average, according to data from the Colorado River Basin Forecast Center in Salt Lake City.

“2018 will not be remembered as a good water supply year for the Colorado River Basin,” Finnessey said.

Why should Coloradans care so much about the Colorado River? Because it keeps huge tourist, fishing and farm economies on the West Slope alive, it delivers roughly half the water used on Colorado’s Front Range, and it serves millions of people in Arizona, Nevada and California.

If the hydrology is changing permanently, it means most of the state’s water users will be forced to use less, and in some years, if Colorado can’t deliver enough to Arizona, Nevada and California, as the law requires, they might have to do with a lot less.

The grim scenario isn’t lost on Jesse Kruthaupt. He and his family operate a small 500-acre ranch outside Gunnison. For decades its luscious hay meadows have flourished along the banks of Tomichi Creek. Typically the creek will go dry late in the summer. “But right now,” he said, in late June “our diversion is totally dry.”

Kruthaupt will see his hay production drop this year but at least he will have a crop and enough to feed his cows and calves. “I know we will be short,” he said. “I just don’t know by how much.”

On the urban Front Range, 2018 has been a year to count blessings. In Highlands Ranch, Water Resources Administrator Swithin Dick watched his district’s reservoirs fill nicely, because in the South Platte Basin, which serves metro Denver and much of the urban north, snowpack came in at nearly normal levels.

“The South Platte Basin is the place to be this year,” Dick said. Still, the district has permanent conservation measures in place that prohibit its 96,000 residents from watering between 10 a.m. and 6 p.m., among other things.

“Our snowpack was diminished, but it’s not dire like it is for southern Colorado and southwestern Colorado,” he said.

Looking ahead, if 2019 delivers the same brand of dry as this year did, it will be much harder to tolerate because reservoirs from Durango to Denver will be depleted and will struggle to refill.

Front Range communities that lucked out this year, may not next year.

Thirsty urban customers

Denver Water, the largest municipal water utility in the state, has seen conditions deteriorate since April. It thought then that its reservoirs would fill completely, thanks to late spring snows.

But that didn’t occur, and Greg Fisher, Denver Waters manager of demand planning, said the super hot temps this summer have everyone at the agency keeping a close watch on the weather and how much water customers are using.

“We find ourselves in extremely hot, dry conditions and our use is up for sure,” Fisher said.

To date there hasn’t been a huge spike in demand and as a result the agency does not intend to impose water restrictions.

“We got very, very lucky this year,” Fisher said. “But the fact that our system didn’t fill is concerning. That often marks the start of a drought cycle for us.”

Despite the growing frequency of dry years, Udall sees some cause for optimism. “We’ve learned a lot in the last 15 years in terms of how to work with each other and how to come up with solutions that benefit everybody. Colorado has more going on in water in a good way than anywhere else in the West,” he said.

The state has, for instance, created nine regional roundtables representing its river basins and the metro area. These groups operate to address their own water issues, while working with other basins with whom they share supplies.

Those collaborative efforts are evident every month at the Water Availability Task Force meetings, where Eastern Plains ranchers weigh in with West Slope water managers and others representing Denver Water, Colorado Springs Utilities and Aurora Water, among others.

Still this year the work has been grueling. When one scientist asked if the group wanted to look at one more water supply index last month, John Stulp, Gov. Hickenlooper’s water policy adviser, smiled and said no, not really.

“I think we’re depressed enough,” he said. And he was only half joking.

Jerd Smith is editor of Fresh Water News. She can be reached at 720-398-6474, on twitter at @jerd_smith and at jerd@yourwatercolorado.org.

Fresh Water News is an initiative of Water Education Colorado. Our editorial policy can be viewed here.

Print

Print