The 96-degree heat has barely broken early on a September evening near Fruita, Colo. As the sun prepares to set, the ailing Colorado River moves thick and quiet next to Interstate 70, crawling across the Utah state line as it prepares to deliver billions of gallons of water to Lake Powell, 320 miles south.

This summer the river has been badly depleted—again—by a drought year whose spring runoff was so meager it left water managers here in Western Colorado stunned. As a result Lake Powell is just one-third full and its hydropower plants could cease operating as soon as July of 2022, according to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.

“We’re looking at a very serious situation from Denver all the way to California and the Sea of Cortez,” said Ken Neubecker, an environmental consultant who has been working on the river’s issues for some 30 years. “I’ve never seen it in a worse state.”

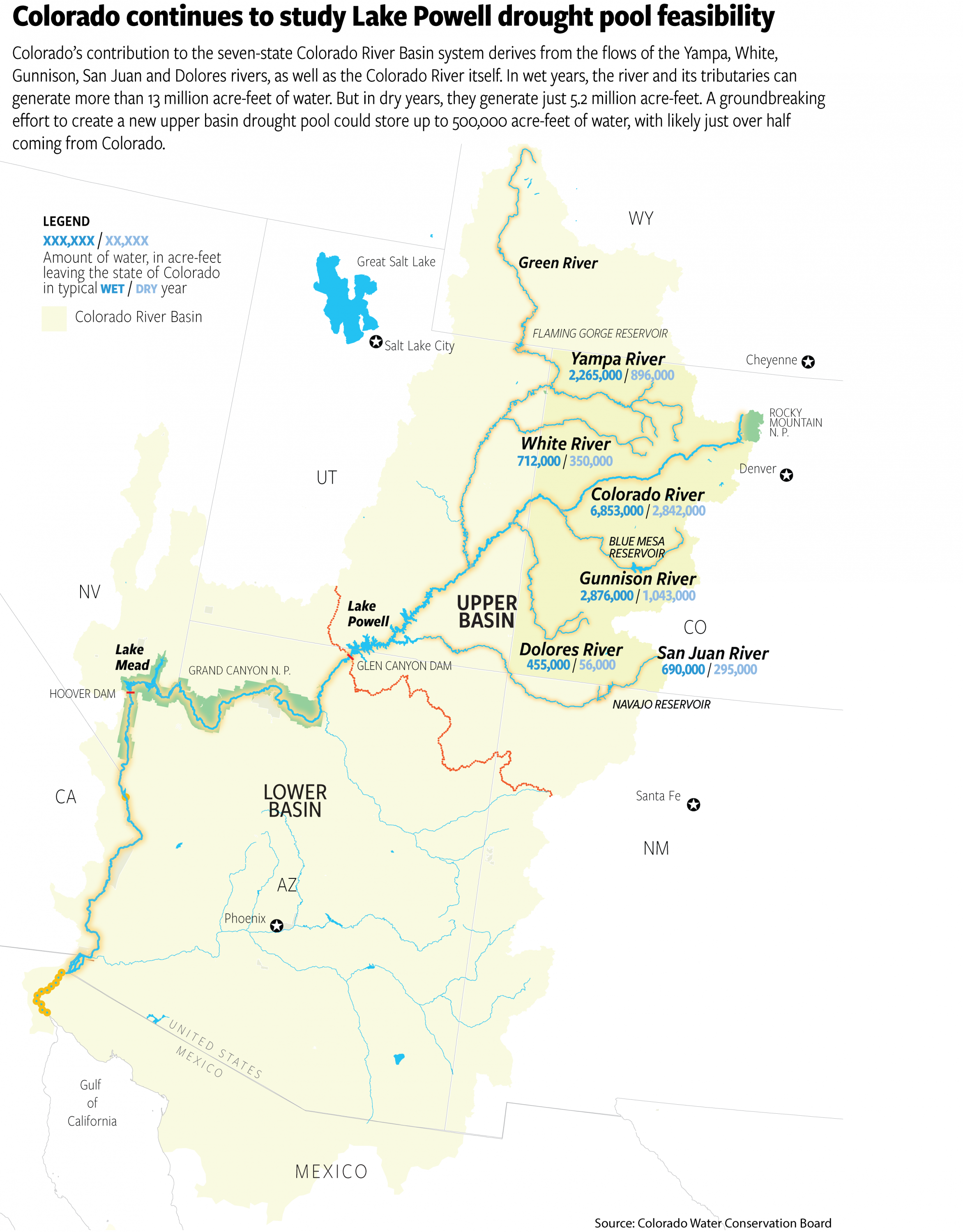

The Colorado River Basin is made up of seven states. Colorado, Wyoming, Utah and New Mexico comprise the upper basin and are responsible for keeping Lake Powell full.

Arizona, California and Nevada comprise the lower basin and rely on Powell’s larger, downstream sister reservoir, Lake Mead, just outside Las Vegas, to store water for delivery to Las Vegas, Phoenix, Los Angeles and more than 1 million acres of farmland.

These are two of the largest reservoirs in the United States. Few believed Mead, built in the 1930s, and Powell, built in the 1960s when the American West had just begun a 50-year growth spurt, would face a future where they were in seeming freefall. The two reservoirs were last full in 2000. Two years ago they dropped to 50% of capacity. Now they are operating at just over one-third their original 51 million-acre-foot combined capacity.

First-ever drought accord

Two years ago, this unprecedented megadrought prompted all seven states to agree, for the first time, to a dual drought contingency plan—one for the upper basin and one for the lower. In the lower basin, a specific set of water cutbacks, all tied to reservoir levels in Mead, were put in place. As levels falls, water cutbacks rise.

Those cutbacks began this year in Arizona.

But in the upper basin, though the states agreed to their own drought contingency plan, they still haven’t agreed on the biggest, most controversial of the plan’s elements: setting aside up to 500,000 acre-feet of water in a special, protected drought pool in Lake Powell. Under the terms of the agreement, the water would not have to be released to lower basin states under existing rules for balancing the contents of Powell and Mead, but would remain in Powell, helping to keep hydropower operations going and protecting the upper basin from losing access to river water if they fail to meet their obligations to Arizona, Nevada and California.

Rancher Bryan Bernal irrigates a field that depends on Colorado River water near Loma, Colo. Credit: William Woody

The pool was considered a political breakthrough when it was approved, something to which the lower basin states had never previously agreed.

“It was a complete reversal by the lower basin,” said Melinda Kassen, a retired water attorney who formerly monitored Colorado River issues for the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership.

But the idea was controversial among some powerful upper basin agricultural interests. Ranchers, who use some 80% of the river’s water, feared they would lose too much control of their own water supplies.

Seeking volunteers

As proposed, the drought pool would be filled voluntarily, largely by farmers and ranchers, who would be paid to temporarily dry up their hay meadows and corn fields, allowing the saved water to flow down to Powell.

Two years ago, when the drought contingency plan was approved, the four upper basin states thought they would have several years to create the new pool if they chose to.

But Powell’s plunging water levels have dramatically shortened timelines. With a price tag likely in the hundreds of millions of dollars, confusion over whether saved farm water can be safely conveyed to Powell without being picked up by other users, and concerns over whether there is enough time to get it done, major water players are questioning whether the pool is a good idea.

“It was probably a good idea at the time and it’s still worth studying,” said Jim Lochhead, CEO of Denver Water, the largest water utility in Colorado. “But it can’t be implemented in the short term. We don’t have the tools, we don’t have the money to pay for it, and we don’t have the water.”

Neubecker has similar concerns. “I fear it’s going to be Band-Aid on an endlessly bleeding problem…we need to do more.”

Since 2019 the State of Colorado has spent $800,000 holding public meetings and analyzing the legal, economic and water supply issues that would come with such a major change in Colorado River management.

Still no decisions have been made.

A call to act

Becky Mitchell is director of the Colorado Water Conservation Board, which is overseeing the analysis.

Aware of frustration with the state’s progress on studying the drought pool’s feasibility, formally known as its demand management investigation, Mitchell said the work done to date will help the state better manage the river in a drier future with or without the drought pool.

“We’re still ahead of the game in terms of what we’ve done with the study. The other states are looking at feasibility investigations but ours has been incredibly robust,” Mitchell said. “If we’re going to do it we have to do it right and factor all these things in. Otherwise we’re going to be moving backward.”

One example of a step forward is that new tools to measure water saved from fallowing agricultural land are now being developed.

A large-scale experiment in a swath of high-altitude hayfields near Kremmling has demonstrated that ranchers can successfully dry their fields and deliver Colorado River water to the stream in a measurable way, and the data is considered strong enough that it could be used to quantify water contributions to the drought pool.

Ranchers Joe Bernal, left, and his son Bryan inspect a feed corn field that depends on Colorado River water near Loma, Colo. Credit: William Woody

But other regulatory and physical barriers remain.

Under Colorado’s water regulations, rivers are only regulated where they cross state boundaries when water is scarce and the state would otherwise be unable to meet the terms of agreements with downstream states. But this is not yet the case on the Colorado River and its tributaries, so rules for determining who would get what in the event of cutbacks haven’t been developed.

In addition, because there has never been a so-called “call” on the Colorado River, the state has yet to require that all those who have diversion structures pulling from the Colorado River system measure their water use.

The situation is changing fast, though, with the 20-year drought and the storage crisis at Powell and Mead increasing pressure on state regulators to take action.

Now the state is taking steps to better monitor the river and its tributaries, moving to require that all diversion structures have measuring devices so it has the data it needs to enforce its legal obligations to the lower basin. If, for instance, some water users had to be cut off to meet the terms of the 1922 Colorado River Compact, the state could manage those cutbacks based on the water right decrees users hold that specify amount and priority date of use.

Such data would also be needed to administer a mass-fallowing program to help fill the Lake Powell drought pool.

Kevin Rein, Colorado’s State Engineer and top water regulator, said what’s known as the mainstem of the Colorado River is fairly well monitored but major tributaries, such as the Yampa and Gunnison, are not.

“A lot of tributaries don’t have the devices,” Rein said, adding that the state doesn’t know the extent of the problem. “But in important areas a lot of commissioners know there is a significant lack of measurement devices and that makes water administration difficult.”

Joe Bernal is a West Slope rancher whose family has been farming near Fruita since 1920. He has water rights that date back to 1898 and, like others in this rich agricultural region, he and his family have abundant water.

Bernal was an early supporter of the drought pool. He and his family participated in an experimental fallowing program in 2016, where they were paid to dry up their fields. He’s confident the problems can be solved.

But he’s also worried that the 500,000 acre-foot pool may not hold enough water to stabilize the river system and that it may not be done fast enough.

“We want to be sure the solution does some good, but the clock is ticking,” he said. “We don’t want to change the culture of this valley or our ability to produce food. But I think things need to move faster. We are taking too long implementing these solutions.”

Checking the averages

As Powell and Mead continue to drop—they were roughly half full just two years ago— Mitchell and Rein are quick to point out that Colorado remains in compliance with the 1922 Compact, which requires the upper basin to ensure 7.5 million acre-feet of water reaches the lower basin at Lee Ferry, Ariz., based on a 10-year rolling average. Right now the average is at roughly 9.2 million acre-feet, although it too is declining as the upper basin’s supplies continue to erode due to drought and climate change.

The Colorado River flows past fruit orchards near Palisade, Colo. Credit: William Woody

Climate scientist and researcher Brad Udall has estimated that the upper basin may not be able to deliver the base 7.5 million acre-feet in a year as soon as 2025. But the upper basin would remain in compliance with the 1922 Compact even then because the rolling average remains healthy.

Still, if the reservoirs continue to plummet as quickly as they have in the past two years, when they dropped from 50% to 30% full, the upper basin could face a compact crisis faster than anyone ever anticipated.

Major water users in the state, such as Denver Water, Northern Water and Pueblo Water, have water rights that post-date, or are junior to, the 1922 water compact, meaning their water supplies are at risk of being slashed to help meet lower basin demands.

The big dry out

Many river advocates hope the drought pool is approved because they believe it is an opportunity to test how the river and its reservoirs will work as the region continues to dry out.

“What we knew in 2018 [when the drought pool was conceived] is that we have more to do,” said Kassen. The drought pool, she said, “was a big win and offers a way of testing what the upper basin can do. It’s squandered if they don’t use it.”

Neubecker and others say it’s becoming increasingly clear that the river’s management needs to be re-aligned with the reality of this new era of climate change and multi-year drought cycles.

And that means that water users in the lower basin and upper basin will need to learn to live with how much water the river can produce, rather than how much a century-old water decree says they’re legally entitled too.

“We’re facing a 21st Century situation that was totally unforeseen by anyone,” Neubecker said, “and we no longer have the luxury of time.”

Jerd Smith is editor of Fresh Water News. She can be reached at 720-398-6474, via email at jerd@wateredco.org or @jerd_smith.

Fresh Water News is an independent, nonpartisan news initiative of Water Education Colorado. WEco is funded by multiple donors. Our editorial policy and donor list can be viewed at wateredco.org.

Print

Print