At the end of last summer, Blue Mesa Reservoir in western Colorado was at 30 percent full, its lowest elevation since 1984. A dry winter and spring forced communities and farmers to rely on reservoir storage more than ever before. For Travis Daves, a farmer in the Dolores River Basin in southwestern Colorado, some of his alfalfa crops just went dry.

“It hurt some of these stands real bad,” he said. “Some of these hay fields were just so short of water.”

But in just one year’s time, the state’s water storage system has seen a complete turnaround, thanks to the heaps of snowpack left behind by the record-breaking wet winter. According to groups that monitor water, the extremity of the year’s water flip flop can’t be overstated; the state went from having one of the bottom five worst water years on record to one of the top five.

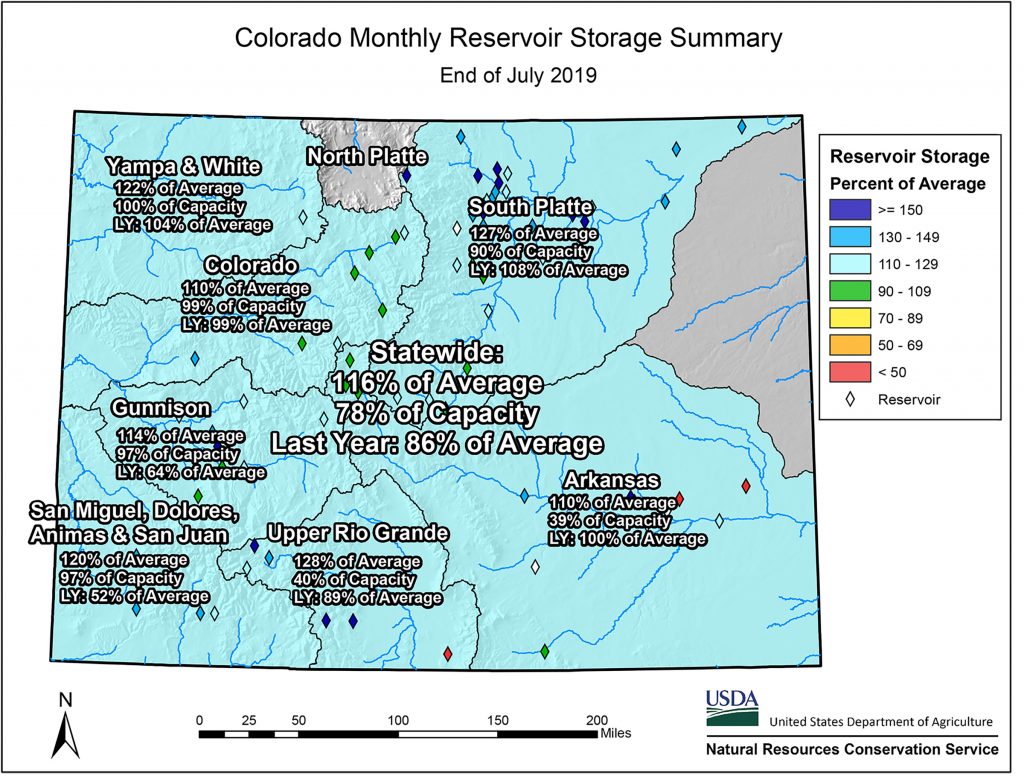

“Every single major basin in the state has above-average storage,” said Karl Wetlaufer, a snow survey hydrologist with the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) in Colorado. “It’s the first time in a long time that’s happened, especially compared to where we were last year.”

Many of the biggest swings in reservoir storage were in areas that were the worst off last year. Blue Mesa reservoir is now 95 percent full. The Gunnison Basin, where Blue Mesa gathers its water, and the combined San Juan, Dolores and San Miguel basins also saw upward shifts in average reservoir storage of more than 50 percentage points from this time last year.

Even after a summer of irrigating and lawn watering, combined storage statewide stood at 116 percent of average as of July 31, the latest figures available from the NRCS. Last year during the same period, statewide storage stood at just 86 percent of average.

The hefty mountain snowpack fed not only Colorado’s dwindling reservoirs, but other water storage facilities throughout the entire region. Lake Powell, the largest reservoir in the Western United States, fell to 35 percent full last year, one of its lowest elevations of all time. As of September 2 this year, it was 55.9 percent full.

“This time last year we were in the middle of the third driest year in the recorded record,” said Marlon Duke, a spokesperson for the Upper Colorado Basin with the Bureau of Reclamation. “In the early runoff months [this year] we had so much water flowing into Lake Powell that the reservoir was rising as much as a foot a day. Campers in the area had to be careful where they put their tents to keep them out of the water.”

But while reservoirs have been able to refill, water experts in Colorado and the rest of the region warn that one year of good snowpack isn’t enough to alleviate concerns about water shortages.

“The previous snowpack year and subsequent boon to the reservoir supply is of course great news, but it doesn’t have any significant bearing on what we can expect going forward,” said Peter Goble, a climatologist with the Colorado Climate Center. “We did better than a normal year in 2019, but there is still a lot of empty storage to fill up, and that’s more of a long-term problem.”

According to Goble, predictions of a wetter-than-normal end of summer have failed to materialize in Colorado, and it’s hard to say what winter may bring. In the face of this uncertainty, water managers have emphasized the importance of the Drought Contingency Plans that Congress authorized this year in both the upper and lower basins of the Colorado River.

These plans require states in the lower basin to take water cuts under certain hydrological conditions, and lay out a framework for the upper basin to explore large-scale conservation efforts to preserve elevations at Lake Powell.

“What this year did is that it gave us just a little bit of breathing room, but there is still work to do in this [the upper] basin and that is what makes the Drought Contingency Plan so important,” Duke said.

While the wet winter helped to alleviate the extreme drought conditions experienced throughout the West last year, the region still hasn’t entirely recovered from 2017 and 2018. Many of the large reservoirs throughout the Colorado River Basin, like Lake Powell and Lake Mead, remain at chronically low elevations.

Aug. 15 the Bureau of Reclamation released its 24-month study modeling future elevations for Lake Mead and Lake Powell. The study showed Lake Mead just below the threshold to trigger water cuts for next year in Arizona and Nevada, as well as in Mexico, as part of the Lower Basin Drought Contingency Plan.

Last year’s dry conditions can also still be felt on the ground. According to Travis Daves back in the Dolores Basin, some of the hay fields still haven’t recovered from the lack of water last year. He thinks some of his crops may never recover.

“It does something to the plants,” he said. “They are starting to look better but it’s amazing that even after the good winter we had we couldn’t keep up.”

Lindsay Fendt is a freelance journalist based in Denver. She covers water and the environment in the West and abroad. She can be reached at lindsayfendt@gmail.com.

Fresh Water News is an independent, non-partisan news initiative of Water Education Colorado. WEco is funded by multiple donors. Our editorial policy and donor list can be viewed at wateredco.org

Print

Print