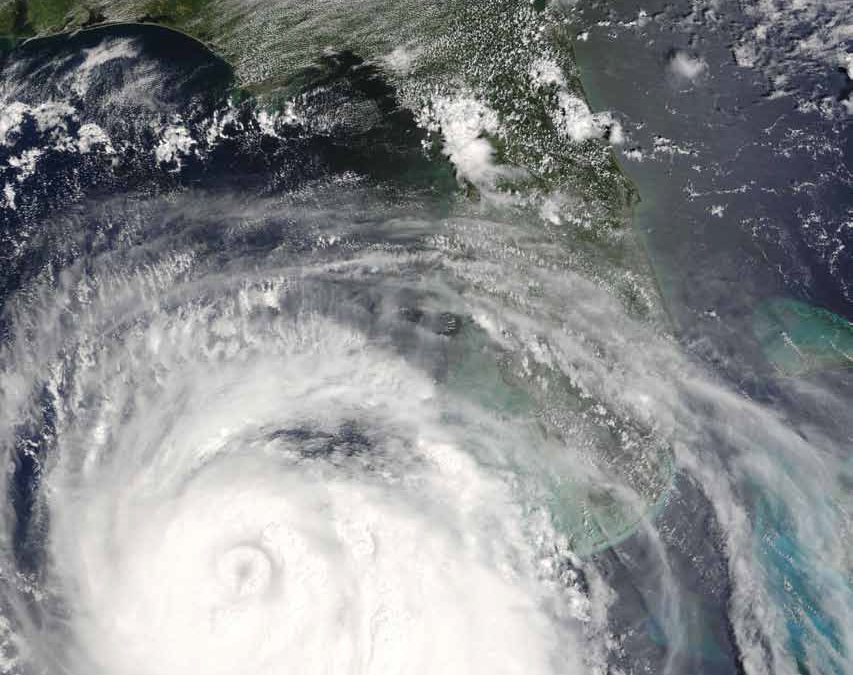

On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina stormed into the Gulf of Mexico, ravaging coastal communities with gale-force winds and sheets of rain.

The tempest would prove to be the second deadliest hurricane in American history. More than 1,800 people died, and thousands more were displaced or left stranded for days amidst threatening floods. Much of the destruction occurred in New Orleans, where floods breached the city’s levees and the system failed catastrophically. All told, the hurricane caused an estimated $81 billion in damages.

Nearly as tragic was the fact that much of the destruction might have been prevented. Immediately after the hurricane, experts pointed to the loss of roughly one million acres of coastal wetlands as the major chink in the regional armor. Rather than absorbing rain and wind, buffering the wrath of the storm and protecting nearby land and communities, what remained of the wetlands was battered into smithereens. Had the wetlands’ flood protection value been calculated long before a web of canals were built through them to accommodate the oil and shipping industries and flood control measures cut them off from the Mississippi River’s natural sedimentation, it is possible that the land would have been more valuable in its natural state than as commercial and industrial real estate.

Unfortunately, it took the dramatic consequences of the hurricane to make that apparent. In ecological jargon, the protection those wetlands originally provided is known as an ecosystem service, a valuable role played by nature that offers extraordinary benefits to humans. Clean air. Medicinal plants. Recreational opportunities. Flood protection. Water filtration. Nutrient cycling.

These services are so ubiquitous, such an inherent part of the world we inhabit, that for decades they were all but completely taken for granted. Development, extraction of oil, gas, and metals, burning of fossil fuels, and scores of other human actions have degraded ecosystems, setting the stage for very expensive treatment processes or highlighting the critical need for environmental restoration. In the words of Joni Mitchell, often you “don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone.” Now that many of these services have been compromised and the consequences felt, a growing trend is taking root to recognize, value and protect ecosystems before their natural functions are lost.

Identifying ecosystem services and forming restoration efforts around them—essentially making anthropogenic arguments in favor of conservation—may seem mercenary compared to save the whales campaigns of yesteryear, but in actuality, such efforts offer a pragmatic perspective that creates more buy-in from a variety of stakeholders. Unlikely partnerships are sprouting between for-profit industries, many of which for years have been suspect to the environmental community, and the environmentalist. For instance, The Nature Conservancy is working with Bavaria, the largest brewery in Colombia, to help preserve the watershed that serves Bogotá, the country’s capital.

With its headwaters located in Chingaza National Park, Bogotá’s water supply emerges at its source clean and pure. But as it travels to the thirsty city, population roughly 7 million, the Chingaza River and its tributaries face an assault from logging, farming and other human activities that clog the waterways with sediment, metals and nutrients. The water arrives so polluted that the costs of treating it for drinking water have skyrocketed. Those costs are ultimately passed on to water users, one of the biggest being Bavaria Brewery. This results in a noticeable reduction of the brewery’s profits.

The Nature Conservancy demonstrated that by contributing to a watershed conservation fund that would invest proactively in watershed protection, Bogotá’s water utility could save $4.5 million annually. Water users would ultimately benefit from supporting land use practices that could reduce sedimentation in the water by 2 million tons a year. Businesses would recoup their investment in four to five years, according to the Conservancy. The pitch worked. Bavaria Brewery joined the cause along with other private companies.

Presenting conservation as an investment—and not just an altruistic act—is giving rise to public and private partnerships aiming to provide funding to maintain or restore ecosystem services, such as those rendered by an intact watershed. According to the March 2010 issue of Wired magazine, some of these creative arrangements are helping not only to put water back in rivers, but to improve water quality. For instance, new regulations in the Pacific Northwest allow industrial operatives such as paper mills, whose activities can raise water temperatures, to “offset their actions by investing in nature’s ability to cool the water. Instead of spending tens of millions of dollars to build cooling towers, companies might contract with local conservation groups to restore stream-side vegetation that naturally lowers the water temperature and shores up habitat for cool-water fish.”

Employing Ecosystems to Protect Water Quality

In Colorado, protecting ecosystems for their ability to filter and sequester nutrients is likely to become a high priority once the state adopts criteria regulating nutrient levels in open water bodies and streams. As mandated by the Environmental Protection Agency, Colorado’s Water Quality Control Commission will set criteria for phosphorous and nitrogen in 2012.

Prof. Jim Loftis, of Colorado State University, along the Cache la Poudre river in Fort Collins. Loftis studies nutrient loading in watersheds resulting from agriculture and water treatment facilities. Photo By: Kevin Moloney

Excessive nutrients can lead to prolific algal blooms that choke the oxygen from water and render aquatic environments nearly sterile and hostile to fish. Algal blooms not only threaten the ecological integrity of water bodies, they necessitate extensive—and expensive—drinking water treatment, says Dr. Jim Loftis, professor of civil and environmental engineering at Colorado State University. Water with significant organic matter requires more intense treatment to disinfect. Some of the byproducts of the disinfection process are known carcinogens and are regulated by the EPA, so treatment plants will need to invest more money to comply with the criteria that govern their release. “Nutrients are probably the main headache of water treatment managers,” says Loftis.

Perhaps surprisingly, inflated levels of nitrogen and phosphorous don’t stem just from human-applied fertilizers and detergents, though that is one source. These naturally-occurring nutrients are “everywhere,” says Loftis. “Anyplace there is soil, there are nitrogen and phosphorous, and if you fertilize the soil to grow crops, there’s more. They are released from wastewater treatment plants. Anywhere there is human activity there is an increase in nutrients.”

Because these nutrients are found in soils, human disturbances, such as mining or deforestation, also play a role by inducing soil erosion. Soil eroding from a road cut, for example, carries nutrients with it into rivers and streams.

While eliminating nutrients altogether would be impossible, not to mention undesirable—they are an essential input to natural systems—reducing their unnatural prevalence in water bodies can be accomplished in a number of ways. Upgrading wastewater treatment plants, preventing agricultural runoff, and keeping urban runoff or polluted storm water from reaching streams and rivers are all possible methods of reducing nutrient pollution. Another solution is to use wetlands as buffers to absorb and retain nutrients.

In Bear Creek Lake, outside of Morrison, recent restoration efforts focused on stabilizing the reservoir’s banks and preventing them from eroding, which has led to a measurable reduction in nutrients in the lake, says Russell Clayshulte, a water consultant working on the project on behalf of the city of Lakewood. Along with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, in 2007, the city spearheaded the restoration of a section of the reservoir that was an eighth of a mile long. After installing five stabilization structures, building wetlands and planting trees, they measured nutrients in the water and compared them to pre-restoration levels. Before, the eroding sediments were bringing an average of 20 pounds of phosphorus and 200 pounds of nitrogen into the reservoir each month. The year after construction, those numbers dropped to 4 pounds of phosphorus and 125 pounds of nitrogen per month. Over the past two years, Clayshulte says the amount of nutrients has increased, likely as a result of housing development upstream of the reservoir and more storm events. Nevertheless, he says the restoration provided measurable benefits and added that the new wetland is likely absorbing much of the increased nutrients from the development.

Even though the cost of wetland restoration can range from several thousand to millions of dollars, upgrading the state’s wastewater treatment plants to meet the yet-unspecified nutrient criteria could be prohibitive to small plants serving rural customers, says Nancy Keller, regulation compliance specialist for the city of Pueblo. Estimates for the financial impact to Colorado from the nutrient criteria standards are hard to come by because the rule-making process isn’t complete. But Keller points to a similar criteria-setting process in Florida that required some wastewater treatment plants to pay up to $5 billion in upgrades to meet the new regulations.

“If the standards here are similar, many wastewater facilities will have to go to reverse osmosis treatment, which consumes huge amounts of electricity, releases significantly more greenhouse gases and will have a toxic brine that will need to be disposed of,” says Keller. “It will be tremendously expensive.” Those costs will most likely be passed on to customers in the form of higher sewer and water rates.

Given the projected expense, finding opportunities in nature that will keep nutrients from pouring into the waterways is an attractive option that is likely to play a large role once municipalities and treatment plants take action to conform to the new regulations, says water consultant Rob Buirgy.

With 80 percent of the earth’s atmosphere consisting of nitrogen, and with the prevalence of nitrogen-fixing life forms that easily convert that into usable nitrogen, controlling nitrogen through ecosystem services restoration is challenging. However, phosphorus, which is found in soils and decomposed plant matter as well as animal waste and artificial fertilizers, is easier to manage, Buirgy says. Most nutrient-related pollution problems in Colorado are phosphorus-dependent, so controlling phosphorus will likely have a direct beneficial effect.

“A healthy natural system does a great job of sequestering phosphorus in soil and living organisms,” says Buirgy. “Any free phosphorus will most likely be taken up by growing plants and incorporated into the natural cycle.” In other words, a functioning, healthy wetland will trap phosphorus while concrete ditches, along with roads, driveways and houses, will let the nutrients flow over them and into the water supply.

“You’ll see phosphorus moving through a developed landscape in far greater amounts than through a ‘natural’ landscape,” says Buirgy. “Consequently, in almost every case, a functioning ecosystem will go a long way toward addressing the nutrient issue.”

Salvaging a Water Source

One Front Range water body that stands to benefit from the nutrient criteria is Standley Lake, which provides water year-round to the cities of Westminster, Thornton and Northglenn and is a popular recreational destination. Standley Lake’s storied water quality history dates back to the early 1960s when severe taste and odor problems led to public protests. In the years that followed, the taste and smell problems were linked in part to high levels of nitrogen and phosphorus that were feeding extensive algal blooms in the lake. The algae also contributed to low levels of dissolved oxygen, to the detriment of local fish species. There were many nutrient sources: wastewater effluent discharged upstream by Coors Brewing Company, unlined 100-year-old canals that were leaching nutrients into the water supply, and storm water runoff from upstream roads and mines. An extensive clean-up effort ensued.

Water consultant Russell Clayshulte (right) and Tony Langowski of the Evergreen Metropolitan District sample a small tributary on Bear Creek for E-coli contamination. Clayshulte helped secure funding with the city of Lakewood to restore a tributary to Bear Creek Lake, a reservoir along C-470. Photo By: Kevin Moloney

In the 50 years since the original problems surfaced, the three cities, along with partners throughout the Clear Creek Watershed, which envelops Standley Lake, have taken drastic and effective steps to reduce nutrient levels in the lake. In addition to technological solutions—rerouting the Coors discharge and adding treatments to remove phosphorus from the upstream wastewater treatment plants’ effluent—cities and groups like the Upper Clear Creek Watershed Association have remediated mining sites and built wetlands to reduce the amount of storm water and pollutants running directly into the water system. Their efforts have paid off.

“Nutrient loading in Standley Lake was a very significant problem,” says Mary Fabisiak, the city of Westminster’s water quality administrator. “It isn’t a problem now, but we need to maintain this status quo. We do not want the water quality to deteriorate.”

For Standley Lake, a nutrient-loading relapse would herald a return of the water quality issues of years past and could force Westminster, Thornton and Northglenn to abandon it as a water supply. That would be astronomically expensive—Westminster has estimated that replacing its water system alone would cost $480 million, according to a report published in 2010 by the three cities that rely on Standley Lake for drinking water.

Although Standley Lake’s current, site-specific standards are likely more restrictive than what the state will ultimately implement, the lake gets some of its water from outside the Clear Creek Watershed, both from Denver Water’s supply and from Coal Creek. Water quality improvements in those watersheds would be passed along, as would further reductions to nutrient levels in treated wastewater.

Loftis thinks failure to implement sufficient criteria could result in “a slow degradation of water quality that would result in extremely high water treatment costs over time.” He points to California’s Lake Tahoe, which has no nutrient criteria and is essentially sterile due to low dissolved oxygen, as an indication that the slow process of decline can have dramatic impacts down the road. And, unchecked nutrient levels could have a compounding impact on rivers and aquatic life around the country.

“Any excessive nutrients that leach out of the watershed and make it to, say, the Gulf of Mexico via the Arkansas River would be bad,” says Loftis. Nutrient enrichment in estuaries often results in dead, or hypoxic, zones that are so oxygen deficient they are nearly devoid of aquatic life. In the Gulf of Mexico, at the mouth of the Mississippi River, one of the largest dead zones in the world fluctuates in size corresponding to seasonal farming practices and storm events.

At the mouth of the Mississippi River, where nutrient-laden sediments flowing into the Gulf of Mexico can be seen from space, a dead zone of oxygen-depleted water forms as small organisms called phytoplankton decay. Blooms of the phytoplankton, or algae, grow rapidly with the increase in available nutrients and are thought to be responsible for the green and light blue water colors seen in the photo above. NASA photo.

How do we Value Ecosystems?

While problems in a drinking water supply or the inability of an ecosystem to support life would trigger a reaction from most people, some services are less visible. In the absence of a direct, monetary value, people often have a harder time recognizing or appreciating the importance of some valuable ecosystem functions. Pam Kaval is an ecological economist who specializes in valuing ecosystem services. She believes most Coloradans understand the value of having a healthy fish population in a popular fly fishing stream, for example. But other services provided by a healthy stream, such as the wildlife communities supported by clean water or the water filtration facilitated by functioning wetlands, are less recognized.

“When you’re looking at the role a stream plays in a system, you get a more complete assessment when you add information about all the life that stream supports and the roles it plays,” says Kaval. “This is important for policy makers, sure, but it affects everybody.” For instance, protecting habitat to support native wildlife populations can draw tourists and recreationists, which has financial benefits to surrounding communities. Essentially, protecting ecosystem services means talking about restoration and its impacts in financial terms in order to explain the benefits to a universal audience, says Kaval.

“People want to know the bottom line, in dollars,” she says. “It is easier to talk dollars instead of saying, ‘Two feet of soil will have x level of impact and improve the nutrient levels by x percent.’ That doesn’t mean a lot to someone who doesn’t understand the science. So even though there’s a value to adding soil, for example, to be able to say that adding soil improves something by $50 an acre is much more effective.”

In this world where money talks, perhaps valuing ecosystems economically will help us heed the harbingers of ecosystem disturbances like that of New Orleans and its sacrificed wetlands before those sacrifices add up to more than we bargained for.

Print

Print