Bob Sakata was 20 years old when he began farming 40 humble acres on the outskirts of Brighton. Sixty-six years later, Sakata Farms covers 3,000 acres and is one of the 100 largest vegetable producers in the country. Sakata still works his fields of broccoli, sweet corn and onions with his son, Robert, and other family members. Despite his success, he has never forgotten his younger days growing up on a truck-garden farm in California and his father’s constant worries over water.

“When I came here, I saw the abundance of water from the Rocky Mountains and some wells being drilled,” Sakata recalls, “and I thought it was the ideal place to start growing vegetables.”

Many other farmers have also seized the opportunity, joining Sakata in the surrounding area of the South Platte River Basin, which begins in the Rocky Mountains and fans outward to envelop the city of Denver and the expansive plains to the east. In the postwar era, this northeastern part of the state has boomed with fields of sugar beets, corn, potatoes and barley. Snowmelt flowing from the mountains is diverted and stored to irrigate fields that otherwise would not flourish in the arid climate. The vast groundwater aquifer has also been tapped extensively through wells, additionally buffering water supplies. “That’s what made northern Colorado a real oasis in production of crops,” Sakata says.

This unlikely oasis, in fact, spreads across the state, well beyond the vegetable farms and sugar beet fields of the South Platte Basin to the fruit orchards and sweet corn fields on the other side of the Rockies, as well as the pastures and cattle of the northwest, the potato farms in the south, and the melon patches in the southeast. These working farmlands produce a bounty that feeds millions in Colorado and around the world. They also play a vital role in providing open space and wildlife habitat, which, along with agriculture itself, defines much of Colorado’s character. Through its many ups and downs, the agricultural industry has always depended on that one worrisome aspect— water.

Farms and ranches cover 32 million acres in Colorado, nearly half the state. Just under 10 percent of that land is irrigated, boosting productivity and providing a form of crop insurance. Without irrigation, farmers risk the possibility of drought induced crop failure, opening the door for substantial financial losses. But irrigation water serves as a buffer against the variability of the state’s natural rainfall.

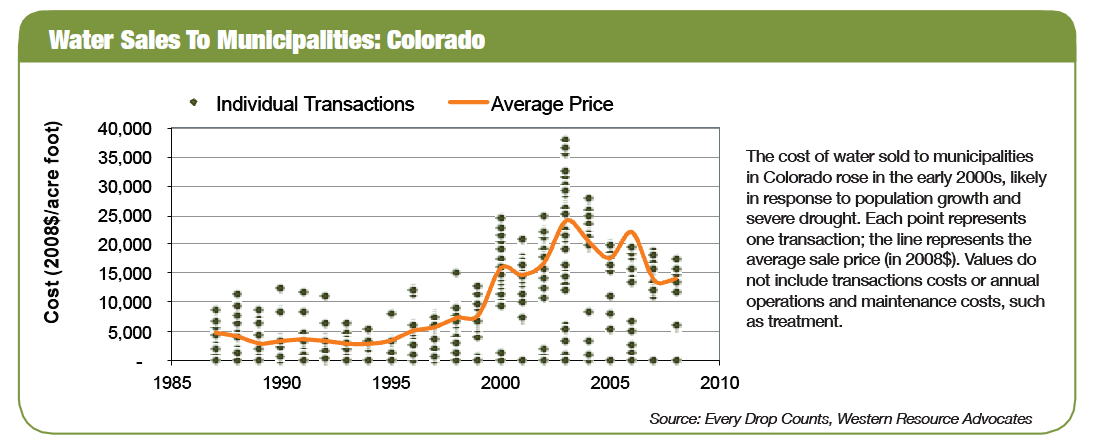

The water diverted from rivers and pumped from the ground to provide that buffer accounts for 86 percent of the state’s available water. Agriculture’s dominant share not only represents the industry’s historical importance, but also makes it an obvious target for planners and developers considering future growth. Since the 1970s, burgeoning cities in Colorado have bolstered their water supplies by buying up irrigators’ water rights and, in the process, drying up farmland. Forecasts indicate the growth trends are likely to continue and even increase, along with the demand for urban water supplies.

Even taking into account the potential for conservation and new water storage projects, many planners have presumed that the bulk of new urban water will need to come from transfers of water now owned by farmers and ranchers, says James Pritchett, an agricultural economist at Colorado State University. Without a Plan B, more than 400,000 acres—about 13 percent—of irrigated farmland in the state could dry up, with implications for farmers, consumers and the environment.

“The biggest challenge we face is making sure we understand that water needs to stay on the land to produce agricultural products,” says John Salazar, commissioner of the Colorado Department of Agriculture. “As we face enormous pressure from growth in the state, we need to start planning for the future, instead of having the future plan itself out for us.”

An Uncertain Venture

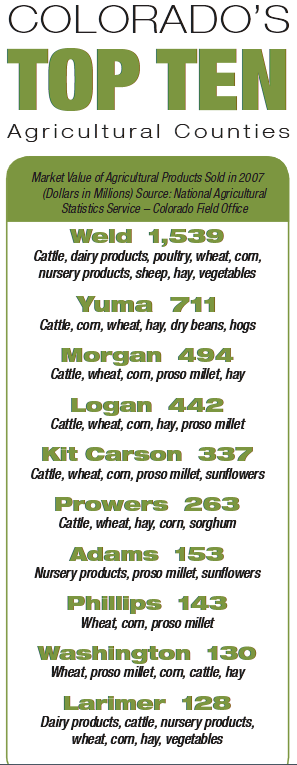

As goes farming, so goes Colorado—or at least that’s how it’s been. According to the state Department of Agriculture, farms, ranches and the food industry generate $20 billion of annual economic activity, making agriculture second only to mining and energy development in terms of its economic importance to Colorado. Agribusiness supports more than 100,000 local jobs. But despite its significant financial and geographic footprint, the idyllic mosaic of farms and food producers has always sustained itself amid hardships.

Sakata remembers the drought of 1954— which, he says, exceeded the dire conditions of the early 2000s—as the first of many trials to his operations. He turned to groundwater to supplement variable water supplies during subsequent times. But in the 2000s, new restrictions limited well pumping in much of the South Platte Basin because of suspected depletion of the underground aquifer and related legal complications. Add in capricious environmental episodes— hailstorms, pests, ravenous bird flocks—that can decimate crops, then account for the uncertainty of commodities markets, and it’s little wonder that farmers are tempted to sell their water rights to municipal suitors. “I think we’re the only business in the whole United States where there is no guarantee of what kind of price we’ll get for our product,” Sakata says. “We have such a small margin of profit [that] we have to cut everywhere we can.” In order to minimize the impacts of market whims, Sakata has diversified over the years. In addition to growing an array of vegetables, he also produces field crops, such as corn, wheat and alfalfa, that are often used for feed on beef cattle and dairy ranches.

Sakata remembers the drought of 1954— which, he says, exceeded the dire conditions of the early 2000s—as the first of many trials to his operations. He turned to groundwater to supplement variable water supplies during subsequent times. But in the 2000s, new restrictions limited well pumping in much of the South Platte Basin because of suspected depletion of the underground aquifer and related legal complications. Add in capricious environmental episodes— hailstorms, pests, ravenous bird flocks—that can decimate crops, then account for the uncertainty of commodities markets, and it’s little wonder that farmers are tempted to sell their water rights to municipal suitors. “I think we’re the only business in the whole United States where there is no guarantee of what kind of price we’ll get for our product,” Sakata says. “We have such a small margin of profit [that] we have to cut everywhere we can.” In order to minimize the impacts of market whims, Sakata has diversified over the years. In addition to growing an array of vegetables, he also produces field crops, such as corn, wheat and alfalfa, that are often used for feed on beef cattle and dairy ranches.

For its part, the beef industry is more predictable. In Colorado, roughly 70 percent of crop receipts are livestock-oriented. Many ranchers are able to subsist in tough landscapes, raising cattle in high-altitude pastures in areas such as the Yampa and North Platte river basins, along the northwestern edge of the Rockies, then trucking young herds to feedlots in the plains as the weather cools in order to “finish” the cows on a diet of corn and other feed. The demand for cattle feed, and for ethanol, has led farmers to plant a whopping 1.3 million acres of corn in Colorado, much of it in the eastern half of the state, including the South Platte and Arkansas river basins. As much as 85 percent of the corn produced goes to livestock, far above national averages, says Mark Sponsler, chief executive of Colorado Corn. He attributes this to the climate and the proximity to beef markets and processing facilities in the Midwest.

Corn acreage has held steady within the state over the past 40 years, but most growers raise corn on irrigated lands. Would it be possible to grow corn without water for irrigation? Yes, according to Pritchett, it’s possible, but productivity can drop by 80 percent. A farmer that opted to sell his water and move that direction would need to get a lot bigger, growing from say 1,000 acres to 4,000 or even 5,000, in order to continue to earn the same income. But, for farmers nearing retirement, especially in areas where the pressures from development are high, such a “conversion” may become an easier decision to make, says Pritchett.

One of the key reasons agricultural water has been targeted for purchases or transfers to municipal use is that it’s more affordable and immediately available than developing new supplies—and many farmers are assumed to be ready to sell. In the past, cities have sometimes bought out irrigators’ water rights on the down-low, purchasing water from irrigation companies as undisclosed clients. Now, utilities will seek out willing landowners who are struggling to keep their farms going and facing a cloudy future as their children look to lives outside of farming and ranching.

Some people considering the future of farming in Colorado have suggested that low-value and water-intensive crops, including corn and wheat, should be phased out in favor of more high-value crops that consume less water, such as fruit, tomatoes, garlic and hops. On some level, that’s been happening over the last few decades as niche markets in peaches, heirloom onions, sweet corn and wine grapes have flourished in the Gunnison and Colorado river basins in western Colorado and elsewhere. Such shifts might lead to agricultural water being more highly valued and could lessen the impacts of buyouts and even reduce farm water consumption. But Pritchett and Sponsler point out there’s a reason this hasn’t happened more widely. People raise crops to make farming a sustainable financial venture. Demand for high-value crops is limited, and producing too many wine grapes or heirloom onions deflates the price and undermines such efforts.

Meanwhile, the prices of crops also rise and fall depending on global food demands. Salazar notes that farming and ranching are powering Colorado through the recession, with exports increasing by 20 percent between 2010 and 2011. Prices have climbed for wheat and a few other staple crops, due in part to the migration of Chinese farmers to cities and the associated decline in agricultural production there. The result here, says Salazar, is that Colorado farmers have been planting more winter wheat.

Agricultural economists who study the trends expect corn and other livestock-supporting staples to remain prominent in state agriculture over the next 30 or so years, especially as the world consumes more beef. But there is a wild card: If consumers keep buying their food based on where it comes from and how it’s produced—and are willing to pay a premium on locally-grown, specialty products— certain high-value crops could become more significant.

The Rise of Local Markets

Bailey Stenson and her husband Dennis began Happy Heart Farm near Fort Collins 28 years ago. From the start, the Stensons have used biodynamic farming practices, a method of organic agriculture that applies compost and manures in place of chemical fertilizers and pesticides and views a farm as a unified “organism.” After their first seven years, the Stensons pioneered community-supported agriculture (CSA) in the state, selling individuals and families seasonal shares of their crop. After sustaining steady growth for more than a decade, Stenson says interest in farm shares began peaking about five years ago. Today, Happy Heart has 140 local members who pick up food shares from the farm weekly. Many other CSAs—there are now 100 operating in Colorado—deliver shares within a 25-mile or so radius.

The growth of CSAs has accompanied the expansion of farmers’ markets and grocers oriented toward natural and organic foods. Data from the USDA census shows 10 to 20 percent growth in the past decade of farm receipts of direct sales to consumers. The state’s Colorado Proud labeling program, launched in 1999, has been used to promote local products and now counts more than 1,500 farms, restaurants and retailers, including Walmart and other large supermarket chains, among its supporters.

The growth of CSAs has accompanied the expansion of farmers’ markets and grocers oriented toward natural and organic foods. Data from the USDA census shows 10 to 20 percent growth in the past decade of farm receipts of direct sales to consumers. The state’s Colorado Proud labeling program, launched in 1999, has been used to promote local products and now counts more than 1,500 farms, restaurants and retailers, including Walmart and other large supermarket chains, among its supporters.

Consumers are “waking up to the fact” that buying local and organic foods is healthy for their families and beneficial to their communities and their neighboring farmers, says Stenson. “More and more people are really wanting to connect with the people growing food.” According to a 2011 survey conducted by Colorado Proud, nearly 92 percent of Colorado residents would buy more locallygrown agricultural products if they were available and identified as such. “It’s still kind of a trendy thing,” says Stenson, “but I think with the economy and the environment right now, it’s going to go from a fun choice to an absolute necessity.”

Local food systems still need to optimize their benefits, says Dawn Thilmany, an agricultural economist at CSU who focuses on the subject. A prime example: As long as dozens of trucks from each vendor are shipping out to farmers’ markets, buying local in Colorado doesn’t necessarily reduce transportation costs. The rise of more mid-sized, food-growing operations and supply chains created for local sales and seasonal and specialty crops could reduce fragmentation in the market, Thilmany says, and deliver on assumed environmental advantages, such as saving gasoline, over conventional practices. “I think we’re seeing a shift, but I don’t know where it’s going to end,” Thilmany adds. She guesses as much as 20 percent of Colorado’s groceries could eventually come from local sources, a significant gain from present levels of 5 to 10 percent, depending on the product.

Keeping Water on the Farm

For all the goodwill and gusto toward Colorado farmers and food production, agriculture still faces the looming pressures from population growth and the likely reduction of some water use. The question is whether the pressure can be diverted or at least controlled in order to protect farming and ranching in Colorado.

For their part, many farmers and ranchers have improved irrigation efficiency on their lands, maximizing the percentage of the water they apply that actually goes to benefit the crop. According to the 2007 USDA Census of Agriculture, 49 percent of the nearly 3 million acres of irrigated farmland in Colorado now use sprinkler and drip systems that are much more efficient than traditional practices.

“You attempt to do everything you can to become efficient,” says Sakata, who has lined canals and replaced flood irrigation with pivot sprinkler systems, among other measures, over the years. “I’d like to be given credit for the fact that we’re thinking about the state and the population to conserve water, but let’s face it, it’s an economic reason too. If you waste water, you lose money.”

The catch is that efficiency improvements and water conservation have some unintended consequences, not to mention legal obstacles. By irrigating with sprinklers as opposed to flood irrigation, farmers inadvertently reduce percolation into groundwater and the eventual return of some of their irrigation water back to streams, affecting the timing and volume of river flows. The changes can harm fish and bird populations that rely on streams historically supported by these “return flows.” The altered flows can also deprive downstream users—in Kansas or New Mexico, for instance—of water they expect to receive and are legally entitled to.

Thus, in Colorado, such efficiency improvements are monitored so that downstream users are protected. If a grower needs less water for irrigating her farm due to an efficiency improvement, she doesn’t get to “keep” the savings, because technically, the crop is still consuming the same amount. Instead, the farmer must allow the unneeded river flows to continue downstream, to be available for the next user in line. And she is prohibited from transferring the rights to that water to another use, such as leasing it to a city water utility. “We need, as a state, to be working on figuring out how we can have more flexibility with how water gets used so that we can maintain the agricultural economy,” says water attorney David Robbins, “while at the same time accounting for the demands of burgeoning cities and respecting our obligations to downstream water users.”

Over the past decade, state lawmakers have attempted to create policy tools that, while still operating within state water law, could minimize the permanent sale of agricultural water rights. The Colorado Water Conservation Board has put $4.2 million toward alternatives to permanent transfers, fronting the cost for conceptual, legal and engineering work on potential solutions. Now, says Robbins, it’s up to cities and farmers to prove the concepts can work.

One promising option is a program to allow farmers to lease water rights to cities during dry years, receiving payment in exchange for letting their fields fallow. While fallow, unplanted fields could recover important soil nutrients, and at the same time give farmers a reliable income stream. But fallowing isn’t an option for fruit growers of the West Slope and vegetable farmers like Sakata, who need to protect their market share. Transporting water from rural parts of the state to populated areas also presents a logistical and financial challenge.

In the Arkansas River Basin, farmers and ranchers know the impacts of selling agricultural water rights, as many small farming towns have dwindled with past water sales. “When water goes away, people go away and the economy goes away,” says Jay Winner, general manager of the Lower Arkansas Valley Water Conservancy District.

Winner and others are trying to avoid repeating that scenario around southeastern Colorado. Through a subcommittee of the Arkansas Basin Roundtable, irrigators and water managers are teaming with CSU economists, including Pritchett, to model what the future of agriculture might look like in the region. The researchers plan to study how much land would be dried up in the basin as cities target local farmers to sell their water rights. The group will also look at which crops could expand acreages if water sharing catches on, and how technology may improve productivity in coming years.

“Our goal is: We have what we have when it comes to agriculture, and we want to keep it,” Winner says. “That entails working with the cities so that they understand the value of agriculture, not just in the Arkansas Basin, but in the state of Colorado, and to figure out a way that we can all work together for the benefits of the state to keep agriculture viable.”

Print

Print