Keeping tabs on your tap is just the first step in determining your impact on global water supplies

How much water does it take to write a story for Headwaters magazine?

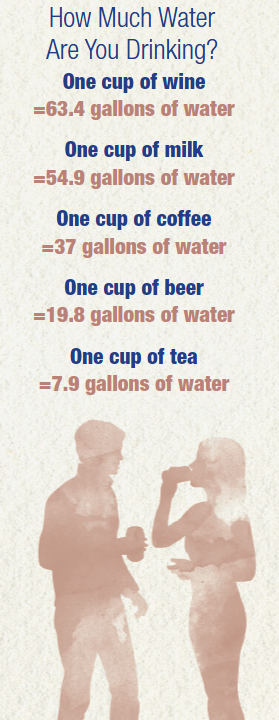

The Water Footprint Network estimates that brewing a single cup of coffee requires 37 gallons of water, when the full costs of production and transport are factored in. Usually it takes two cups of coffee to get the creative juices flowing; with seven days in front of the computer, that’s already more than 500 gallons before delivering a first draft.

Taking into account the water needed to build the computer, power and heat the home office, grow the trees to make the paper, drill the gas to shuttle the car to interviews, and ultimately, to produce the ink and run the printing presses, this single 1,200-word story could easily use more than 10,000 gallons of water.

“It’s time to start thinking about the water embedded in a product,” says Amelia Nuding, water/energy analyst at Boulder-based Western Resource Advocates. “It’s not something most consumers think about in daily life.”

Much like the more established notion of a carbon footprint, a water footprint is less an exact science and more a conservation tool aimed at increasing consumer awareness. Developed in 2002 by Arjen Hoekstra at the UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education in the Netherlands, water footprinting was designed to trace the direct and indirect use of water with the intent of comparing regions across the globe.

Technically, the equation calculates two indirect water usage components—agricultural and industrial—and adds the total to the direct water consumption of a nation. Unsurprisingly, China, India and the United States round out the world’s largest water footprints, accounting for about 39 percent of the planet’s consumption, according to the Water Footprint Network, a Finland-based organization directed by Hoekstra.

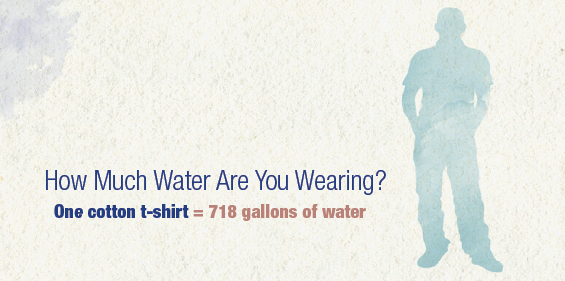

However, international water footprint comparisons are not cut and dry. Global trade means only a percentage of goods produced using regional water supplies are actually consumed in the country where the water is withdrawn. While the Water Footprint Network attempts to factor this into its calculations, water footprints can’t account for water consumption’s impacts on diverse, local ecosystems. For example, water used growing organic cotton in China has a different impact on the region than the same amount of water used growing organic cotton in Turkey. Production in regions with less available water is more costly to the environment, yet that cost can’t be accounted for in dollars and cents.

“It’s important to know how much water is used to make a product and to understand water scarcity in those regions,” says Nuding, who honed her knowledge on the subject as a graduate student, researching water footprints in clothing manufacturing for outdoor retailer Patagonia.

At this point, individual states in the U.S. aren’t calculating their contributions to the national water footprint. Rather, here in Colorado, water footprinting is considered a tool for reducing household water consumption. Although the Water Footprint Network estimates only 5 percent of an individual’s water footprint stems from direct, personal consumption, local experts believe this is the easiest place for Coloradans to get started if they want to tread more lightly. “For the average consumer, they need to begin with looking at the water they use,” says Nuding. “Most folks aren’t going to make a purchasing decision based solely on water.”

Greg Fisher manages demand planning at Denver Water. He suggests examining consumer choices within the home, starting with water-reliant appliances. With the best choices, residents can save thousands of gallons over the next 40 years. “I always look at this from a basic behavioral level—are you going to flush 5 gallons or 1.28 gallons per flush?” says Fisher. A high-efficiency washing machine uses an average of 13 gallons per load, compared to the nearly 40 gallons required by a traditional machine, explains Fisher. Adding aerators to faucets can decrease the amount of water flowing from the tap by up to 50 percent with little noticeable difference to the user.

Denver Water’s website has a handy tool for tracking its customers’ water use, charting individual households’ history of consumption with a simple bar graph. The city of Boulder takes the concept further by giving each household an actual water budget. A single-family household gets 7,000 gallons per month before rates begin to climb. The program, which started in 2009, has resulted in lower usage. “Most customers are staying within budget,” says Russ Sands, water conservation program manager for City of Boulder Utilities. “They see it on their bill and know if they stay on budget they pay less.”

Of course no water audit would be complete without investigating the biggest source of household water consumption—the lawn. Denver Water estimates that 52 percent of its customers’ household water is used for outdoor watering. How much is that lush lawn worth? For some consumers, the cash cost incurred by steeper utility rates is a deterrent. For others, the environmental cost is more effective. “Do we really want to take water out of our rivers to water our lawns?” asks Nuding. “Once you look at it in a water footprint context, the larger picture becomes more significant and we can see the implications of individual choices.”

As a water/energy analyst, Nuding also emphasizes understanding the impact of power sources on water supplies. “Consumers can’t choose how they get their energy delivered,” she says. “But it is important to think about how much water is used and its implications for the future.” She notes recent agreements by Xcel Energy to transition away from coal-fired plants toward natural gas plants as a positive step for Colorado’s water resources.

As for consumer choices, Nuding encourages Coloradans to factor in the ecological impact of their purchases. Whether shopping for a new ski jacket or a taking a quick trip to the grocery store, find companies that are cognizant of and working to reduce their own water footprints.

The Colorado Water Conservation Board (CWCB) has seen children catching on to the impact of indirect water use in its community outreach. “They already know some ways to save water at home,” says Ben Wade, water conservation coordinator at the CWCB. “But when you show them how much water it takes to build a car—building the frame and the tires—the message starts to sink in; you see they really get it.”

Ultimately, getting kids (and their parents) to see water as a finite resource that requires trade-offs is something a water footprint can help illustrate, adds Veva Deheza, chief of the CWCB’s water conservation and drought planning section.

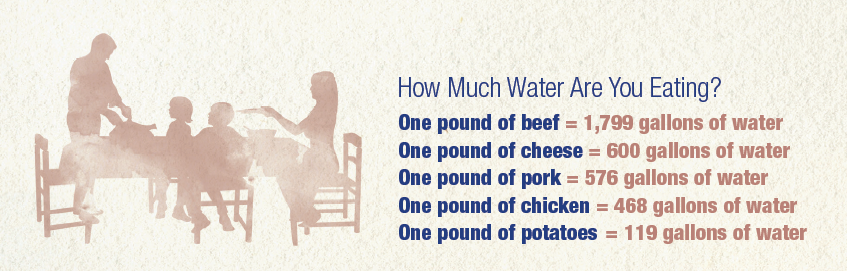

From investigating big-picture choices such as our energy sources to simply installing a $10 aerator on a kitchen faucet, consumers can see their actions impacting water supplies. Incorporating a meatless dinner on the menu once a week can make a difference. Switching from coffee to tea, with a footprint of nearly 30 gallons of water less per cup, could have saved 400 gallons of water in the writing of this story alone.

Still, coffee is a better choice than wine, which would’ve added more than 350 gallons to this story’s water footprint, and who knows how many more drafts would’ve ensued?

Print

Print