How will Colorado ensure its development boom is supplied in a way that’s both sustainable and protects end users?

On a bright spring morning in 2006, Jack McCormick came in from watering the horses outside his rural home in northwestern Douglas County and found his wife, Lois, perturbed. The McCormicks live on a five-acre lot 20 miles south of Denver, in a 29-home subdivision called Plum Valley Heights. They rely for water on a 700-foot-deep well that taps the Denver Basin Aquifer, a non-renewable underground reservoir whose decline in recent decades has mirrored a boom in the South Metro area’s population. On that morning, Lois was in the shower as Jack filled the horses’ stock tank, but the flow from their well wasn’t strong enough to supply both uses at once. Suddenly, Lois’ shower ran dry.

“I came in and she was pretty upset about it,” McCormick recalls. “Of course, when the horse tank was full, the shower started flowing again, but as I was filling it she lost her water!”

When the Douglas County Commissioners approved the Plum Valley Heights subdivision in the late 1970s, they did so without much concern for the long-term sustainability of the individual groundwater wells that made up the development’s water supply. Back then, no law required that the sufficiency or longevity of a water supply be weighed when planning a development, and while a 1973 state law theoretically prevented the McCormicks from pumping more than 1 percent of the groundwater from beneath their land each year, the aquifer’s complex geology made that number tough to pin down.

Today, much has changed in the world of land and water planning: A 2008 state law, House Bill 1141, requires local officials in Colorado to consider the adequacy of a development’s water supply before approving it, and Douglas County regulations now mandate that developers in the county’s northwestern corner supply their projects with water that’s 100 percent renewable—replenished annually by snow and rain. Yet special districts, which supply water to many of Colorado’s unincorporated areas and some municipalities, lack authority under state law to decide where and how development unfolds within their boundaries. And none of these changes have helped the McCormicks, who have coped with declining groundwater levels since they bought their home in 1989 by drilling a new well and then lowering their pump four successive times. Although a renewable water supply is now in sight for them, it will come at a steep cost: Last November the McCormicks voted with 265 of their groundwater-dependent neighbors to join the Roxborough Water and Sanitation District, a Littleton-based water and sewer provider, for a fee that could climb to $60,000 per household.

Roxborough is a small district that leases excess South Platte River water from the City of Aurora, then pipes it to some 3,400 homes and businesses southwest of Plum Valley Heights. Officials there say bringing on new ratepayers could help lower costs for existing customers. Still, Plum Valley Heights and its neighboring subdivisions will soon be buying water from an entity that had no involvement in their original design or approval. It’s an expensive, last-ditch solution that would make most land and water planners cringe, and it begs the question: If Colorado’s population grows by three to four million people over the next few decades as the State Demographer’s Office projects, can land use planners and water providers work closely enough to ensure they’ll have the water they need to adequately support that new growth?

Show me the water law

In Colorado, local governments employ a wide range of approaches to ensure that new development is served by an adequate water supply. H.B. 08-1141, also known as the “show me the water” law, requires that local decision makers weigh the “quality, quantity, dependability and availability” of a developer’s proposed water supply, and many cities go further by requiring specific quantities of water before approving development or annexing new land into their boundaries.

Cities like Greeley and Longmont, for instance, mandate that residential developers provide their city water departments with three acre-feet of water for every acre of land developed or annexed, including any water historically used to irrigate the land where they wish to build. According to Longmont Public Works and Natural Resources director Dale Rademacher, the three-acre-foot rule is designed to secure sufficient water for a variety of potential land uses and building densities while granting extra water for public uses like parks.

“We’ve had that in place since the mid-1960s, and it’s worked incredibly well,” says Rademacher. “It has put the city in ownership of some of the most senior water rights on the St. Vrain River, and that puts us in a very good position: If the St. Vrain gets low, the city is often able to keep diverting.”

Longmont, Greeley and many other cities allow developers who can’t meet their water requirements with historic, on-site water rights to pay so-called “cash-in-lieu” fees or to provide the city with water rights from other sources. However, both Greeley and Longmont restrict the type of water they’ll accept to prevent developers from simply buying up and drying nearby agricultural lands. Longmont, for instance, will only accept offsite water from sources like Lake McIntosh, west of the city and fed by the St. Vrain, or the Colorado-Big Thompson Project, the transbasin diversion that diverts from the Colorado River headwaters in Grand County. Both make water shares available through purchase or lease agreements.

In addition to providing water rights, developers in most communities must also pay into existing water systems. Greeley charges plant investment fees to help cover water treatment expenses, along with tap fees to pay for new water and sewer lines that connect to existing infrastructure. In recent months, some developers have expressed concern that high water-related fees could push development outside of city limits into unincorporated areas of Weld County, unintentionally encouraging sprawl.

“The more a municipality adds up the fees, the more it drives development to the outlying areas,” says Greg Miedema, executive officer for the Home Builders Association of Northern Colorado. “In this economic recovery we haven’t seen much wage growth, so if you continue to ratchet up the cost of development fees and everything else, home ownership could become a luxury in Greeley.”

Yet Greeley officials say they’ve actually seen a steady increase in development activity within the city over the last several years, even as water-related fees have grown, and a fee study completed at the end of 2014 suggested that Greeley’s development fees were comparable to those of nearby municipalities. While Greeley’s water-related impact fees of $11,000 per single-family unit were higher than fees in Longmont and Loveland, for instance, they were much lower than Boulder’s $16,807 in fees or Thornton’s $20,515. Whether Greeley’s water fees are high enough to push growth into unincorporated Weld County remains an open question: Although suburban-style residential development is allowed in some parts of the county, building the infrastructure to serve an unincorporated area carries significant costs of its own. And, for its part, the county could downzone to maintain a rural density if it chose.

Home of the planned Sterling Ranch subdivision. Photo: Matt Staver

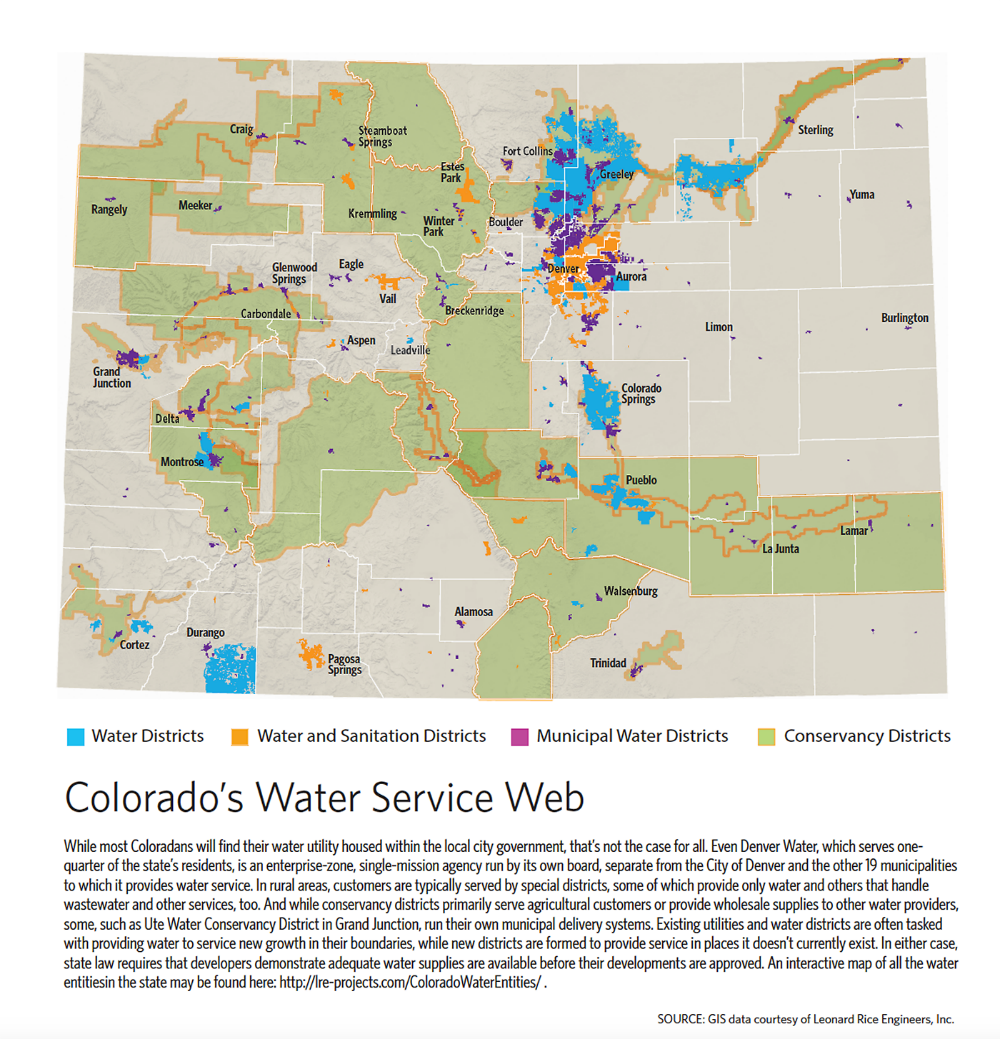

Coloradans in places like unincorporated Weld County who aren’t served by municipal water providers often buy their water from special districts, quasi-municipal taxing authorities set up to provide services that local governments don’t. Although many special districts are established to serve growth in unincorporated areas of the state, others operate within municipal boundaries, carrying out public functions from fire protection to street lighting. State records show there are 77 water districts and 123 water and sanitation districts now operating in Colorado, along with an untracked number of so-called “metropolitan districts” that provide water service in addition to other amenities.

“Special districts do things that governments either can’t do or don’t want to do,” says Ann Terry, executive director of the Special Districts Association of Colorado. According to Terry, special districts operate in many other states besides Colorado. “Often a city will decide that they just aren’t set up well to provide water service, so a special district will form to do it for them,” she says. Frequently, those districts are founded by developers seeking to enable water service where it doesn’t currently exist.

Although special districts can levy property taxes to support their operations, they lack the authority of municipal governments to regulate land use considerations, like zoning or development density, within their boundaries. When forming, every special district must win approval from local officials—most often a city council or board of county commissioners—for its “service plan,” a basic overview of the district’s intended service area, infrastructure and financial strategy. Local officials have the power to deny a special district’s service plan if they deem it deficient, but because many of them lack expertise in water issues and are eager to see special districts spur new development, these service plans don’t always get sufficiently stringent review.

“The prospect of additional tax revenue is a huge motivation for county commissioners to approve special districts,” says Dick Brown, a lobbyist for the Pike’s Peak Regional Water Authority, a consortium of 15 water providers serving the area around Colorado Springs. “Local officials feel they have a responsibility to encourage economic development, and I would also think that dependent upon the size and sophistication of the county government, they may not have the staff and resources to dig very deep into these [water-related] ideas and concepts.”

In an attempt to bridge this knowledge gap, many local governments require that officials consult with the Division of Water Resources when reviewing service plans, because that agency maintains comprehensive data on the water supply and commitments of every water provider in the state.

“We look at two things: is the water supply adequate, and will [the service plan] prevent injury to other water users?” says State Engineer Dick Wolfe. “Our response is just advisory, but in most cases the local government will adhere to our recommendation.”

Special districts in the water supply equation

The methods special districts in Colorado use to secure their water supplies are as varied as the districts themselves. Some operate their own pipelines, treatment plants and reservoirs, while others buy excess water from municipal utilities or share water and infrastructure with other providers. In Eagle County, for instance, six metropolitan districts originally founded by developers to serve communities like Eagle-Vail, Avon and Beaver Creek partnered in 1984 to create the Upper Eagle Regional Water Authority, linking their systems to enable the movement of water throughout the Eagle Valley and ensure reliable backup water sources.

“Our area has been growing for 50 years, so if our early water boards had just supplied each development singularly, it wouldn’t have turned out as well,” says Diane Johnson, communications and public affairs manager for the Eagle River Water and Sanitation District, which manages the Upper Eagle Regional Water Authority. “Those early boards had to project where they were going to be in the future and combine infrastructure to prepare for future growth.”

Harold Smethills (right) says he already has enough water to supply the entire 12,000-home Sterling Ranch development, which will be constructed over 20 years. Beorn Courtney (left) of Element Consulting helped Smethills blend a water-efficient design with a flexible water sharing and infrastructure plan for the development that will be approved in phases. Photo: Matt Staver

As Colorado’s water supply gets tighter in the face of population growth, drought and climate change, the efficiency gained from sharing resources will likely become increasingly important. With that in mind, the developers behind Sterling Ranch, the new 12,000-home subdivision planned on 3,400 acres near Chatfield Reservoir, opted to create a wholesale water district when it came time to plan their water supply: the Dominion Water and Sanitation District.

Rather than selling water directly to customers, Dominion will provide water to other districts in the area, including a new retail water district within Sterling Ranch, while also partnering with surrounding districts to increase the efficiency of the area’s water supply. For instance, Dominion is helping fund the enlargement of the Roxborough Water and Sanitation District’s existing water treatment plant, an expense that Roxborough would be hard-pressed to afford on its own. In exchange, Dominion will use part of the enlarged plant’s capacity to treat water for Sterling Ranch customers.

“The future of water is in leveraging infrastructure,” says Harold Smethills, president and CEO of Sterling Ranch LLC. “We have to change our thinking from building a water supply to building a water system.”

Several of Sterling Ranch’s principal water sources also epitomize this collaborative approach. The project will rely on surface water from the South Platte River that Dominion acquired through a complicated series of trades, swapping water rights with Brighton and Aurora in exchange for a commitment from Aurora to help supply Sterling Ranch.

In addition to South Platte surface water and a backup supply of groundwater from wells south of Castle Rock, Sterling Ranch will purchase water from the emerging WISE project. Short for Water, Infrastructure and Supply Efficiency, WISE will capture reusable water owned by Denver and Aurora from the South Platte River, pipe it back to Aurora’s Peter D. Binney Water Purification Facility for treatment, then send some of it west to 10 water providers in Douglas County through the recently purchased East Cherry Creek Valley Western Waterline pipeline. When Dominion Water and Sanitation joined WISE, other Douglas County water providers were already working with Denver and Aurora to plan the project in hopes of reducing their reliance on nonrenewable groundwater supplies. To cover the additional burden that Sterling Ranch customers will place on the WISE system, Dominion has agreed to cover a share of previously incurred costs while also helping to pay for its future construction.

Although Sterling Ranch was conceived over a decade ago, as a bricks and mortar project it’s relatively new. Earlier this year workers broke ground on the first of its 12 planned phases. Smethills says he already has enough water under contract or option to supply the whole development when it’s completed 20 years from now, but the design of the project’s water infrastructure will be finalized over time as each new phase is approved.

Temporary roads marks the start of Sterling Ranch’s first phase, which will include about 800 homes. At build-out, nearly 31,000 people are expected to live on the 3,400 acre property, with 1,200 acres reserved for open space. Photo: Matt Staver

“The key is being able to prove the delivery system phase-by-phase, and piece-by-piece,” says Smethills. “If you had to build the infrastructure up front, what you would have is sprawl, since the only thing that could happen would be small projects with individual water supplies. There isn’t a single water provider that has its entire water infrastructure in place for the next 30 years.”

In 2012, Dominion Water and Sanitation was nearly forced to become such a water provider when a state court overturned Douglas County’s previous approval of Sterling Ranch. In his ruling, Douglas County District Court Judge Paul King wrote that by agreeing to review the development’s water system in phases as the project was built, the county had violated H.B. 008-1141’s requirement that new developments prove the adequacy of their water supply up front. Concerned that designing the project’s entire infrastructure ahead of time could render them financially insolvent, Smethills and his colleagues successfully petitioned legislators for a change in state law that allows local officials to decide when in the approval process to review a new development’s water supply, and permits them to approve water plans for multi-phase projects like Sterling Ranch over time. Buoyed by that authority, the Douglas County Commissioners in early 2015 signed off on Sterling Ranch’s first phase, which will include 660 detached homes and up to 140 townhomes. They did so after conducting the same detailed “sketch plan” and “plat” reviews of the project that they’ll do at each subsequent phase, which included signing off on detailed engineering drawings of the project’s water delivery system.

The commissioners’ decision was eased by an offer Smethills made to sweeten the deal, pledging to sell 10 percent of the water he procures for each phase of Sterling Ranch to neighbors who—like the McCormicks in Plum Valley Heights—are eager to transition off of declining groundwater wells. Smethills estimates there are 700 such well owners on the periphery of Sterling Ranch, and he argues that the best way to cover the astronomical cost of bringing them a renewable water supply is—perhaps ironically—to build many more homes in northwest Douglas County and use the proceeds to pay for the necessary water infrastructure.

Although Sterling Ranch’s plans to conserve water and share infrastructure with surrounding providers are creative and even ingenious, some wonder whether the fundamental form of the proposed development—single-family homes and townhomes on individual lots in the suburbs, far from the urban core—is the wrong sort of growth to be perpetuating given Colorado’s water constraints.

“The broader question that people of the state need to ask is: ‘Should we be doing land development in an entirely different way because our water resources are so constrained?’” says Todd Bryan of the natural resources mediation and consulting firm CDR Associates. Bryan formerly worked at the Keystone Center, where in 2014 he helped launch the center’s Water and Growth Dialogue, aimed at assessing and quantifying the water-related implications of varying growth patterns. Results from this dialogue are expected by the end of 2015.

“The goal of the project,” says Bryan, “is to change the question from ‘Where will we get the water to support new growth?’ to ‘If we knew the water use consequences of different land use choices, might we make different choices?’”

Print

Print