Colorado’s rapid growth offers a golden opportunity to merge water and land use.

If Colorado pushes to 8 or 9 million people at mid-century, as demographers say is possible, changes most certainly will occur in how our land is used. How could they not? Today’s population hovers at 5.3 million. While we may not become New York City or San Francisco, a few million more residents means Colorado’s cities, suburbs and country estates will inevitably spill onto today’s farms and pastures.

But how will they spill? And how will Colorado’s existing towns and cities reinvent themselves? Those are among the questions as Colorado peers toward the bottom of its water bucket, trying to calculate how revised land use can help bridge the gap between water supplies and expectations.

“Colorado cannot grow its next five million people the way it did its first five million,” Jim Lochhead, who has lived and worked on both sides of the Continental Divide, now as chief executive of Denver Water, has been known to say. That’s the challenge in a nutshell.

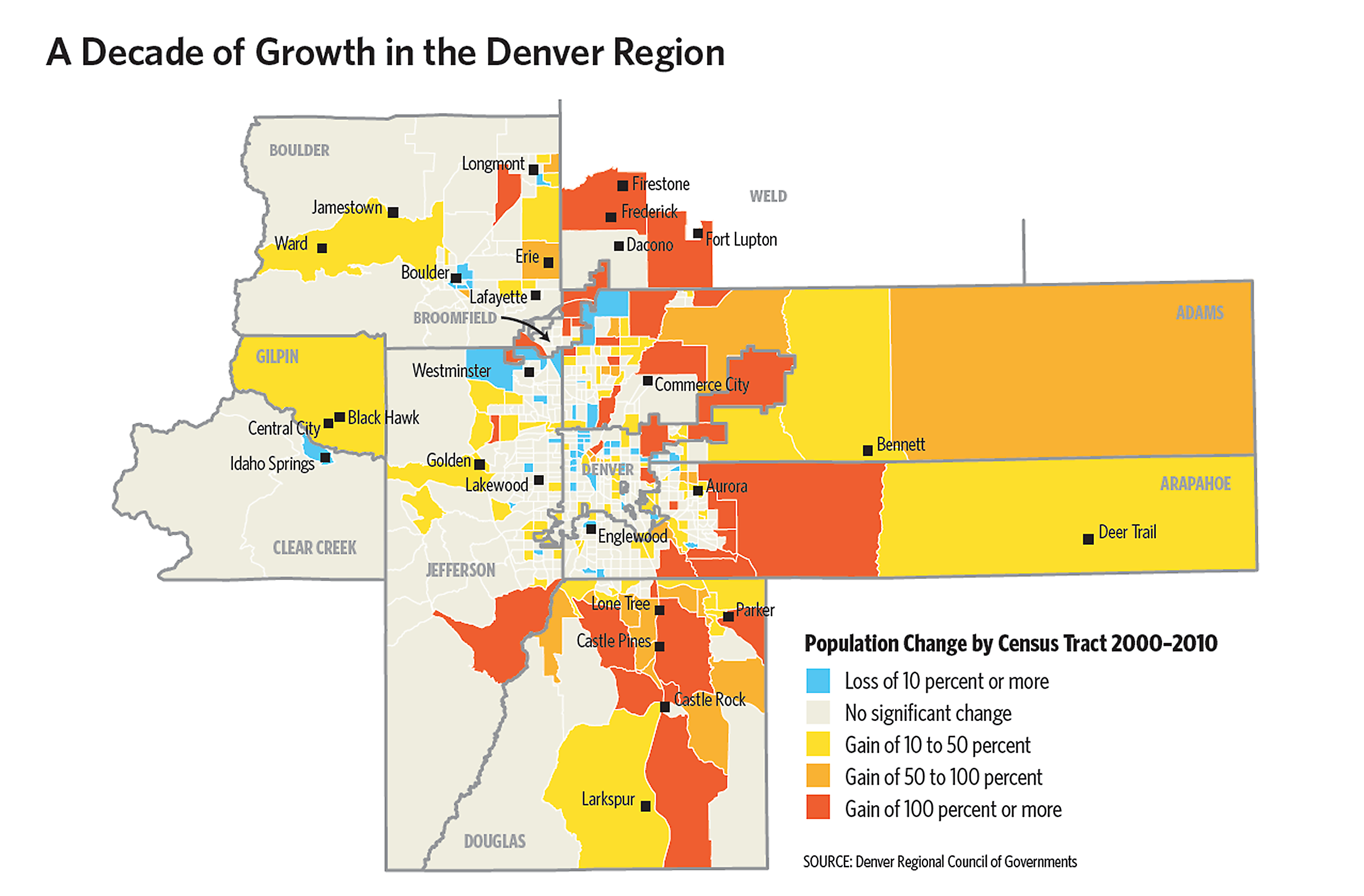

Those next five million people will live in many places. The largest proportionate increases are expected in valleys of the Western Slope. The larger numeric growth, however, will be along the northern Front Range, from Castle Rock to Greeley and Fort Collins, where an additional 2.5 million people—or roughly the existing population of metropolitan Denver-Boulder—could make their homes by 2050, according to high-growth population projections calculated by the Colorado State Demography Office for use in Colorado’s Water Plan.

Not only will that mean new development, but 75 percent of existing housing along the Front Range could be remodeled or replaced by 2050, according to the Brookings Institution, a think tank based in Washington, D.C. It’s a golden opportunity to rethink the way we grow in Colorado.

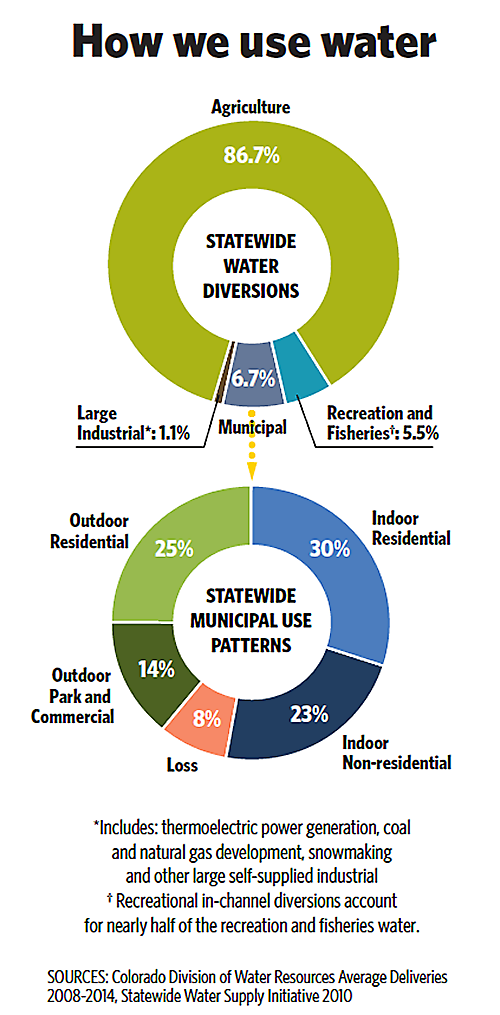

Today’s towns, cities and other domestic and commercial users account for just under 7 percent of the state’s water use. The water to accommodate millions more people could come predominantly from farms or rivers, although there are problems with both. Sales of farm water, if profitable for the individual seller, negatively affect the operation of remaining ditches and rural economies. Mechanisms to allow an expanded sharing economy between farms and cities are being explored, but with no clear resolution.

As for diverting more water from rivers, Colorado’s rivers are already appropriated to the extent that we bump up against interstate compact limitations on all except for the South Platte River during winter months and, somewhat more ambiguously, the Colorado River and its tributaries, the source of 80 percent of the state’s surface water. Because the headwaters are mostly tapped out, to make additional large-scale diversions from the Colorado River Basin would require transport across several mountain ranges and hundreds of miles to the Front Range urban corridor. Infrastructure costs would be enormous, opposition prickly, and the long-term availability uncertain. In examining 112 climate model projections, the 2012 Colorado River Basin Water Supply and Demand Study found an average 9 percent decline in long-term average flow of the Colorado River, at least partly the result of increasing temperatures, with a quarter projecting an even greater decline of 16 percent.

This brings the conversation back to conservation, and how to do more with less. An assortment of water-saving activities have been embraced and promoted by the state’s water providers over recent decades with much success. However, state water planners and environmental advocates say one strategy remains largely untapped, and that is to use the mechanisms of land use planning to build in water efficiency at the outset of all the forecasted new growth.

Land use planning has two levels. First, there is the visioning process, an assessment by a town, city, or county government of how the land should be used, often formalized by a community’s comprehensive plan. The resulting plan is only as good as the regulations created to implement it. This usually comes in the form of a municipal or county zoning code and subdivision and site-plan regulations. Finally, land use planning and regulations succeed only if sustained by the decisions of elected and appointed officials.

They are, at times, ignored, says Greg Hoch, who has worked as a community planner first in Denver and now for several decades in Durango.

In Colorado, as with other states, land use planning and water development have often been overseen by entirely different agencies or local governing boards. Hoch, for example, was a planner in Denver in the early 1970s as the Denver Water Board sold water to the fast-expanding suburbs. Hoch says that, at the time, utility staff were not coordinating closely with planners in those communities. Today, Denver Water provides water to 1.3 million people, more than double the population within Denver’s city limits. In delivering that water, the utility has no direct control over the land use patterns established by the governing bodies of Lakewood, Centennial, Arvada and other customers.

In 2008, Colorado adopted a law addressing a component of this disconnection. House Bill 1141, Concerning Sufficient Water Supplies for Land Use Approval, required that building permit applications for developments of more than 50 single-family equivalents include specific evidence of an adequate water supply. Local governments, however, were granted the sole authority for determining what constitutes “adequate.” As part of this “show me the water” law, consideration of conservation and demand-management measures as well as hydrologic variability was also explicitly required, points out Jim Holway, who directed the Western Lands and Communities project, a joint venture of the Lincoln Institute for Land Policy and the Sonoran Institute, from 2009 to 2014.

But a disconnect between water suppliers and land use planners in many, if not most, Colorado communities has persisted. Consider Larimer County. There, the Fort Collins-Loveland Water District provides water for 16,000 customers in the two cities plus portions of Timnath, Windsor, and unincorporated Larimer County, a 60-square-mile service area. “We just react to whatever has been approved by the cities,” says Mike DiTullio, the district manager. The district’s water comes almost exclusively from Horsetooth Reservoir, typically purchases of water from farms—but not necessarily the farm being displaced by residential and commercial development. “We operate in a free market,” he says.

How to overcome this? “You need community comp[rehensive] plans that say water use and land use are connected,” says Greg Fisher, manager of demand planning for Denver Water. That level of coordination also requires staff-to-staff time, as well as leadership from elected officials, he adds. Only in the last decade has Denver begun to dissolve those barriers. Fisher predicts far more collaborative efforts between land use and water planners in the next few years, such as integrating water supply and demand considerations into land use planning through comprehensive plans and zoning. “We now have a much better understanding of those opportunities and what we are missing if we don’t establish that link between land use and water,” he says.

Peter Pollock, a fellow with the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, also foresees closer integration of land and water planning similar to the integration of transportation and land use planning that has occurred during the last three decades. Traffic engineers always said they could deliver transportation to whatever development patterns were approved, and they usually could. “But at some point, their strategies to continuously increase [transportation] capacities weren’t working,” says Pollock. Now, traffic and land use planners usually work together.

Since the 1970s, Colorado lawmakers have occasionally debated the role of state government in enforcing thoughtful approaches to population and commercial growth. Mostly, the state has remained aloof, staying out of local affairs. This is partially attributable to Colorado’s overall political climate, but also a perceived lack of urgency. “People don’t talk about things that they don’t see as an immediate need,” says Hoch.

Parched summers have a galvanizing immediacy. Such was the case of the smoke-filled drought of 2002. City residents cut back their lawn irrigation and, even after it began snowing again, most of the new behaviors stuck. The draft of Colorado’s Water Plan reported that per-capita demand in the South Platte Basin, outside the metro area, has dropped by up to 30 percent since 2000. And even as the population Denver Water serves has increased more than 30 percent since 1990, total water use has decreased more than 5 percent.

Can our towns and cities absorb more residents without a proportionate increase in water supplies? The evidence in Colorado, and beyond, is that water conservation strategies combined with land planning measures such as higher-density development can dramatically lower the arc of increased water demand.

Can our towns and cities absorb more residents without a proportionate increase in water supplies? The evidence in Colorado, and beyond, is that water conservation strategies combined with land planning measures such as higher-density development can dramatically lower the arc of increased water demand.

“Urban water conservation is a huge success story,” says Douglas Kenney, director of the Western Water Policy Program at the University of Colorado Law School. “Denver is a great example, but so is virtually every major city in the West. It shatters the notion that population growth equals water demand growth.”

Rising prices for water may be spurring increased density of development. In February, a unit of Colorado-Big Thompson Project water—delivered via Colorado’s largest transbasin diversion—sold for near $27,000, triple the price of just two years before. The unit at that time equated to just half an acre-foot, bringing the cost per acre-foot to almost $54,000. Brian Werner, spokesman for Northern Water, the quasi-municipal agency that manages the diversion, attributes the high price to growing demand for residential development.

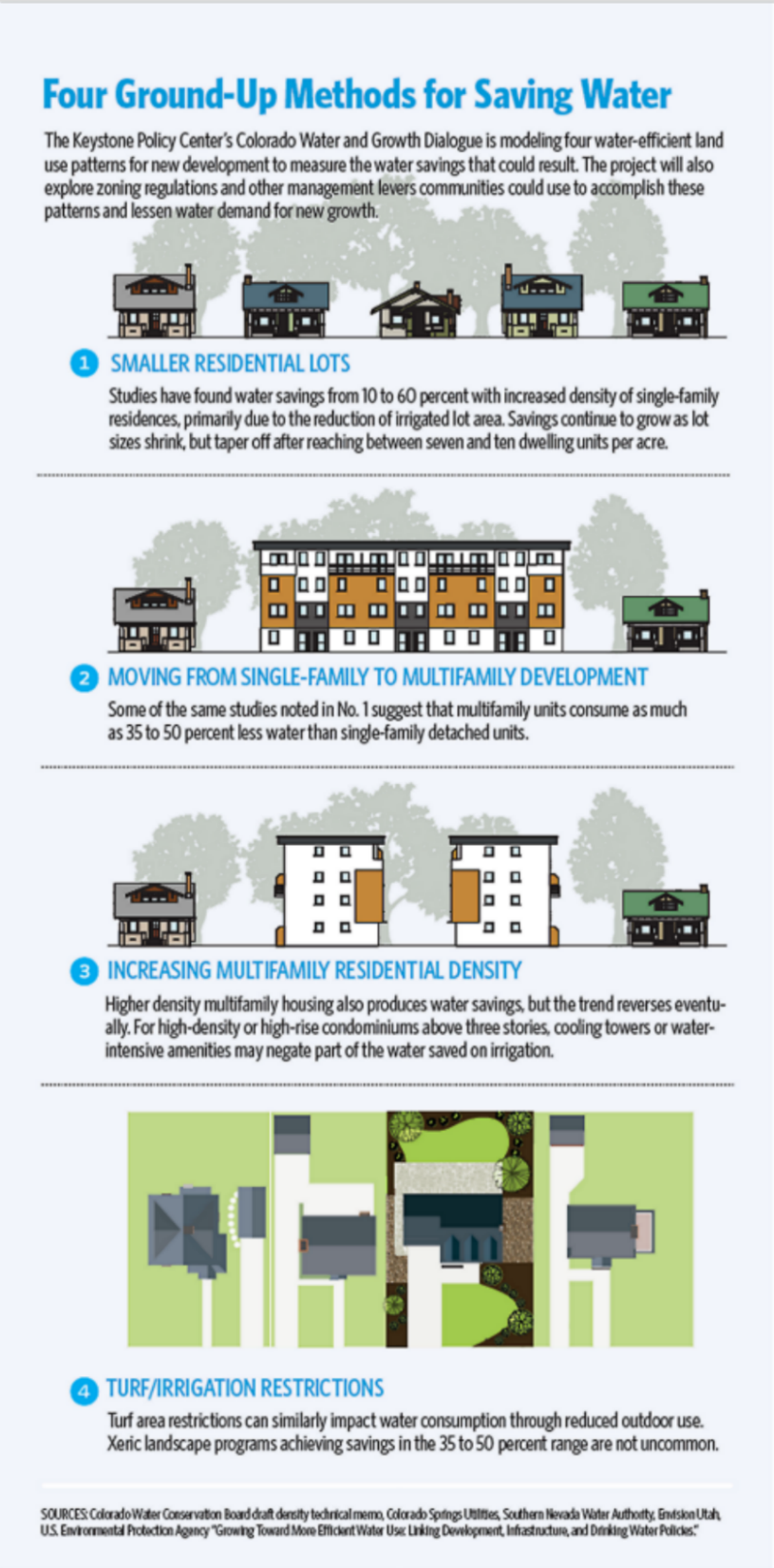

It makes intuitive sense that denser development can save water—and money. A 2010 memo by staffers at the Colorado Water Conservation Board outlined a formula for predicting savings. “Assuming that for single-family homes, 50 percent of the water is used indoors and 50 percent outdoors, water savings can be estimated with each increment of density increase,” said the memo. “The general rule implies that a 20 percent increase in density would yield a 10 percent per-capita water savings.”

If this holds true, the nine-county Denver metro area could realize significant savings. Denver Regional Council of Governments’ Metro Vision 2035 foresees a 10 percent increase in overall density between 2000 and 2035. Already, density increased 5.3 percent from 2000 to 2010, according to the Council’s “Regional Snapshot: Metro Vision 2035 Goals.” By the Colorado Water Conservation Board’s figuring, that 10 percent density increase would mean a 5 percent decrease in water demand, equating to 31,000 to 46,000 acre-feet in savings.

Western Resource Advocates, a Boulder-based nonprofit environmental law and policy organization working in six Western states, also made the case for housing density in its report “New House New Paradigm: A Model for How to Plan, Build, and Live Water-Smart,” published in 2009. “Urban planners and water managers have long known that housing type influences water use,” said the report. In addition to citing recent examples of density’s impact on cutting water use, the report’s strongest evidence came from a 1974 study for several federal agencies by the Real Estate Research Corporation. That 41-year-old study found that “high-density planned development can save 35 percent over low-density sprawl development.”

This intersection of rising water prices and increased density are combined with yet a third wrinkle: new generational preferences. In Greeley’s “2015 Annual Growth and Development Projections Report,” long-range planner John Barnett reports water prices producing greater average density of housing projects, but also suggests that with millenials, those roughly 15 to 35 years old, more inclined than earlier generations to pursue happiness in multi-family housing, the stage may be set for even steeper reductions in per-capita consumption.

Even advocates of tightened land use, however, don’t see an end to single-family homes with lawns. The question, says CU’s Kenney, is whether this should be the default setting. He grew up in Aurora mowing and cutting such lawns. He still does, now in Boulder, but not necessarily by choice. “When you get down to it, I don’t think it’s something many people are attached to,” he says. “I have a lawn because it came with the house I bought. It’s easier to take care of what’s there than to start over.”

Western Slope communities are insistent that land use must become a larger part of the conversation as the state continues to grow. Most striking is the statement by the Durango-based Southwest Basin Roundtable, which calls for a statewide shift in residential water use. Now, it’s commonly 50 percent indoor and 50 percent outdoor use for single-family homes when considered on an annual basis, according to a common metric used by water organizations. The Southwest Basin Roundtable maintains that this needs to be shifted to 60 percent indoors. That doesn’t mean more water use indoors, but rather a substantial reduction of outdoor use. The roundtable wants an even higher standard of 70 percent indoor use for projects enabled by additional transbasin diversions or agricultural dry-ups.

In Aspen and Pitkin County, additional transbasin diversions from the Fryingpan and Roaring Fork River basins remain a lively worry. Two transbasin diversions there still have conditional water rights. Like the Southwest Basin Roundtable, local leaders in this stretch of the Colorado River‘s mainstem believe communities that would pursue transbasin diversions to enable growth should first be accountable to addressing water demand reductions when it comes to how they plan for and regulate that growth.

Laura Makar, assistant county attorney for Pitkin County, says that the first draft of Colorado’s Water Plan aimed too low in its treatment of land use. “It needs to be a stronger section for the water plan,” she says. “Land use drives the timing, location, and intensity of water demands of new and existing population growth throughout the state. There will be increased population, and everything we have seen out there suggests that there will be a water supply gap. Land use planning is one of the most effective ways to decrease that gap.”

A similar theme is echoed in comments made by the Northwest Colorado Council of Governments, which includes Pitkin and four other counties along the Continental Divide, in an April 30 letter to the Colorado Water Conservation Board stressing that Colorado’s Water Plan needs to be seen as an educational tool. “Other state agencies, special districts, and municipal and county governments all have a role in closing gaps,” the letter says. Noting the many powers of local governments, it continues: “Ensuring that new development mitigates the impacts it causes is a long-standing concept in Colorado land use planning.” In response, CWCB staff say the public can expect to see many changes to the land use section (Section 6.3.3) in the second draft of the water plan, released in mid-July, and the final, due in December 2015.

In some places, the water-land connection is clearly being made. Consider Castle Rock, population 55,000 and expecting to someday reach 100,000. Most water comes from pumping aquifers that, even decades ago, had begun to reveal limits. In subdivisions of three-car garages you will still find expansive lawns. But Castle Rock has tightened the faucet: no outdoor watering after 8 a.m. or before 8 p.m. Also, a rate structure based on lot size charges $16 per 1,000 gallons when a pre-determined water budget is exceeded. And like Las Vegas and Los Angeles, Castle Rock now pays water customers to remove turf.

Castle Rock earlier this year also adopted regulations that may be among the most innovative in Colorado. As of April, one project had snatched at the bait of reduced water system development fees, also called tap fees. The Lanterns is to have 1,200 single-family homes on current grazing lands interspersed with oak brush. To qualify for the discounted fees, the Lanterns developed a city-approved water-efficiency plan where a maximum of between 19 and 32 percent of lot size will be devoted to turf, none of it Kentucky bluegrass. Those species of grasses allowed must be able to survive on 19 inches or less of supplemental irrigation per year in addition to the 17 inches of annual precipitation. Kentucky bluegrass needs 24 to 26 inches of supplemental irrigation along Colorado’s Front Range. Inside, only high-efficiency faucets, showerheads and toilets will be installed.

“It’s not over the top or Draconian,” says Scott Carlson, a member of the family developing the property. “We try to make small, reasonable concessions across the entire water use spectrum.” The developer gets lower tap fees, giving the homeowners correspondingly lower-priced homes—and, forever more, lower water bills.

Mark Marlowe, Castle Rock’s utilities director, says the water-efficiency plans are expected to result in new town lots consuming anywhere from 26 to 47 percent less water than those developed in the late 1990s.

Looking ahead, the most significant growth will occur in what might be called the Colorado Boulevard Corridor of Adams and Weld counties. The street bisects the old coal-mining towns of Dacono, Frederick and Firestone before continuing on into corn and wheat fields and, a few miles later, Johnstown and Milliken.

Firestone grew 36 percent during the century’s first decade, tops in Colorado, and Frederick was close behind. No slowdown is expected. Now at 12,000, Firestone expects to hit 60,000 to 65,000. “Water we need at build-out does not exist today,” says Wesley LaVanchy, the town manager. To prepare, Firestone, along with Dacono and Frederick, has a state-approved water conservation plan on file, even though it wasn’t required for water providers operating at such low volumes. LaVanchy points to successes in ratcheting down water use in town parks by 22 to 24 percent and also close scrutiny as Firestone seeks to “foster great communities but at the same time reduce our footprint.” But under such circumstances, one might wonder whether a statewide paradigm shift is needed about what constitutes build-out: Is it when the land runs out or the water?

This is clearly just the beginning of the conversation, somewhat art and not much science. For example, what constitutes a large lot? What about what some call hobby agriculture, the five-acre horse pastures? And do the outer-ring suburbs with their three-car garages also devote more land to water-intensive landscaping—or perhaps less? Colorado lacks any repository for such information. Even Denver Water, the state’s largest water provider, does not break down water use on a per-capita basis on a neighborhood scale, which would be instructive for planners willing to compare water use by various residential land use types. It would also be useful for establishing baselines and setting clear water use reduction targets in planning documents.

This absence was detected even in the 2010 Statewide Water Supply Initiative report. Such data, the document noted, would be “necessary so that developers and city and county planners can understand what the best management practices and methodologies are, and reliably how much water savings they could expect.”

Pitkin County and others go beyond and envision a clearinghouse for best practices. Many small communities are hard-pressed to figure everything out by themselves. But even in plan-heavy mountain communities, there’s little heart for state-down mandates.

That begs the question of whether you can have meaningful results without state mandates. But when Sen. Ellen Roberts, R-Durango, proposed just that last year, limiting lawn sizes in projects dependent upon buy-and-dry water transfers from farms, the bill was quickly watered down. Instead, a legislative interim committee in August 2014 heard repeated testimony from water providers against a one-size-fits-all approach.

Roberts was more successful in 2015 with H.B. 008. Signed into law on May 1, the bill applies to water providers serving 2,000 acre-feet or more annually who wish to seek state financial assistance and must first file a water conservation plan with the Colorado Water Conservation Board. The law requires providers who submit new or updated water conservation plans to the state to include land use strategies as part of their effort to rein in water demand. The law also directs the CWCB, in coordination with the state Department of Local Affairs, to develop and offer free trainings to local planners and water providers about what constitutes best practices in merging the two realms.

Numerous providers will be impacted by the new law: Of the 70 or so water conservation plans currently on file, only a handful specifically call out land use planning strategies, says the CWCB’s technical conservation specialist Kevin Reidy, who will be updating planning guidance documents and working with DOLA’s Community Development Office to plan trainings in response to the new directive.

The Keystone Policy Center is also trying to move the conversation along through its Colorado Water and Growth Dialogue. Since early 2014, the dialogue has convened meetings of 25 individuals from the land and water planning fields as well as economic development organizations. Their charge is to identify land use patterns and incentives that will save water and still deliver housing products that consumers find attractive, says the Keystone Center’s Matthew Mulica, who is leading the effort. Using customer data from Denver Water and Aurora Water overlaid with the Denver Regional Council of Governments UrbanSim forecasting tool, the Keystone Center is working to conduct model runs looking at the water demand reductions that could be achieved through various land use strategies. Alternate scenarios such as climate change impacts will be layered on as the project unfolds. Having actual, comparable data about growth and its water use implications could help overcome some of the disconnect between water providers and planning departments.

The aim is not to rip out lawns from every property, says Mulica. “But for every person who would say, give me a better option, I will jump on it. I would like to frame it as choices.”

Pausing, Mulica pointed to the calls for preservation of water for agriculture, for municipal growth and, of course, water in our streams. It’s politically savvy language, he says, but masks the central reality that Colorado has a zero-sum water game. “We are going to have to set some priorities, make some choices, and we need to do it in smart, strategic ways.”

Print

Print