Meeting Today’s Needs With an Eye on Tomorrow

North St. Vrain Creek flows placidly along Apple Valley Road on a blue-sky April day amid the commotion of large trucks and track hoes working to reshape its banks. Seven months earlier, in September 2013, driving rains flooded the creek to nearly 10 times its typical volume and caused it to rise more than 5 feet in barely 24 hours, chewing up sections of U.S. Highway 36, the adjacent roadway between Lyons and Estes Park. In Apple Valley, a small side canyon off the highway, the swollen river uprooted and inundated houses and buried cars as it carved a brand new channel.

The close proximity of houses and the highway to the river not only left them vulnerable to damages, but also compromised the natural function of the North St. Vrain’s floodplain. Although the consequences to homeowners’ properties—“They took a huge, huge hit,” says consultant Jeff Crane, working on behalf of the Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT)—are still visible in spring, an “unprecedented” recovery is in motion, Crane says. In the aftermath of the epic flood, the Colorado Department of Transportation, Central Federal Lands Highway Division of the Federal Highway Administration, and Colorado Water Conservation Board (CWCB) are partnering to avoid similar outcomes in the future, tapping cooperation between highway engineers, river restoration scientists and local landowners.

Where Apple Valley Road connects with the highway, CDOT is blasting away bedrock and widening the highway shoulder—by as much as 60 feet in some places. In those stretches, crews are using cobble and rock to create stairstep vegetated benches between the river and the road to accommodate varying flow levels. They’re placing rocks and tree root wads along banks to build contours that enable the creek to meander and diffuse energy. These natural features, which utilize the blasted bedrock as well as dirt and logs uprooted during the flood, will stabilize the riverbanks and protect the road from the next major flood, while also creating habitat for fish and other aquatic species.

“The river affects the road, and the road affects the river,” says CDOT engineer Abra Geissler of her agency’s somewhat unusual interest in and support for river restoration. “Stream stabilization doesn’t just stop at the [highway] right-of-way, so we have involved landowners and taken a kind of holistic approach.”

With last fall’s floods, opportunity has followed tragedy. Recovery efforts have meant a chance to upgrade and restore both river systems and infrastructure, which haven’t always functioned in harmony. Initiatives to protect property and lives in the short term are feeding into long-term plans to reduce flood risks while also restoring the natural patterns and functions of rivers.

Terry Plummer shows off Left Hand Ditch Company’s newly reconstructed dual diversion structure for its Table Mountain and Bader ditches west of Niwot in early April 2014. The ditches are part of Left Hand’s system to deliver water to approximately 15,000 acres of farmland. Photo By: Kevin Moloney

The vision is a herculean one, requiring the coordination and cooperation of scores of federal, state and local government agencies, businesses and conservation groups, and thousands of landowners—all with slightly different interests but a common goal of improving flood resiliency. The project unfolding along Highway 36 is a prominent, initial example of what that cooperation might look like and the results it could produce.

Even as the desire is there to improve the resiliency and function of pre-flood structures and stream channels, managers and officials racing to restore crucial water supply infrastructure or mitigate flood hazards prior to the 2014 spring runoff in many cases discovered their options were limited, not only by the time crunch, but by funding and permitting stipulations. So they’ve hustled to ensure the safety of and water delivery to many thousands of people and acres of farmland, in some cases installing temporary measures that can be replaced or retrofitted down the road.

Short-Term Recovery

On the night of September 12, 2013, Terry Plummer found himself racing along Left Hand Creek as the rains came down and the floodwaters came up. The vice president of maintenance and operations of the Left Hand Ditch Company, headquartered in Niwot, directed crews to build berms to keep the river from breaching its banks and to divert water that threatened homes and water delivery and supply structures. As the rain kept falling, Plummer and colleague Joel Schaap hurried to see how the South St. Vrain diversion was holding up when the debris-swollen river spilled onto the road in front of them, halting their frantic efforts.

The flood surge stranded Plummer and Schaap on a road for six hours and left behind a path of catastrophic damage. Plummer endured the unnerving flood peak, but his frenzied efforts had just begun. During the following week, he scrambled nonstop to line up construction crews and contractors to mitigate hazards, to bring water supply operations back online, and to survey the damages. “We went straight to work,” he says. That’s been the story for water and flood managers across northern Colorado, who after more than nine months have yet to stop working.

On-the-ground response began before the September 2013 floodwaters had even subsided. Local ditch companies and water districts supported shareholders and neighbors during the flood, building berms to protect properties as rivers sprawled into plains of mud and debris hundreds of feet wide. County, state and federal emergency managers, and National Guard troops focused on saving lives and delivering aid to victims. As immediate threats diminished, officials shifted to assistance and recovery phases, analyzing damages and lingering risks and coordinating relief and repairs.

After an official disaster declaration by President Obama on September 14, federal managers began following the National Disaster Recovery Framework, developed in 2011 to provide a flexible and collaborative approach to recovery. Under the framework, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and other federal agencies deployed staff and resources through the Joint Field Office in Centennial to complete an “advance assessment,” evaluating recovery challenges and assistance needs in the affected counties.

The first step was to identify “exigent,” or emergency, projects requiring immediate attention and then to provide technical support, such as mapping and imaging of channels, to inform recovery efforts and mitigate future flood risks. The list of immediate hazards included unstable banks, sediment deposition in channels, and avulsion—where streams jump their banks to form new channels—which posed short-term threats to properties along transformed rivers and long-term concerns for delivering water for towns and farmers.

By: Charles Chamberlin

To address the exigent problems, managers safeguarded houses, roadways, bridges and other structures next to undercut riverbanks, placing riprap—large boulders, sometimes locked in place with concrete—to stabilize loose or steep sloping banks. The tally of such imminently threatened cases was at least 175. Many private property projects qualified for $14.8 million in funds through the Emergency Watershed Protection Program administered by the Natural Resources Conservation Service, a branch of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

While FEMA and the Army Corps provided technical support for stream restoration efforts on private property, irrigators and water managers raced to make emergency repairs ahead of spring runoff, which kicks off irrigation season across Colorado. Not only did managers need to ensure irrigators could receive their shares of water, but they also had to plan for streams’ annual pulse of snowmelt—bolstered this year by a bountiful snowpack. That runoff would carry additional high-country debris as well as remaining dirt from the flood that could undo initial repairs and further undermine unstable banks. Some emergency structural repairs started up immediately while others had to wait out winter weather for access.

In the short term, Plummer’s crews and homeowner repairs stabilized banks and removed tons of sand, gravel and woody debris from stream channels in an effort to make room for the spring’s forecasted heavy flows. The runoff would test the effectiveness of such measures.

Since the September 2013 flood, Plummer has directed repairs on 10 major diversion projects and numerous stretches of the river. The Table Mountain and Bader diversions along Left Hand Creek were among those thrashed by the floods. Downed trees, boulders and floodwaters bent back the ditches’ two metal headgates at 90-degree angles as if they were made of paper. Concrete diversion walls snapped like twigs. Sand and debris stacked 6 feet deep in places, making it impossible to tell where the stream channel and ditches once flowed.

Contractors initially waited for the ground to dry out, so they could bring backhoes onto the site to move earth and reestablish the channel after the creek carved a new expansive and terraced floodplain. By early spring, as Plummer oversaw progress on a warm March day, crews had combined the diversions to use a new, single headgate—a cost efficiency—and filled in eroded ground beneath the structure with concrete. To protect the diversion from runoff pulses and future floods, they grouted riprap into the banks to lock the river’s course in place.

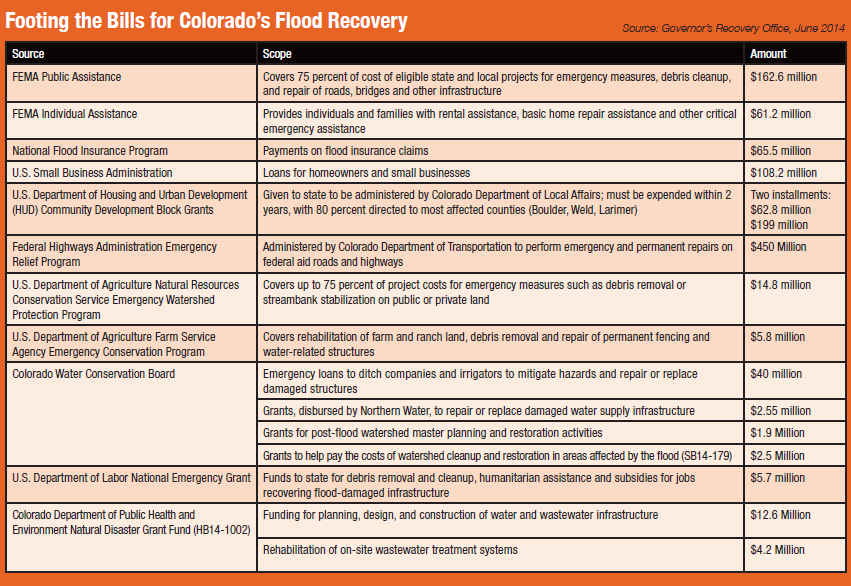

Plummer immediately exhausted emergency funds in the aftermath of the storms, so ditch shareholders agreed to a 40 percent rate hike to cover initial repair costs. The CWCB also jumped in with $40 million in emergency loans for ditch companies and irrigators, offering zero-percent interest for three years. Public assistance dollars through FEMA emerged later to cover up to 75 percent of costs for diversions and structures, which Left Hand and other ditches can use to repay the state loans.

Wade Gonzales, superintendent for the Highland Ditch Company, calls the CWCB loans “a blessing,” which allowed his company to dive into repairs after its main intake diversion on the St. Vrain was “100 percent” destroyed. The Highland Ditch, which runs all the way to Milliken, primarily serves irrigators— and 40,000 acres of farmland—but also provides water to the City of Longmont.

CWCB grants for recovery projects totaling $2.55 million, dispersed in amounts of $20,000 and $25,000 through the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District, have also helped pay to repair or replace damaged water supply infrastructure.

Plummer proudly notes the Left Hand Ditch Company will come in under budget with emergency fixes, and he credits the Army Corps for moving quickly to review permits in order to expedite repairs.

Plummer and others expect tons of sand and debris to continually wash down from the high country in coming years, requiring almost monthly excavations to keep diversions clear and ensure the river stays within its banks. Still, the progress is proof of the success and immense organization surrounding short-term recovery, from planning to funding to implementation.

But the scramble to address imminent hazards ahead of runoff may not even have been the toughest task for managers, especially when weighed against the titanic efforts underway to coordinate long-term recovery spanning entire watersheds. Says Sean Cronin, executive director of the Longmont-based St. Vrain and Left Hand Water Conservancy District, which works with dozens of ditch companies, “Who would’ve thought this would be the easy part?”

Master Planning for Resiliency

A testament to the size and pace of flood recovery, Jeff Crane has racked up 700 miles a week on his truck since last November. The Carbondale-based river hydrologist began serving as CWCB’s contract field project coordinator weeks after the storm, teaming up with and advising recovery initiatives from Coal Creek to the Big Thompson River to Fountain Creek.

Beyond its loans and grants for immediate repairs, the CWCB is backing long-term, big-picture planning and stream rehabilitation. The Colorado Watershed Restoration Program supports the creation of watershed master plans to guide community- and basin-wide projects to rehabilitate rivers’ environmental functions and reduce flood risks. While each master plan is customized for a particular river basin, all are prompted by people’s desire to protect or restore a river system, says the CWCB’s Chris Sturm, who coordinates the restoration program.

In the aftermath of the September 2013 floods, the CWCB approved a special round of grants to communities and coalitions in the 18 counties affected by the floods. Under the guidelines of the special release, a watershed master plan covers collaborative projects that tackle a wide range of basin functions: channel stabilization or reconfiguration, flood control and floodplain preservation, habitat enhancement and wetlands restoration, road and bridge protection, and establishment of recreational features.

Consider the program, which provides money for master planning while requiring matching funds and in-kind contributions up to 50 percent, a nudge and incentive toward comprehensive river planning. “It’s carrots, not sticks,” says Sturm. “What we’re hoping to see is people approach this recovery effort looking at the channel as a system.”

By involving private landowners in discussions with government officials, water managers, scientists and others, master plans— and the coalitions behind them—serve as a forum to set recovery priorities that not only stabilize banks or reestablish stream courses on a single property, but also improve overall resiliency in the event of future floods along entire river corridors. The planning also emphasizes approaching recovery in a way that enables natural river functions during both high and low flows.

Work to rebuild damaged sections of U.S. Highway 36 northwest of Lyons progresses in tandem with improvements to the adjacent North St. Vrain Creek. Photo By: Glenn Asakawa

Across the Front Range, eight basin-wide coalitions, representing nearly every river system severely impacted by the floods, have successfully submitted state grant applications for master planning. Hastening a process that typically spans one to two years, these flood affected communities are pushing to complete their plans in six to eight months. The groups are developing maps that identify sections of floodplain to re-connect to streams and bringing in contractors to carry out projects based on the input of participants and the expertise of consultants and government scientists.

Cruising around Estes Park on a weekday afternoon in early March, Crane checked on the progress of several bank stabilization projects. Along a straightened section of Fall River, several landowners had cemented the riverbanks with riprap to protect their properties from unstable banks. This conventional approach for armoring a streambank is effective at preventing erosion and channel movement that can undermine structures, but it also leads to increased stream velocities that cause a river to incise, or cut down deeper into the channel, where it becomes disconnected from the floodplain.

Instead, Crane often advocates for practices known as natural channel design and “bioengineering,” river restoration techniques that use tree root wads and trunks and strategic arrangements of rocks and boulders to mimic natural forms and features. Such designs also engineer bends and meanders back into straightened rivers in order to diffuse energy from flood flows and minimize risks, while creating pools and spills ideal for trout habitat and kayak runs. The Highway 36 recovery project—with 17 sites along an 11-mile stretch of stream-adjacent roadway—showcases that approach.

The restoration coalitions are building toward similar collaborative projects that blend practical and natural elements—changing some people’s views in the process. “The master plan is a means to a greater end,” says John Giordanengo, who until recently worked for the nonprofit Wildlands Restoration Volunteers, which sponsors the Big Thompson River Restoration Coalition. “It’s not just a great opportunity for restoration, but also for education.”

The speed with which northern Colorado’s flood recovery coalitions have come together to act is nothing short of incredible. The Big Thompson Restoration Coalition formed just weeks after the flood and has brought together 325 stakeholders including landowners, local businesses, local and county governments, and conservation groups. Committees focus on fiscal, technical, and governmental and interagency affairs, as well as education and outreach. Giordanengo, who helped organize and facilitate a similar coalition following the 2012 High Park Fire, says coordinating all the moving parts and varying priorities isn’t easy, but coalition building is about finding compromise solutions that recognize everyone’s distinct self-interests. It’s an ideal model for planning and setting priorities along a river, he says, since what happens either upstream or downstream affects everyone else.

Along the severely damaged Little Thompson River, which runs from above Pinewood Springs to Milliken, a coalition of 380 landowners and other supporters are involved with master planning. Committees meet weekly and monthly, depending on the tasks and workload, and “neighborhood captains” keep nearby landowners in the loop on discussions, plans, and grant and volunteer opportunities.

“Our goal is flood resiliency,” says Gordon Gilstrap of the Big Thompson Conservation District who is facilitating the Little Thompson Watershed Restoration Coalition and whose organization is the coalition’s financial sponsor. “We want to get the river to the point where if there’s another event, it’s not as damaging as this time.”

An Evolving Approach

While the scale of the recovery effort is daunting, the ceaseless efforts of dedicated staff and volunteers are paying off. In the St. Vrain and Left Hand Water Conservancy District, 44 of the 94 ditches and reservoirs sustained damage during the September 2013 flood. For all but four of those diversions and structures, ditch companies have either succeeded in rebuilding ahead of runoff, or are expected to be online at some point during the 2014 irrigation season. In several cases, repairs have incorporated new natural design elements during rebuilding.

At the shared diversion for the Rough and Ready Ditch and Palmerton Ditch downstream of Lyons, repairs replaced a concrete roller dam, which was great at preventing erosion but difficult for fish and dangerous for boaters to navigate, with a long-sloped dam that has a built-in fish ladder. “It will function much better than what was there before,” says Ken Huson, water resources administrator for the City of Longmont, which has a major stake in the system and other ditches in the region, “but it’s also a very good and stable construction that will be able to withstand what will be an interestingly dynamic streambed as it naturally recovers from the flood.”

A similar sloped design was used on the new diversion for the Oligarchy Ditch, another significant supply for Longmont, while renovations on smaller ditches incorporated rock weirs, or low barriers, that still back up water to flow through headgates but provide easier passage. “We feel we need to work with the stream,” says Huson.

In other cases, time and financial constraints as well as regulatory hurdles, whether real or perceived, led to diversion structures being rebuilt almost exactly as they stood in the past. For instance, many federal permits and FEMA funds were understood to be available or expedited only for projects replicating past works, meaning ditch companies preparing for runoff didn’t feel they had much choice. Proposals to rebuild around new channels have also competed with some landowners’ desires to see streams set back in their former paths.

“There are certainly structures that are being reconstructed the way they were 100 years ago,” says Sturm. “It’s a real challenge. You’re balancing this legitimate concern of protecting life and property with ecosystem function of the channel.”

Yet many companies, agencies and local governments have gone above and beyond to help protect private property while considering how they can venture into enhancing river systems’ natural functions.

“Companies are, by and large, interested in sitting down and having a conversation about how things could be built differently,” says the St. Vrain and Left Hand district’s Cronin. “But it’s not as easy as just saying we want to do it differently. What [ditch companies] found out is the time was going to be longer and the money wasn’t available.”

That may mean some of this year’s fixes could get ripped out and renovated or else retrofitted with more natural elements sometime down the road—again, when funds become available. Meanwhile, irrigators and state officials are beginning to think about how they can work with federal agencies so when the next flood occurs, projects to build back for improved resiliency or with added benefit to streams won’t require ditch companies and landowners to wade through a more complicated—and possibly limiting— regulatory process than that for projects reverting to a pre-flood design.

Douglas Mutter spent his career advising recovery programs following disasters, including the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska’s Prince William Sound, the 2010 BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, and 2012’s Superstorm Sandy. He and other proponents of master planning say there’s been “great success” in both rehabilitating river systems and educating water managers. Structures built for later enhancements, such as Left Hand’s Allen’s Lake diversion, which is being reconstructed to accommodate fish passage in the future, are a prime example that short-term action doesn’t have to preclude long-term planning.

Mutter, who retired from the U.S. Department of the Interior last year only to be called in to advise Colorado’s recovery efforts, learned during the course of his career that there’s no cookie-cutter approach to recovery, and what works best for one river system and its communities may not serve others. He emphasizes another essential point, one that flood managers have repeated time and again since last fall: “There’s going to be more big floods.”

“One of the lessons learned is we need to be ready for the next one,” adds Cronin. “We know more now in terms of the responsibility of managing water resources and what makes a healthy ecosystem. It’s a natural evolution.”

Print

Print