Is Safe Drinking Water Finally on the Horizon for Tribes?

Growing up in the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe’s headquarters of Towaoc in Colorado’s Four Corners region, Francilla Whiteskunk would spend her days playing in the dirt just like any kid in the wide-open West. But, she says, there was one thing she never did, no matter how hot and sweaty she got.

“Kids in the city might grab a hose and drink from it. We’d get sick if we tried to do that,” Whiteskunk recalls. Without safe drinking water, Whiteskunk’s father would travel 10 miles to Cortez, Colo. weekly to fill up rubber tanks.

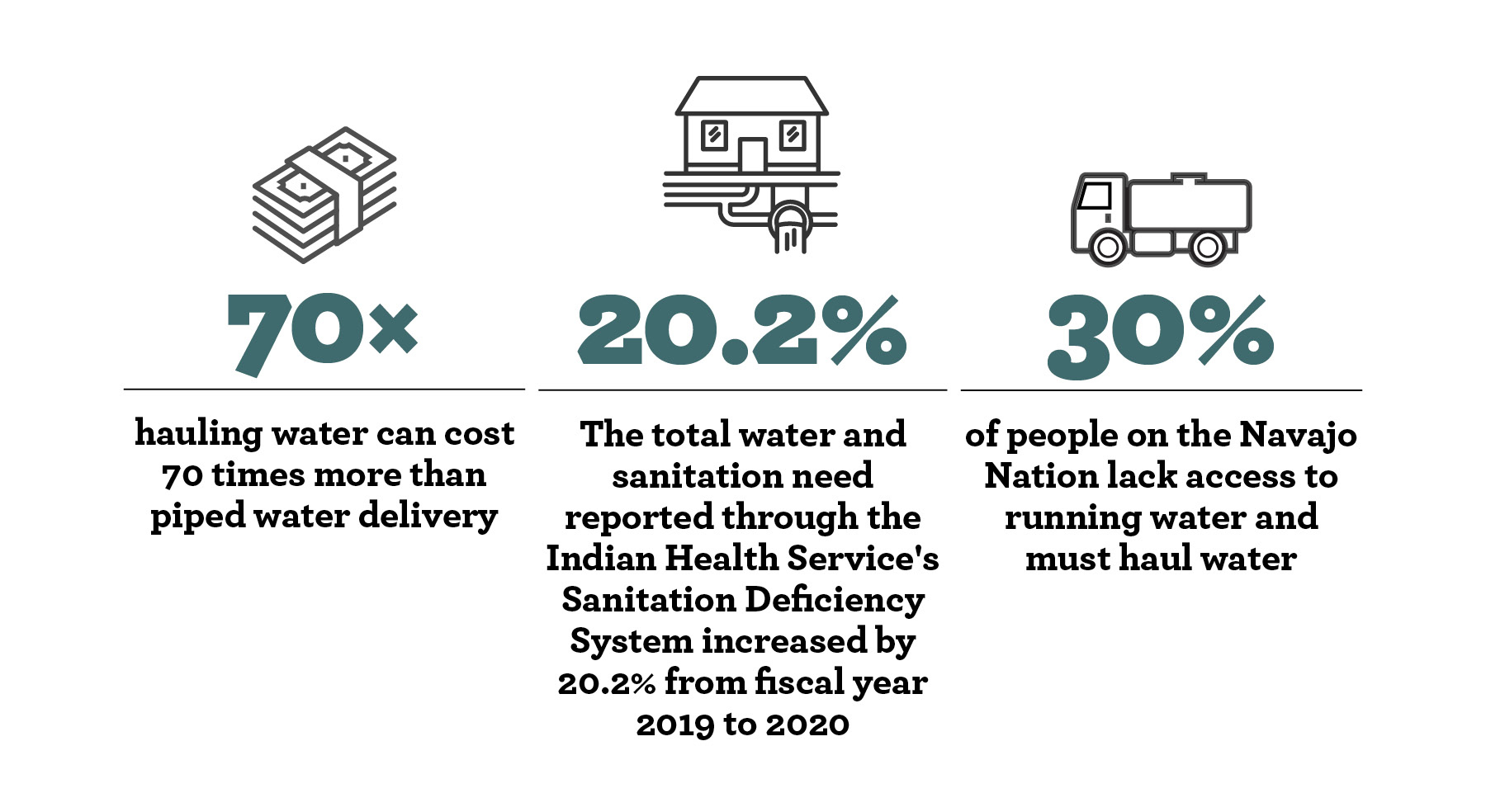

That may sound like the distant past, but for many Native Americans, a lack of safe water is a present concern. Towaoc is now served by a pipeline bringing drinking water from Cortez, but the 250 members of the Ute Mountain Ute’s satellite community in White Mesa, Utah, worry that a nearby uranium mill could contaminate the groundwater that feeds their wells. About 60 miles east of Towaoc, on the Southern Ute Indian Reservation, roughly 15% of residents pay to haul water in, while others don’t trust the water they get due to its odor. Forty percent of Navajo Nation residents, whose reservation covers more than 17 million acres in Arizona, New Mexico and Utah, lack running water. While members of many other tribal nations in the West rely on taps with reported arsenic and uranium contamination.

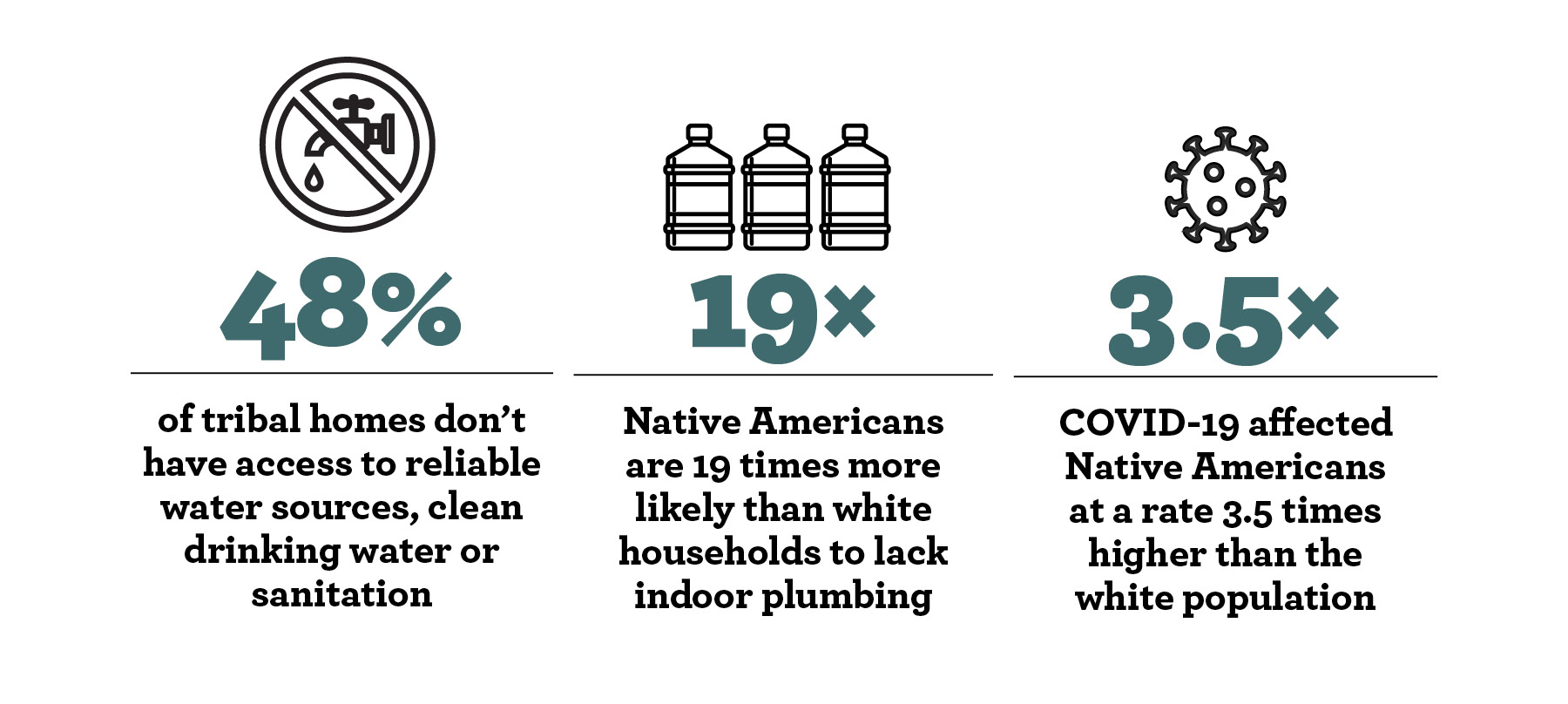

A 2021 report from the Water and Tribes Initiative estimates that 48% of households on Native American reservations don’t have safe, clean water or adequate sanitation. The U.S. Water Alliance estimates that Native Americans are 19 times more likely than white households to lack indoor plumbing, the highest rate of any demographic group.

A lack of running water made Native Americans one of the most vulnerable groups to COVID-19. Heather Tanana, an assistant law professor at the University of Utah, says that should reinforce the government’s “treaty and trust responsibility” to tribes when it comes to water.

“The original treaties say this land is meant to be a permanent homeland, but you cannot have any kind of homeland if you don’t have water,” Tanana says. “This isn’t just a moral or ethical responsibility. We argue that this is the government’s legal responsibility to ensure the tribes have water to thrive.”

The public attention prompted Congress to approve a much-needed $3.5 billion influx to the U.S. Indian Health Service (IHS) for tribal water programs. That could be more than just a health improvement for tribes, says Whiteskunk, a certified public accountant, who now travels to reservations around the Southwest working as a financial consultant to Native-owned businesses.

“Water created a whole new economic resource for Towaoc,” she says. “I look at these communities now that don’t have much going on and I think, if they just had drinking water, it would do a lot of good for everyone.”

How Marginalized Communities Are Left Behind

The IHS, a federal agency within the Department of Health and Human Services, regularly compiles a list of drinking water and sanitation needs for the country’s 574 federally recognized tribes. In fiscal year 2020, the latest data publicly released through a July 2021 congressional testimony, IHS identified more than 1,000 water and sanitation projects with a total cost of $3.09 billion nationwide. In fiscal year 2019 in Colorado, the need was more than $4.5 million.

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, for example, needs to upgrade the mostly clay-lined pipeline from Cortez, which is prone to water breaks in the winter, and wants to install advanced water meters to catch and remedy costly leaks. The Southern Ute Indian Tribe is seeking funding to install indoor plumbing for the many citizens who still rely on water hauling, which can cost 70 times more than piped water—64 tribal member homes rely on water delivery services to deliver water, while hundreds of others haul water themselves.

There are myriad reasons why tribal nations have trailed the rest of the country in clean water access. A long history of racism and underfunding as well as the high poverty rate have left most infrastructure on tribal lands in disrepair. Dispersed rural households are more costly to connect. Reservations are held in trust by the federal government, so tribes cannot rely on property taxes to fund capital investments or operations. And while many tribal water utilities rely on a service rate to maintain operations, tribes typically aim to minimize the burden that high water bills would place on tribal members. Rather, they rely on the federal government and its trust responsibility, which it sees as its “obligation to protect tribal treaty rights, lands, assets and resources.”

Even when houses have plumbing access, the quality of the water delivered is not guaranteed. Legacy mines can contaminate groundwater wells, and aging infrastructure can leave water unsafe to drink or undeliverable. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimates that 86% of tribal water systems comply with health-based drinking water standards, compared to 93% of community water systems nationally.

While tribes can seek funds for treatment plants or other clean water equipment from IHS and EPA, the variety of problems and widespread concerns makes a simple solution hard to come by.

Northwestern University global health professor Sera Young, who studies water insecurity, said plumbing poverty, or the lack of running water infrastructure, can have wide-ranging effects: making households more prone to water-borne illnesses, forcing a diet of unhealthy packaged food, raising stress levels, and creating hygiene problems that make people more likely to miss work.

Water hauling hours and instructions are posted at the Rough Rock Chapter House on the Navajo Reservation, on the road between Kayenta and Many Farms, Ariz. An estimated 40% of Navajo Nation residents lack running water. Photo by Allen Best

A report from DigDeep, a nonprofit focused on increasing clean water access in the U.S., and the U.S. Water Alliance found that the strongest indicator of whether a household suffers from plumbing poverty is race, exceeding even income, urbanization and educational attainment. Native Americans were more likely than any other demographic to face water access issues.

“In the U.S., the same structural violence that we see in so many resource disparities is replicated with water,” Young says. “Marginalized communities are the ones that face the infrastructure problems, although it should be said that water problems are not unique to low-income communities.” For example, Young says, lead contamination is found even in wealthy cities.

“Unfinished Business”

In the late-20th century, the Ute Mountain Ute and Southern Ute tribes negotiated to end some of their water woes. Eventually, the tribes decided to leverage their senior water rights—the Colorado Ute tribes’ water rights date to 1868, when the federal government established their reservation—to secure their future. In a “wet water” settlement, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe agreed to take a later priority date for their water on the Mancos and Dolores rivers, rather than superseding existing communities with more junior rights. In exchange, the tribe received allocations from the Dolores Project that brought drinking water for household use and economic development to the tribal community of Towaoc for the first time. The project stores water in McPhee Reservoir, which feeds a pipeline delivering drinking water from Cortez to Towaoc. The Dolores Project irrigation allocation provided water for the tribe’s 7,700 acre farm.

Mike Preston, who served on the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe’s negotiating team, said the Colorado Ute Indian Water Rights Settlement of 1986, followed by a federal settlement act in 1988 and amendments in 2000, was “transformational” to the Ute Mountain Ute, leading to a new agricultural operation and urban development.

The same settlement gave both tribes water allocations from the Animas-La Plata Project. While the project’s reservoir, Lake Nighthorse, was constructed, infrastructure to deliver water from the reservoir to the tribes was never built. Still today, the water remains inaccessible to the tribes due to lack of infrastructure. The experience also showed how years-long, complex water negotiations that don’t include infrastructure to store and deliver water may not be the best avenue for tribes looking to quickly develop access to safe drinking water, Preston says. Especially recognizing that this is “probably the worst 20-year [drought] period in the Southwest since the Anasazi left.” Preston said efforts to meet the economic and health needs of tribes for running water must be expedited.

Now as governments debate a framework to govern management of increasingly scarce Colorado River water, tribes are elevating their voices. A letter to the U.S. Interior Department from 20 tribes who collectively own rights to about a quarter of the water from the river system said the next framework must “recognize and include support for tribal access to clean water,” among other issues. Still, Preston and many others advocate that access to safe drinking water should be resolved quickly, beyond the confines of river-wide negotiations and beyond the decades-long negotiations of settlements.

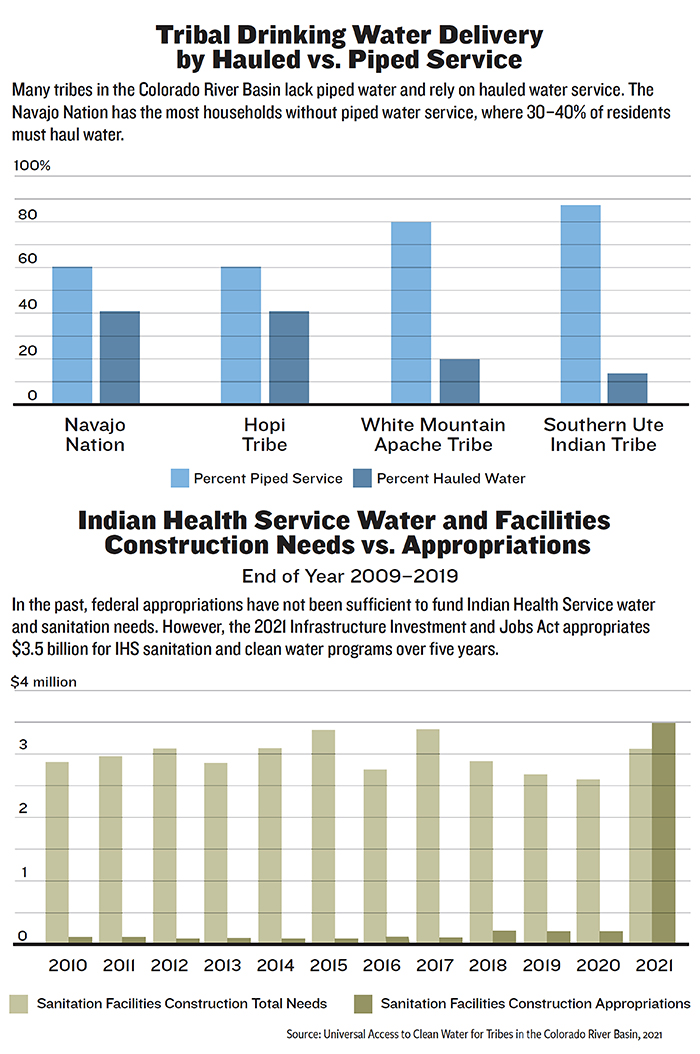

In 1959, IHS was granted authority to address water and sanitation deficiencies on reservations, more than a decade before Congress passed the Safe Drinking Water Act—for IHS, that means delivering clean water supply, sewage, and solid waste disposal facilities. However, funding has fallen short of that directive. While water and sanitation needs have regularly totaled more than $2.5 billion, the most the program has ever been appropriated in a single year is $192 million.

That leaves tribes with few funding options. The EPA offers grants for tribes to comply with its clean water rules, but those generally don’t support new infrastructure. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Rural Development program can back new water and wastewater facilities, as can the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, but both have less money available than IHS. State programs traditionally are less of a focus for tribes.

When Ute Mountain Ute leaders wanted to build a new drinking water treatment plant for the White Mesa satellite community—where residents often complain of stomachaches after drinking tap water—the tribe’s director of planning and development Bernadette Cuthair wasn’t sure where to turn first. A grant writer helped Cuthair negotiate $8 million in USDA funding by breaking the project into a series of small upgrades that complied with the narrow bounds of the program. Navigating that red tape was a headache, but did result in a much-needed advanced SCADA system to monitor the water’s chemical levels.

“People are finally quitting with the bottled water and drinking right from the tap,” Cuthair says.

The Southern Ute Indian Tribe, too, managed to finance a state-of-the-art water treatment facility and expanded water storage pond in 2019. Both are vital to tribal access to clean water, although only 460 households are served by the facility, as the majority of homes on the reservation are outside the reach of the infrastructure delivery system, says Kathy Rall, manager of the Southern Ute Indian Tribe’s Water Resources Division.

University of Colorado senior fellow Anne Castle, who serves on the leadership team of the Water and Tribes Initiative, says that not every tribe has the capacity to chase funding. The initiative is working to enhance tribal capacity and advance sustainable water management; it’s also the group that’s leading the Universal Access to Clean Water for Tribal Communities project. “It’s difficult for tribes, well it’s difficult for anyone, to understand what these different funding programs are and what is best suited for their needs,” she says.

“There’s an increasing recognition that this issue’s time has come and this is part of the unfinished business of our republic,” Castle says.

New Attention Brings Valuable Funding

As the COVID-19 pandemic swept the country, Native Americans were especially hard hit. Federal data showed that the COVID-19 mortality rate among Indigenous peoples was the highest of any demographic. The Navajo Nation experienced more than 52,730 cases and 1,657 deaths as of mid-March 2022.

A May 2020 study published in the Journal of Public Health Management and Practice found that plumbing poverty was the greatest factor associated with Native American COVID cases. Without clean water, households couldn’t wash their hands or even shelter in place safely. Water haulers faced exposure on every trip.

That tragedy, however, had a silver lining. “COVID took the issue of water access and turned it into a matter of life or death,” says Tanana.

Media coverage of the Navajo Nation’s extreme COVID rates brought attention to the government’s lapsed infrastructure promises. The reaction from Washington, D.C., was swift, buoyed by the national Black Lives Matter protests and the government’s stimulus spending. The CARES Act, passed in March 2020, provided $10 million for IHS to install temporary water stations and storage tanks on tribal lands, although restrictions on when the money could be spent limited its impact.

In July 2021, Sen. Michael Bennet, D-Colo., and Sen. Martin Heinrich, D-N.M., introduced a bill to provide $3.4 billion to the IHS sanitation and facilities services and boost funding for other tribal clean water programs. That bill was incorporated into the $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act that passed in November 2021, with a final $3.5 billion over five years for the IHS program.

“I’m pleased the bipartisan infrastructure bill—which is now law—draws heavily on our Tribal Access to Clean Water Act,” Bennet said in a statement to Headwaters magazine. “This is the first step of many to reduce this shameful disparity and help ensure that tribal communities have access to safe, clean water.”

In mid-December 2021, IHS held a consultation with tribes to gather input on how to spend the funds, which will be distributed over the next five years. But experts say the $3.5 billion should represent just a down payment—not the final bill—on clean water access and must be accompanied by technical support.

Of particular importance is operations and maintenance support; many tribes say the problems that led to inadequate plumbing in the first place make it a challenge to stay on top of regular repairs and upgrades. The unique challenges that each tribe faces also mean the federal government needs to work on custom solutions, rather than a one-size-fits-all approach. A Bennet aide said the office is working to enhance technical assistance and operations and management support.

The Water and Tribes Initiative is advocating for a “whole-of-government” approach with officials that can coordinate rather than forcing tribes to navigate the maze of agencies with water authority, as Cuthair had to do. To encourage adoption of such an approach, the initiative created roadmaps for IHS, the EPA, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and for Congress. The Biden administration revived an interagency task force on Tribal Water Infrastructure as part of a broader policy of increasing outreach to tribes. The EPA in October issued an action plan to work with tribes on a sustainable water future, including assurances of greater consultation in water policy, more grant access, and establishing baseline environmental water quality standards for Native American reservations.

Bidtah Becker, a California Environmental Protection Agency official and former Navajo Tribal Utility Authority attorney, says the true measure of the government’s commitment will be in the “sense of urgency” to get shovels in the ground. But the fact that this is even under discussion, she said, reflects the decades of work that have made Native issues more salient.

“In some ways it’s the confluence of Black Lives Matter, climate change and COVID that brought new attention to that,” Becker says. “But I think that’s only part of the story. It’s really about human progress. We are products of our history and everything we have gone through. It’s history that got us to the point where we are now.”

Jason Plautz is a journalist based in Denver specializing in environmental policy. His writing has appeared in High Country News, Reveal, HuffPost, National Journal, and Undark, among other outlets.

Print

Print