For some households, affordability isn’t the main problem. Simply getting water can be the barrier. Some 1.5 million Americans—that’s 463,649 households, or 0.39 percent of all households—live with incomplete plumbing, defined as missing at least one of hot and cold running water, a flush toilet, and an indoor bathtub or shower.

A study published in August 2019 in the Annals of the American Association of Geographers gave an accounting of the scale of “plumbing poverty,” showing a clear racial breakdown: American Indian and Alaska Native households were 3.7 times more likely to have incomplete plumbing, and both black and Hispanic populations had a greater share of households with incomplete plumbing.

“The percentage may be small, but half a million households is a big number,” says Shiloh Deitz, a University of Oregon researcher and co-author of the study. “It’s shocking to a lot of people.”

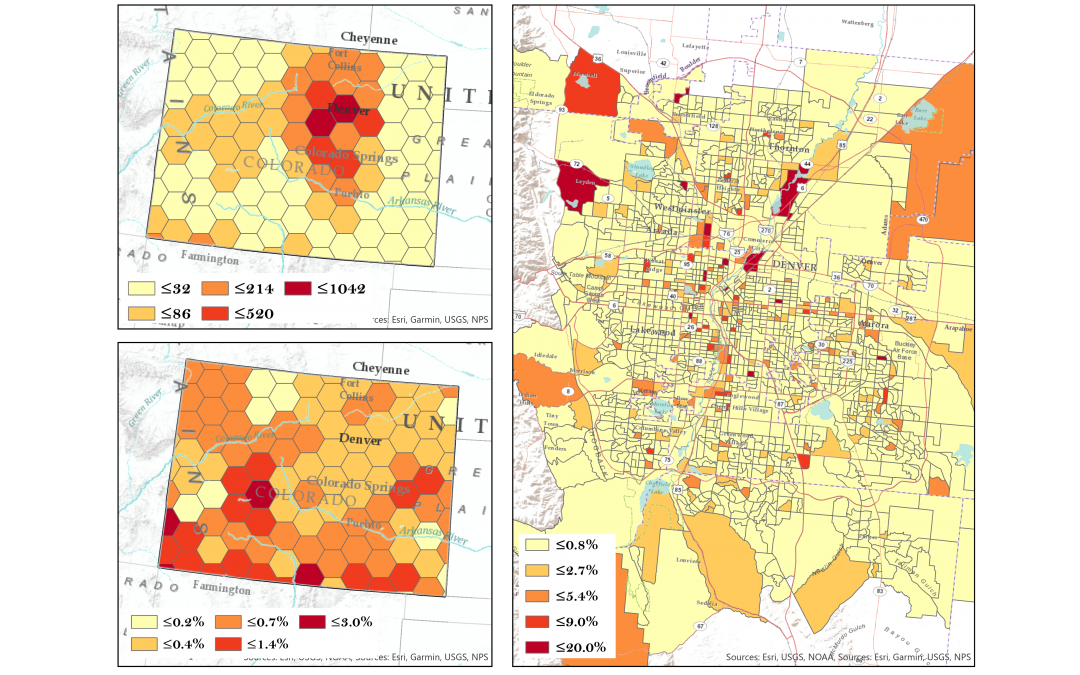

The problem persists around Colorado, especially in rural areas in the southwestern part of the state. A 2007 study in Geoforum also found mountainous areas had spotty plumbing due to “remoteness, construction difficulties, occupance of seasonal housing on a year-round basis and minimal enforcement of plumbing codes.”

According to data provided by Deitz, Denver has the most households suffering from “plumbing poverty” in Colorado. That’s largely because of a concentration of mobile home parks; Deitz found that households were 127 times more likely to lack complete plumbing if they were in a mobile home, suggesting that “nearly everyone” in plumbing poverty was in that situation. (Renters with incomplete plumbing also far outpaced the national average.)

The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE) is responsible for water infrastructure only up to the point of the meter, and only deals with home pipes when it is dealing with unsafe water, meaning plumbing poverty is not considered the agency’s purview.

“When we talk about equity, we mean ensuring that everyone across the state has access to safe drinking water,” says CDPHE communications manager MaryAnn Nason.

Print

Print