Successful outcomes rely on social science and artful engineering.

Even in the best of times it’s difficult to forge a collaborative path when faced with a contentious issue. But in Colorado, where priorities over water use can vary so greatly, reaching consensus can be particularly challenging.

“There are lots of characters in the water business and you are going to end up with some folks who are obstinate,” says Dave Bennett, Denver Water water resources project manager, who has spent more than 30 years dealing with oft-disputed water issues. “Water in Colorado is such a scarce resource and always has been. People are real careful about it, and they can be really defensive about things.”

No two issues are ever exactly the same. But there are some truisms about how to construct a game plan for tackling even the most vexing obstacles and having all parties come away feeling they have achieved a tangible and worthwhile outcome that serves their constituents.

Getting the timing right

A key starting point on the collaborative path is identifying the right moment to begin meaningful dialogue with opposing groups on a given issue.

Todd Bryan, senior program manager at the Denver-based deliberation consulting firm CDR Associates, has spent more than 20 years mediating disputes in the environmental field. He gauges the ripeness of any potential conflict by judging whether it is either “upstream” or “downstream.”

“An upstream problem is where you sort of know you can see the train wreck coming, but it hasn’t gotten there yet,” says Bryan. “You try to get stakeholders together to head that off, because when issues get downstream the conflicts become really intense or there are lawsuits. They are just harder to resolve.”

Bryan says one good way for parties to make sure they engage at the right time is by watching the advocacy sector. If a group makes rumblings in the media about filing a lawsuit or lobbying hard for government intervention on a controversial topic, that should be a red flag that broad discussions between divergent stakeholder groups need to begin, if they haven’t already.

According to Bryan, taking initiative before you get to a legislative or regulatory action is crucial. Once a government entity imposes regulations or laws there are generally winners and losers, and this makes further negotiation unlikely as the party that’s come out on top has little incentive to compromise. That said, certain stakeholders may not be ready to meet until an issue reaches a tipping point.

Mely Whiting, counsel for the Colorado Water Project at Trout Unlimited, cautions that while you can try to prepare for a problem upstream, you need to be equally ready to tackle the issue when it reaches the more quarrelsome downstream arena. “My experience is that there is usually a carrot and a stick situation when it comes to water issues,” she says. “On the one hand, the stick, which is some event with consequences like litigation, has to be there. The carrot is having an alternative collaborative process that is better than litigation.”

When you reach that carrot-stick moment, Whiting says it’s important to be “opportunistic” and begin laying the groundwork for collaborative discussions quickly.

Setting the table

To plan an effective collaborative process, it’s essential to determine the sweet spot wherein all the relevant stakeholders are represented, but the table isn’t so crowded—and loud with differing views—that reaching an agreement becomes impossible. Finding that balance is more art than science.

The general rule of thumb among experts is to begin by being broadly inclusive and later hone in on the most relevant players to continue the nitty-gritty negotiations.“There isn’t a magic number, but often times it might be appropriate to start with a larger number and then winnow the group to a smaller committee representative of all the different, competing positions,” according to Geoff Blakeslee, Yampa River project director for The Nature Conservancy and the environmental representative on the Yampa/White/Green Basin Roundtable.

Reagan Waskom, director of the Colorado Water Institute and chair of the Colorado State University Water Center, believes that a “dual track” approach can be very effective. A public track is organized that allows interested stakeholders to get informed on the details of an issue. Then a smaller group of empowered representatives is set up to propose solutions aimed at resolution.

Bennett agrees with that approach: “Getting a lot of people involved at first [helps] you try to articulate the vision for a collaborative outcome. Without understanding what is important to these stakeholders you won’t get anywhere collaboratively. Once you build trust you can get to the point where folks can see a potential outcome and you can see collaboration as a potential path. Then you narrow down to a negotiation team.”

To create trust among those at the table, MaryLou Smith, policy and collaboration specialist at the Colorado Water Institute, recommends identifying commonalities among parties right from the start.

To that end, Smith often assigns some “homework” before a group convenes. She asks stakeholders to summarize in one page their issue of concern, and what they hope to get out of the process. Equally important, she asks them to include one thing they believe makes them unique from others in the group. She then compiles the statements into a package and sends it out a week in advance to initiate trust building. “They come to the first meeting already having a kick start in understanding who the people are and where they are coming from,” Smith says.

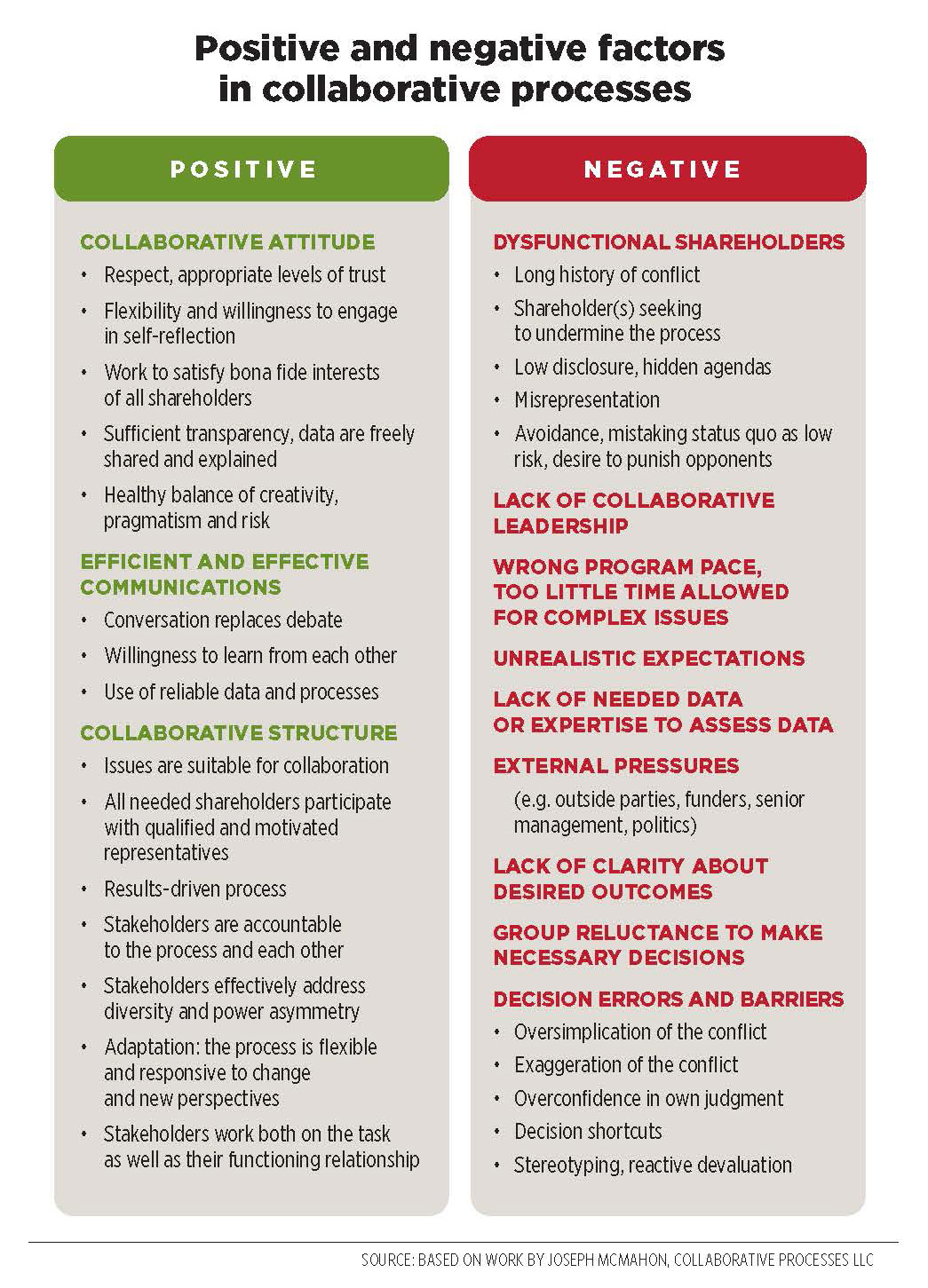

This is just one among many strategies Smith covers in a two-day intensive workshop on “Best Practices for Collaborative Water Decisions” being hosted by the Colorado Water Institute and CDR Associates across Colorado, the first of which was held in October 2015. Like Smith, Bryan is one of the workshop’s trainers. He shares that a facilitation technique to get everyone on track toward serving the common good is by shifting focus from “positional” negotiation tactics to “interest-based positions.” This means helping parties avoid getting mired in articulating a specific belief, such as “I’m against fracking,” over and over again. Instead, the goal is to move the conversation toward the underlying issues that serve a group’s interest, such as “I want to protect groundwater or reduce noise,” Bryan says. “When you identify the interests, you can get from A to B. You have to eventually get there because otherwise one person will restate their opinion and the other party will attack it, and they will continue to bang their heads against the wall.”

Empowering leaders for negotiation

In putting together the group who will hash out any agreements, it’s essential that each member truly reflects the interests of the parties they represent and has the ability to make a deal stick.

“You really want somebody in an upper leadership position who has the respect of their organization and other organizations and has the knowledge and expertise to talk about the problems and tangible solutions,” Bryan says. “If an agreement is reached, they also have to have the ability to get their [organization or group] to bind to the agreement so that they don’t have to go back to get their boss to buy in.”

But what other specific characteristics should you be looking for when choosing a delegate for delicate negotiations?Good communication skills are vital to frame issues. Experience, which provides institutional knowledge about the task at hand, is extremely valuable as well. That said, an ability to empathize with—or at least respect—an opponent’s perspective is essential.“It is important as a leader to put yourself in the other person’s shoes and acknowledge that you are hearing their position and that they understand your position,” Blakeslee says.

Of course, those at the table must always be prepared for a stakeholder representative who is unwilling to budge from his or her position, which may require that others redouble their efforts to build trust.

“Distrust in [a competing] organization is how many come into this process,” Bryan says. “You need to allow relational trust to overcome organizational distrust. One of the things we do is try to get people to know each other so that they realize that they are more complex people than the stake they represent.”

A final point on leadership: A deep bench is important. Water-related negotiations can take 10 years or more to conclude. Over that time, people may change jobs or even retire. While each stakeholder organization may have a primary point person at the table, secondary negotiators or alternates can help avoid a derailment in the process when a key stakeholder has a regime change.

Taking the long view

Rome wasn’t built in a day, and neither are successful collaborations. Waskom says it’s important to recognize that taking slow-and-steady steps is more likely to yield results than quickly bringing people to the table.

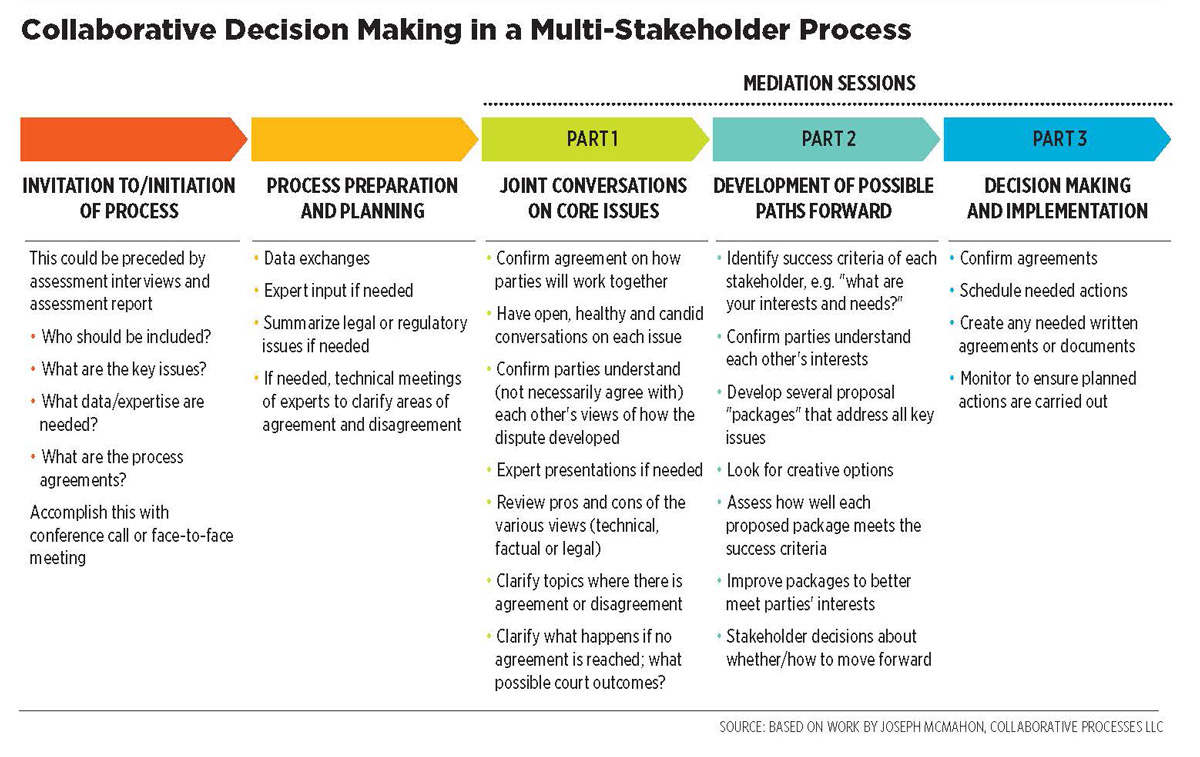

“There is a convening role, a facilitation role, a negotiation role and a mediation role, and all four of those are on a continuum,” says Waskom. “They are different and they are important.” Rushing to set up a first meeting or the second or third isn’t usually the best course of action, he says, adding that each element needs to be carefully considered. Even choosing when and where to hold an initial convening meeting for those interested in the issue should be decided carefully. For instance, finding neutral turf can be very valuable in making all involved feel comfortable.

Once you delve into the process—and negotiations begin wearing on into years—keeping focus on tangible results is also extremely important, according to Whiting. “I have a very strict rule: I don’t engage in groups that get together and are window dressing—they meet and don’t do anything,” she says. “To me, the measure is there must be incremental progress, and it has to be real.”

Whiting points to the River Protection Workgroups in southwest Colorado, a collaborative effort focused on protecting key stream segments in the region. The combination of environmental, recreational and other water user groups initially came together in 2006, and while it’s been a long slog, there have consistently been concrete milestones, keeping Whiting satisfactorily invested. The workgroup hopes to reach some of its big-target goals on legislation to protect the waterways in 2016.

The negotiating landscape continues to change and a promising future beckons. Historically, an “old West” versus “new West” divide in Colorado has periodically crept in to hinder negotiations. Old West is typically characterized by a focus on resource extraction as the key economic base of the community. New West tends to keep a closer eye on conservation.

Some of these tensions must still be navigated at the negotiating table. Bryan, for example, still sees a rural versus urban clash in some situations. In those instances, his advice is to understand that people simply have different approaches and don’t be quick to judge.“Sometimes the way people communicate is a little different,” he says. “In some rural places outsiders are not trusted and perceptions might be different. You need to recognize that if you come from an urban environment.”

Waskom believes members of the younger generations entering Colorado resource management generally bring very open minds to the process.

Bennett agrees: “Younger people coming up in this business are perhaps more open to working together. As the resources get stretched thinner and thinner, younger people want to be part of the solution.”

Smith, too, sees a generational difference: “I see young people coming into the water professions being much more aware about multi-sector collaboration. They’ve caught on that we are not going to solve any problems by fighting.”

Print

Print