The fields of Sterling, Colo., in May are a dependable trio of colors: yellow with the dried remnants of last year’s harvest; the deep brown of freshly tilled earth; and green from new growth. Another hue mars this palette in places, an unwelcome one: white. The color of salt. To crops, it’s the color of death.

There aren’t many patches of dead land. But there are enough to worry farmers and water officials that the same fate that has felled civilizations could befall cities along the South Platte River: that the land will become too salty to support plant life.

“Salinity is always a concern in agriculture,” said Grady O’Brien, a Fort Collins-based hydrologist who has been tapped to lead a study of salinity along the South Platte this year. Colorado Corn, a group representing farmers in the state, is sponsoring the study, with a $39,000 grant from the Colorado Water Conservation Board.

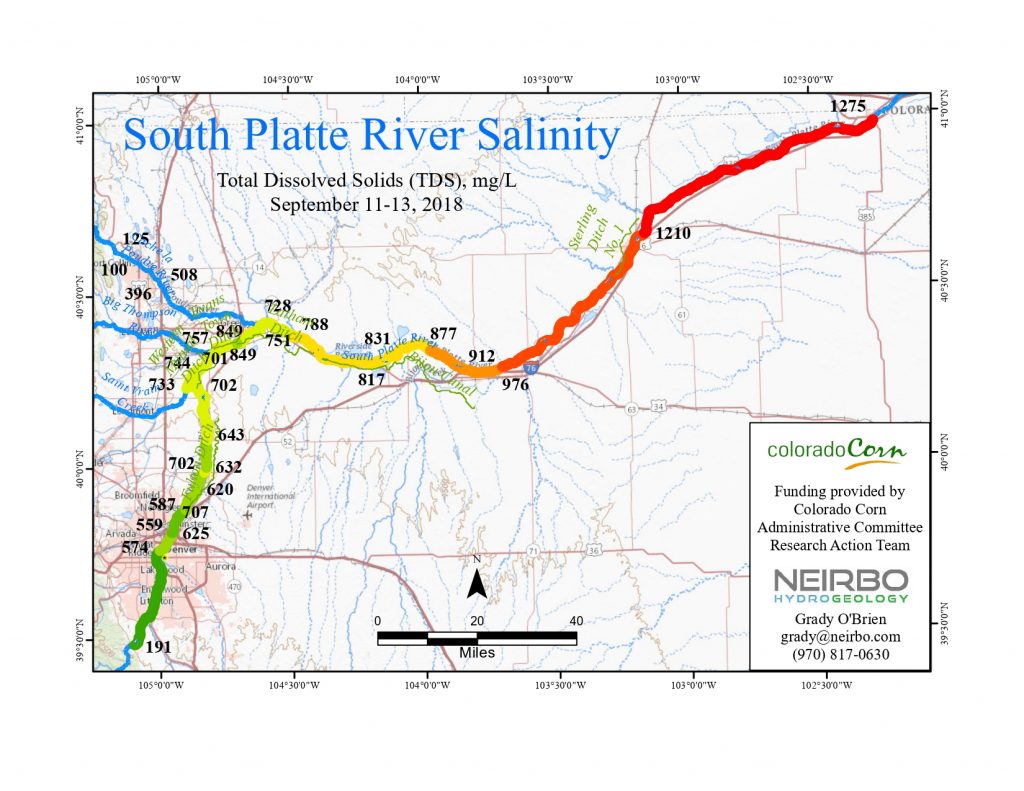

It’s too soon to tell if salinity is a problem on the South Platte. Preliminary sampling by Colorado Corn in September showed worrying signs. Measures were taken at a dozen points along the river from above Denver to the Colorado state line. As the water flowed downstream, its purity dipped noticeably.

Salt is actually a catch-all term for total dissolved solids, or TDS. TDS can include a number of things other than what the general population knows as salt, sodium chloride. In the world of water, “salt” can be magnesium chloride, uranium, selenium — any minerals, salts, metals, and ions that have dissolved in the water.

In samples taken last year near Waterton Canyon, TDS was measured at 191 parts per million. Samples taken near Julesberg, much farther down the river on the Eastern Plains, came in at 1,275 parts per million, according to data provided by O’Brien.

“Once the testing got down around Sterling, it was pretty darn toxic in terms of salt,” said Mark Sponsler, chief executive officer of Colorado Corn. “Those numbers gave us enough of a concern to want to do a more in-depth look.”

The full study will review historical datasets from a handful of organizations, including several water districts, the Colorado Department of Agriculture, and the U.S. Geological Survey. Decades of information should reveal if the South Platte has gotten saltier over time, identify seasonal variations, and uncover potential sources of increased salt.

Salinization is not a new problem; it is as old as civilization itself. What is today Iraq, sometimes called the Cradle of Civilization, was once known as the Fertile Crescent. Centuries of irrigation concentrated salts in the soil to such a degree that nothing would grow.

A study released in early 2018 by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that 37 percent of drainage basins in the United States have been altered by salinity over the past century.

“The greatest threat to irrigated agriculture in the world is salinization,” said Timothy Gates, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Colorado State University. Gates has worked on the Arkansas River, Colorado’s saltiest, for years.

All water, even rainwater, contains salt. When applied to crops (or urban lawns and gardens), plants absorb the water and leave the salts behind, which accumulate over time. In the modern world, agricultural runoff contributes to salinity, as does the increasing use of de-icing compounds on roads.

But it may be in part state water policies that are driving salinization on the South Platte. As drought-prone Colorado focuses on conservation, water is reused more and more. Each use adds a certain amount of salt to the water it pulls from upstream. And while water quality regulations exist for things like uranium, selenium and nitrogen, there are no guidelines for TDS and their effects on agriculture, O’Brien and Gates said.

When Denver gets its water from mountain snowpacks, it is almost as pure as it can be, O’Brien said, at about 100-200 parts per million of TDS. By the time the city pumps treated wastewater back into the South Platte, it’s closer to 500-600 ppm. (Denver Water and the Metro Wastewater Reclamation District declined to confirm TDS levels.)

Downstream of Denver, on its way to Nebraska, the South Platte winds its way past hundreds of miles of roads, farm fields, stockyards, and oil and gas wells. It passes near or through the towns of Brighton, Fort Lupton, Greeley, Fort Morgan, and Brush before it reaches the corn, bean and alfalfa fields of Sterling.

Each city, each wastewater treatment plant, each roadway “keeps adding to that salt load,” O’Brien said. “Salinity is increasing all the way through the basin.”

But Jim McQuarrie, director of strategy and innovation at Metro Wastewater, said wastewater treatment plants can and do improve the quality of the water they treat. For instance, the water Metro puts back into the South Platte has less magnesium and chloride than the water it takes in. “We actually net improve [those] salts.”

McQuarrie said discussions are ongoing about how to improve on all fronts when it comes to salinity: “Wherever there are opportunities for us to avoid unnecessary addition of TDS, we are working on that now.”

By some measures water coming from upstream has improved over the years, said Jim Yahn, manager of the North Sterling Irrigation District. In his region, nitrates from fertilizers used to cause algae and moss growth in rivers and reservoirs, but the problem has dissipated in recent years.

“With increased regulation on municipal effluent,” said Yahn, referencing the outflow that comes from upstream wastewater treatment plants, “the water quality is better in a lot of ways.”

And despite the few crusty patches of field surrounding Sterling, he said farmers aren’t yet worried, though they are looking forward to what the data has to say.

The study is scheduled to be completed in late October.

Correction: Due to an editing error, an earlier version of this story misstated the measurement of TDS.

Shay Castle is a freelance journalist based in Boulder, Colorado. She can be reached at shay.castle6@gmail.com

Fresh Water News is an independent, non-partisan news initiative of Water Education Colorado. WEco is funded by multiple donors. Our editorial policy and donor list can be viewed at wateredco.org.

Print

Print