As ownership of Colorado-Big Thompson water units shifts from agricultural interests to municipal control, farmers in the Longmont and Boulder areas are becoming dependent on the cities’ water rental programs.

And with more municipal control of the Colorado-Big Thompson system, the market has changed in focus from acquisitions to leasing programs for farmers.

Colorado-Big Thompson units can be bought, sold and transferred between water users anywhere within its manager Northern Water’s eight-county region without new uses having to be approved by a state water court, even when a deal involves users in different native stream basins. For that reason, the units have been attractive to those looking to buy in the water market — especially real estate developers needing to dedicate raw water to a municipality or water district to annex in new structures for utility service.

Farmers’ ownership stake shrinks

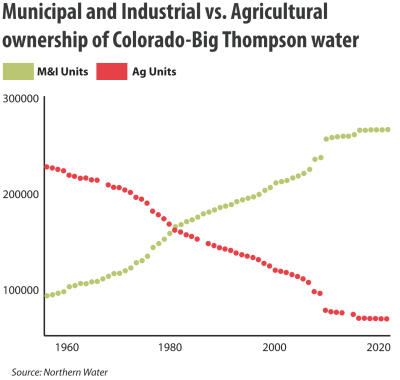

When the Colorado-Big Thompson Project made its first deliveries in 1957, more than 85 percent of its water was owned by agricultural users.

In 2018, though, municipal and industrial ownership of the 310,000 Colorado-Big Thompson water units rose to 70 percent, leaving just 30 percent owned by agricultural users.

But more than half of the system’s water continues to be delivered to farmers, according to Northern Water data.

That discrepancy reflects how much Colorado-Big Thompson water farmers are renting from cities such as Boulder and Longmont.

“Now that the municipal ownership is so high, and the fact that the water is marketable, it’s worth so much to developers, those two factors together cause a situation in which, as we look for agriculture use in the future, [Colorado-Big Thompson] water is increasingly less dependably rented,” Boulder County Agricultural Resources Supervisor Rob Alexander said.

In dry years, municipal users might have less water available to rent to agricultural users and prices are likely to be higher, he said.

“Nearly out of range”

Boulder last year leased out 7,690 acre-feet of water, including 6,950 acre-feet of Colorado-Big Thompson water, and has leased an average of 3,410 acre-feet per year since 2000; Longmont last year leased 612 acre-feet of Colorado-Big Thompson water, along with some city shares of supply ditches that deliver water from native sources such as the St. Vrain River and Left Hand Creek, figures provided by the cities show.

Longmont revenues generated by its water rental program over the last four years total nearly $3.9 million; Boulder, which charges less to lease its C-BT water, has generated $861,850.

“With commodity prices where they are today and the rental value of Colorado-Big Thompson, it’s going to be out of range very soon. It’s nearly out of range now,” Alexander said.

Northern Water in years wet enough to lease excess Colorado-Big Thompson water does so through a bidding system known as its regional pool, and how those bids shake out in the spring influences the overall rental market for water each year.

The minimum successful bid on an acre-foot of water in the spring 2010 regional pool was $22, but last year it was $132, Northern Water spokesman Brian Werner said, a six-fold increase over the decade.

No longer a “go-to” supply

Developers aiming to annex housing into municipalities or water districts that don’t accept cash in lieu of dedicating new raw water units might be forced to look into acquiring shares of ditch companies delivering water from streams native to a city’s or district’s service area.

“We have 10 percent of that ag [Colorado-Big Thompson] supply yet to be transferred” to municipal or industrial control, Werner said, predicting about 20 percent of the system will likely stay under agricultural ownership for the foreseeable future.

“It’s slowed down. About 1 percent a year” is being transferred from ag to municipal and industrial control, Werner said. “Inside the next decade or so, [that system] goes off the table as a go-to water supply.”

Pipe is delivered to the Northern Water’s Southern Water Supply Project, which is under construction north of McIntosh Lake in Longmont. The project, which is expected to be finished in 2020, will deliver water to Boulder, Berthoud, and Left Hand and Longs Peak water districts. (Lewis Geyer / Times-Call Staff Photographer)

Storage may preserve agriculture

With more interest in water markets individualized to native stream basins — as opposed to the trans-basin Colorado-Big Thompson market — applications to state water courts to change ownerships and uses of those native basin shares could pick up, as developers continue trying to satisfy their obligations to give new water to northern Colorado’s growing municipalities.

“We would much rather farm with our native water supply. The reason people want to own [Colorado-Big Thompson water] is because of the investment value,” Northern Water Contracts Manager Sherri Rasmussen said.

Prolonging the time water rights spend on farms could be accomplished by the construction of reservoirs such as the Windy Gap Firming Project or those associated with the Poudre River-based Northern Integrated Supply Project, Longmont Water Resources Manager Ken Huson contends, as they will each store water for a number of municipalities.

“We all wanted viable agricultural communities around our cities,” Huson said, explaining former Longmont Mayor Ralph Price helped conceive the original Windy Gap water storage system in 1967 by filing for Colorado River water rights near Granby so Boulder, Estes Park, Fort Collins, Greeley, Longmont and Loveland could partner on the project.

“That’s why we have open space, because it’s a real part of our community, our culture and what people like around here,” Huson said. “It is what has allowed Longmont to avoid drying up agriculture. The Windy Gap Firming Project will further that.”

The Windy Gap Firming Project is a planned 90,000 acre-foot reservoir that will store water owned by the cities that often goes unclaimed because there is no place to store it when Lake Granby is full. An environmental group, Save the Colorado, has opposed the project with litigation.

“Way of life”

Several Longmont agricultural open space properties are watered with Colorado-Big Thompson units, including some managed by Joe Docheff, who runs the Docheff Dairy business north of Union Reservoir, and who also rents some water from the city for crops on his own land.

“None of these farms anymore, there isn’t enough water attached to them to grow the crops we’re trying to grow,” Docheff said, noting corn and alfalfa are thirsty. “We’re pretty dependent on that leasing program with municipalities.”

Werner predicts even as the Colorado-Big Thompson market continues to be absorbed by the municipal and industrial category, and transfers between uses slow down, there will still be some units available for purchase from agricultural users from time to time.

But Docheff, whose family started farming in Broomfield in the 1930s before moving into the Longmont area 41 years ago, is among those who won’t be selling any of his native or Colorado-Big Thompson water rights.

“The day that our water would be for sale is the day we retire from farming,” Docheff said. “It’s a way of life.”

Added Northern Water’s Rasmussen: “There are going to be farming families that absolutely don’t want to sell [their Colorado-Big Thompson rights.] That’s their golden egg, their supplemental supply.”

Sam Lounsberry: 303-473-1322, slounsberry@prairiemountainmedia.com and twitter.com/samlounz.

This article first appeared in the Longmont Times-Call Jan. 28, 2019.

Fresh Water News is an independent, non-partisan news initiative of Water Education Colorado. WEco is funded by multiple donors. Our editorial policy and donor list can be viewed here.

Print

Print