Groundwater

Most Coloradans associate the state’s water resources with its winter snowpack and flowing rivers, yet beneath Colorado’s surface lie numerous aquifers. From the fractured crystalline rock of the mountains to the vast sedimentary bedrock basins of the Eastern Plains and Western Slope, Colorado’s groundwater resources are a vital piece of the state’s water portfolio.

Groundwater occupies the empty spaces in the soil, sand and rocks beneath our feet. Precipitation is the source of all groundwater, as any rain, snow, sleet or hail that does not evaporate or immediately flow to rivers and streams eventually percolates into the ground.

Groundwater plays a major role in Colorado’s water supply. Nineteen of the state’s 64 counties—and about 20% of the state’s population—rely heavily on well water.

Groundwater use in the state stretches back more than a century. The first documented irrigation well in Colorado was drilled in 1886 northeast of Greeley, and it operated using centrifugal pumps powered by steam engines. Today, the Colorado Division of Water Resources puts the number of groundwater wells statewide at more than 284,000.

%

Portion of groundwater wells in Colorado designated for household use

Of these, 79% are for domestic or household use. Only about 11% serve irrigated agriculture, yet these “high capacity” irrigation wells withdraw the majority of groundwater used in the state—roughly 86% of Colorado’s groundwater is used for agriculture.

It is difficult to pinpoint how many people in Colorado depend on groundwater: U.S. Geological Survey figures suggest that groundwater supplies around 11% of the state’s population, while the Colorado Geological Survey puts that number closer to 20%.

The Groundwater-Surface Water Connection

Groundwater moves along flow paths of varying lengths, depths and travel times from areas of recharge to areas of discharge. Water moves both vertically and laterally within the groundwater system.

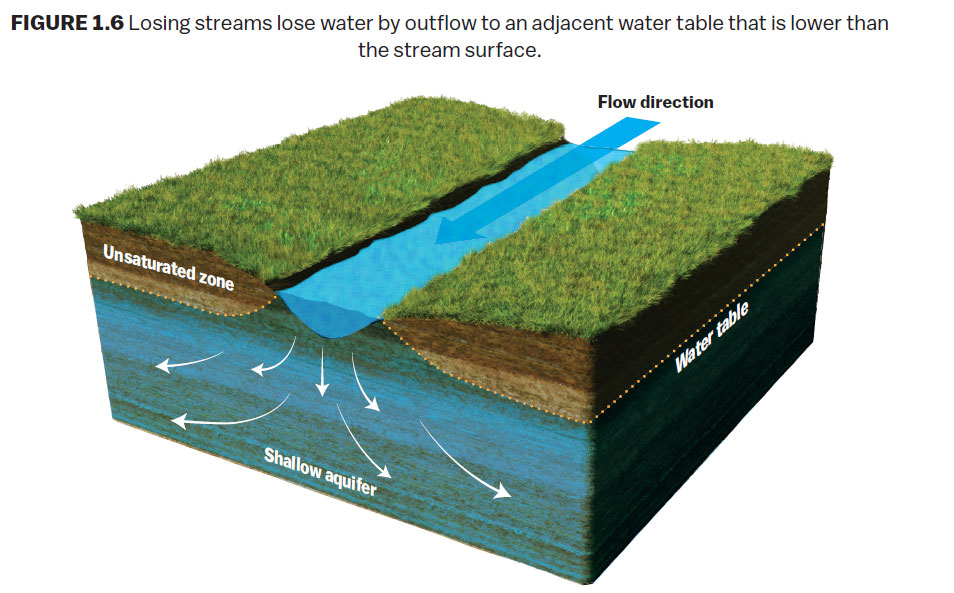

Streams interact with groundwater through their streambed in three basic ways: Streams gain water from inflow of groundwater (gaining stream), they lose water to the aquifer by outflow (losing stream), or they do both depending upon location along the stream’s reach.

For groundwater to discharge into the stream channel, the elevation of the water table in the vicinity of the stream must be higher than the elevation of the stream water surface (Figure 1.5). Conversely, in a losing stream the elevation of the adjacent water table is lower than the elevation of the stream water surface (Figure 1.6).

%

Portion of the world’s freshwater (excluding the polar ice caps) that is groundwater

Water Table

Subsurface water occurs in two zones, the unsaturated zone near the surface and the saturated zone at depth. In the unsaturated zone, the spaces between grains of sediment and cracks within rocks contain both air and water. The upper part of the unsaturated zone is the soil/water zone containing plant roots and animal and worm burrows, all of which enhance infiltration.

Water that is not absorbed by plants or evaporated directly into the atmosphere moves downward by gravity until it reaches a depth where all available space is saturated with water. The top of this saturated zone is called the water table. Below the water table, water pressure is high enough to allow groundwater to flow into wells.

Groundwater can be found almost everywhere, but the water quality and the depth of the water table are highly variable depending on an area’s climate and geology. The water table can be even with the land surface, resulting in springs and seeps, or it can be hundreds of feet deep. Typically, the water table is shallow near permanent bodies of surface water such as streams, lakes and wetlands. The depth and configuration of the water table varies seasonally and annually with changes in the amount, distribution and timing of precipitation.

History & Regulation of Colorado Groundwater

Regulation of Colorado’s groundwater has evolved over time, based on improved understanding of the state’s hydrogeology and an ever-growing water demand fueled by population growth. Drilling a groundwater well didn’t require a permit until 1957, with the passage of the Colorado Ground Water Law. Significant groundwater legislation was passed in 1965 and 1969.

These laws brought tributary groundwater near rivers under the purview of the state’s prior appropriation system, and codified the connection between groundwater and surface water. More recently, in 1995, the state passed the first rules governing aquifer storage and recovery (ASR) for the Denver Basin aquifers. ASR is the practice of pumping treated water into groundwater aquifers for later extraction during dry times.

Questions about the sustainability of Colorado groundwater have long loomed over its use. In some areas, groundwater withdrawals exceed natural recharge rates. Yet solutions to this “groundwater mining” are emerging.

In the agriculturally rich San Luis Valley, for instance, where farmers must either meet their aquifer sustainability goals or face potential curtailment of groundwater diversions, the local water conservation district has devised an innovative system of assessing fees on farmers and using the resulting funds to fallow land. Across the state, from the Denver metro area to Colorado’s Eastern Plains, water users are banding together to bring their water use into balance.

Groundwater Types & Administration

Colorado has four statutory groundwater definitions or classes: tributary, nontributary, not-nontributary (specific to the Denver Basin), and designated groundwater. Tributary groundwater is connected to a natural stream system through either surface or underground flows. All groundwater in Colorado is presumed tributary until determined otherwise by a water court decree, issuance of a well permit, or determination by rule.

Nontributary water is disconnected from surface water due to geologic conditions

such as faulting, confining layers, or great distances. The legal standard for nontributary water is that pumping will not, within 100 years of continuous withdrawal, deplete the flow of a natural stream at an annual rate greater than one-tenth of one percent of the annual rate of withdrawal. Nontributary groundwater may be used without developing a plan for replacing depletions to the surface water system, such as an augmentation plan or replacement plan.

Non-Tributary Denver Basin Groundwater

Within the Denver Basin are multiple sedimentary bedrock aquifers situated one on top of the other in layers, like a stack of shallow bowls. Between each aquifer is a confining layer that separates the individual aquifers and the water stored in each of them. Due to the nature of the confining layers and because of the limited connection between these aquifers and surface water, the groundwater in the aquifers is only directly recharged by precipitation along the basin edges where they outcrop.

Nontributary areas in the Denver Basin are mapped in the Denver Basin Rules, which govern the withdrawal of groundwater from the Denver Basin aquifers. Aquifers in the Denver Basin that are not mapped as nontributary are termed not-nontributary. The pumping from those aquifers has an impact on nearby stream systems, although over a longer time span than pumping from tributary aquifers. Those potential impacts are handled differently per the Denver Basin Rules.

Designated Groundwater Basins

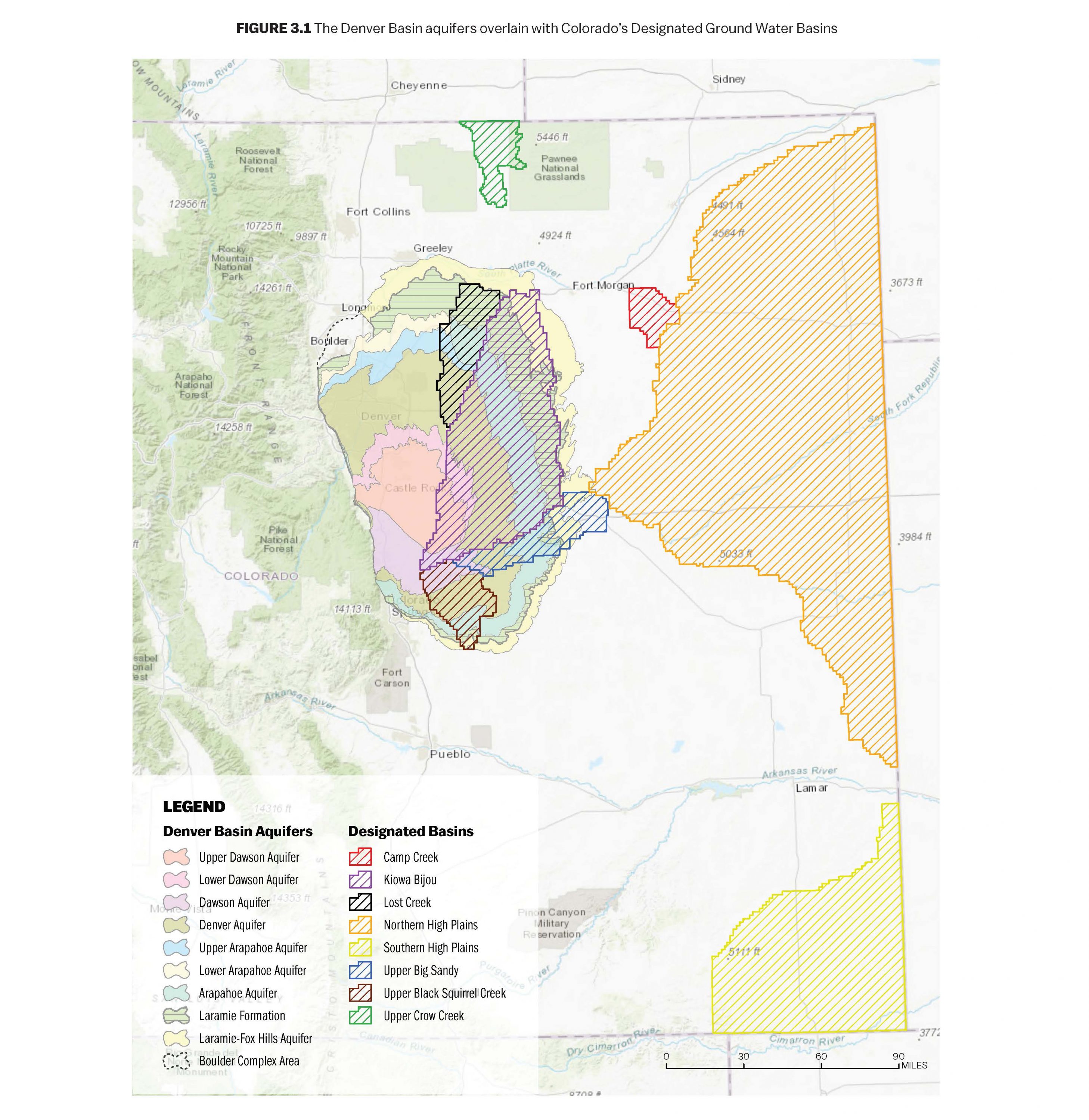

There are eight regions in eastern Colorado termed Designated Ground Water Basins (Figure 3.1). Designated Basins are established when the Colorado Ground Water Commission determines that the groundwater they contain is either not required for the fulfillment of decreed surface rights or is in an area not adjacent to a stream wherein groundwater withdrawals have constituted the principal water source for at least 15 years.

Designated Basins encompass alluvial and bedrock aquifers, parts of the Denver Basin aquifers, and the High Plains aquifer. Designated groundwater is administered under a separate legal regime from other waters of the state, with the Ground Water Commission having administrative authority rather than the state’s water courts. There are 13 locally controlled Ground Water Management Districts within the Designated Basins, which have some additional authority to administer groundwater within their boundaries.

Groundwater & Prior Appropriation

All new wells drilled in Colorado are required to have a well permit issued by the Division of Water Resources. This provision was originally outlined in the Colorado Ground Water Law, also known as the 1957 Act.

Wells are administered within the prior appropriation system unless they are nontributary or exempt. This process of incorporating groundwater development into the legal system governing surface water was outlined 50 years ago in a landmark bill, the Water Rights Determination and Administration Act of 1969 (the 1969 Act).

The 1969 Act created seven water divisions across Colorado and corresponding division engineers and water courts for each of them. In order to promote the use of groundwater and increase the available supply of water for beneficial use, the law established augmentation plans. Well users could file a water right to use their tributary well, but most wells would still be junior to surface water rights.

An augmentation plan allows a well user to replace (augment) the depletions to the local stream system caused by pumping a tributary well so that they can pump even when they are out of priority. These plans must be approved in the local water court and must show how, when and where an applicant will replace their well depletions.

Replacement sources for augmentation plans can be any legally available water source, including nontributary groundwater, water stored in a reservoir, or water infiltrated to the underlying aquifer through a recharge pond. Wells that pump nontributary groundwater are not administered under the prior appropriation system but are still regulated by the Division of Water Resources.

Groundwater Supply & Demand

Exactly how much groundwater does Colorado have? A comprehensive assessment of Colorado’s groundwater resources has never been conducted. Yet the variety of its aquifers and the predominance of surface water use suggests that this resource is underdeveloped in some areas.

Colorado’s groundwater resources are significant. In 2003, the Colorado Geological Survey (CGS) conducted a statewide assessment of underground water storage options. A byproduct of this evaluation was a quantification of the existing water stored in the alluvial groundwater reservoirs, which was estimated to be over 37 million acre-feet.

The magnitude of this quantity of water is better understood when considering that Colorado’s total surface water reservoir storage capacity is approximately 7.5 million acre-feet within 1,953 reservoirs. The estimated recoverable groundwater reserves in the Denver Basin aquifer system alone are 200-300 million acre-feet, or some 35 times more than all the surface reservoir water storage in the state.

35x

The estimated recoverable groundwater reserves in the Denver Basin aquifer system is some 35 times more than all the surface reservoir water storage in the state

Depth, Yield & Quality

Development of groundwater resources is constrained by economic considerations related to the depth of the resource, productivity or well yield, and water quality. While wells completed in alluvial aquifers tend to be shallow and therefore less expensive, those in bedrock aquifers can be 1,000-feet deep or more. Municipal water supply wells rarely exceed 2,500 feet in depth, as the cost to produce that water becomes prohibitive.

While individual water districts and municipalities in Colorado keep track of their water uses, the State of Colorado does not compile groundwater use data. The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), however, publishes the Estimated Use of Water in the United States report on a five-year interval. The USGS 2015 report indicates that for that year, total water withdrawals in Colorado were 11.5 million acre-feet. Of that total, 1.68 million acre-feet, or 14.6%, was groundwater.

The USGS water use report identifies water withdrawals by principal uses such as public supply, domestic, agricultural, industrial, mining, and thermoelectric power. As with surface water, the dominant use of groundwater in Colorado in 2015 (86.9%) was for agricultural irrigation. Public water supply was the next highest use, comprising 7.26% of total withdrawals by public and private water suppliers. Slightly over 8% of Colorado’s population is served by public water suppliers withdrawing groundwater. Considering those residents self-supplied by wells, groundwater supplies 19% of the state’s current population.

Based on the USGS 2015 water use data, of the 64 counties in Colorado, groundwater supplies less than 10% of total water use in 36 of them. At the other end of the spectrum, eight counties, all in eastern Colorado, rely on groundwater for 80% or more of their total water supply, and 12 counties (mostly located on the Eastern Plains) rely on groundwater for at least 50% of their supply.

When groundwater withdrawals exceed an aquifer’s natural rate of recharge, this is called a “mining” condition. Groundwater mining results in declining water levels and loss of water in storage. Mining conditions exist in some areas of the state with a high density of irrigation wells or high-capacity municipal wells. A mining condition has not been documented in aquifers where withdrawals are dominated by exempt domestic water supply wells.