This four-part series contrasts the processes behind the Colorado Water Plan with four other recent Western water plans: California, Texas, Montana and Oregon.

by Hannah O’Neill, Bianca Valdez and Jakki Davison

State water plans account for contemporary water resource challenges, detail supply projections and future demands, and catalyze community discussions around cooperative management. How does the Colorado Water Plan—both the final document and the planning processes involved—compare to other Western states?

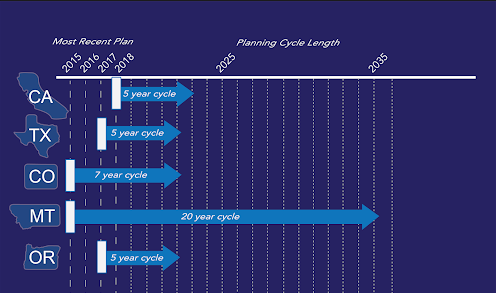

As we approach the second iteration of the Colorado Water Plan (set to begin in 2020, per the schedule outlined in the 2015 water plan), this blog series will explore a diversity of water planning processes. There are currently 17 U.S. states with water plans. Here, we explore five Western state plans that were all published in the last five years: Colorado, Oregon, Montana, Texas and California.

What’s in a water plan?

State water plans identify current water demands, project future water supply, and explore potential water projects that will close the gap between projections of future needs and availability. Every state water plan is unique and is largely rooted in the political context of an individual state. Creating a state water plan involves an enormous amount of stakeholder engagement and number crunching in order to understand statewide trends in population, climate and hydrology; articulate state and regional values with regards to water consumption and diversion; and identify both broad regional goals and local water projects to meet those goals.

Unique Western states; unique water resource challenges

Importantly, the states featured in this blog series represent two different legal frameworks in how water rights are administered: Colorado, Oregon and Montana operate under prior appropriation, while Texas and California operate under a dual regime of riparian rights and prior appropriation. Prior appropriation, or “first in time, first in right,” allocates water based on the chronology of water diversions for “beneficial use,” or the public good. In contrast to prior appropriation, riparian rights governance associates the ownership of water rights with the ownership of land adjacent to water bodies. Proposed water policies and projects are fundamentally shaped by how water rights are defined; in this manner, the legal framework within a given state provides essential context for how planning processes are applied.

Each state planning process is informed by the state’s unique combination of legal doctrine of water governance, history of water planning and development, and current statewide priorities. Every state is working to meet unique planning and regulatory requirements in the implementation of water projects and programs; the discussion of differences within this blog series is not intended to imply differences in plan quality. Like any good policy, the water plans reviewed here all aim to keep pace with emergent environmental, social and fiscal needs.

In the following three blog posts, we will contrast distinguishing components of these five Western water plans in order to better understand the planning process in Colorado. The focus of our discussion will contrast various strategies for executing regional engagement, modeling future scenarios, and incorporating uncertainty; all across our five states of interest: Colorado, Texas, Montana, Oregon and California.

Read our full Western Water Plans series with posts:

Read our full Western Water Plans series with posts:

“How does the Colorado Water Plan compare to our neighbors”

“How do Western states incorporate regional engagement into water resource planning”

“Uncertain about uncertainty”

“How do Western states plan for uncertain futures in water policy”

This series was developed by Hannah O’Neill, Bianca Valdez, and Jakki Davison, three graduate students studying environmental policy at the University of Colorado at Boulder’s Masters of the Environment program.

Print

Print